Book review: ‘The Old Straight Track’ by Alfred Watkins

Quite possibly my favourite book of all time… I’ve been meaning to review this for so long!

When Alfred Watkins was riding around the Herefordshire hills in the early 1920s, he pulled up his horse to gaze across the landscape, and he had a sudden revelation.

When Alfred Watkins was riding around the Herefordshire hills in the early 1920s, he pulled up his horse to gaze across the landscape, and he had a sudden revelation.

In his vision, every landmark, whether natural or man-made, was linked by a network of straight lines, which he saw as glowing wires laid out over the surface of the land. The lines passed through hill summits and cairns, linking church spires, prehistoric settlements and burial sites, old encampments and sacred monuments. Following the route that they took were trackways, straight roads that had been ancient and well trodden long before the coming of the Romans, along which the first settlers of this country would have travelled by day and night, their eyes keenly aware of waymarkers that we, in our age of all-seeing technology, are now almost blind to.

Although the name didn’t come to him in that instant, Watkins called these tracks ‘ley lines’.

A keen amateur archaeologist, Watkins was spurred into action, studying maps and undertaking many months of research in the field. This was his native country, and he already knew it like the back of his hand; he soon discovered countless alignments, far more than could conceivably exist through coincidence alone.

Watkins revealed his theory in an address to the Woolhope Club, an amateur archaeological society in Hereford, of which he was a member. He followed it up with an essay entitled ‘Early British Trackways’ and then, in 1925, with a book called ‘The Old Straight Track – its Mounds, Beacons, Moats, Sites and Mark Stones’.

There are few books which truly merit the word ‘iconic’, but in my opinion, ‘The Old Straight Track’ is one of them. Nearly 90 years after its publication, it continues to open the eyes of readers so that they see the landscape in an entirely new light; as John Michell rightly puts it, writing in the Foreword, for many people the book “awoke, as it were, the memory of a half familiar truth.” When I first read the book for myself, getting on for 20 years ago now, this was certainly my own experience.

There are few books which truly merit the word ‘iconic’, but in my opinion, ‘The Old Straight Track’ is one of them. Nearly 90 years after its publication, it continues to open the eyes of readers so that they see the landscape in an entirely new light; as John Michell rightly puts it, writing in the Foreword, for many people the book “awoke, as it were, the memory of a half familiar truth.” When I first read the book for myself, getting on for 20 years ago now, this was certainly my own experience.

Not that Watkins’ theories were greeted with widespread acclaim – far from it, in fact. Few people took his ideas seriously, and he became the subject of ridicule. This was an age that wouldn’t tolerate alternative interpretations of history, and the horrified reaction of many traditional historians probably masked an underlying instinct of fear.

But let’s not dwell on them! Watkins might have been a little hazy about time periods, as modern archaeologists have pointed out, but he was writing long before the advent of radiocarbon dating. In his descriptions, it’s easy to hear the voice of a man so in tune with the countryside, so observant and appreciative of the heritage that he was exploring.

Introducing the concept of ley lines, Watkins paints an irresistible picture of rural bliss:

“The outdoor man, away on a cross-country tramp, taking in the uplands, lingering over his midday sandwich on the earthwork of some hill-top camp, will look all round ‘to get the lay of the land.’”

And sometimes his descriptions are flavoured by his job as a travelling representative for his family’s brewery business:

“The air – playing down from the Forest – is like wine all over Radnor Bottom, and folk from the more relaxing plains of Herefordshire come for a brace-up to quarters such as ‘The Eagle’ or ‘King’s Arms’ at New Radnor…”

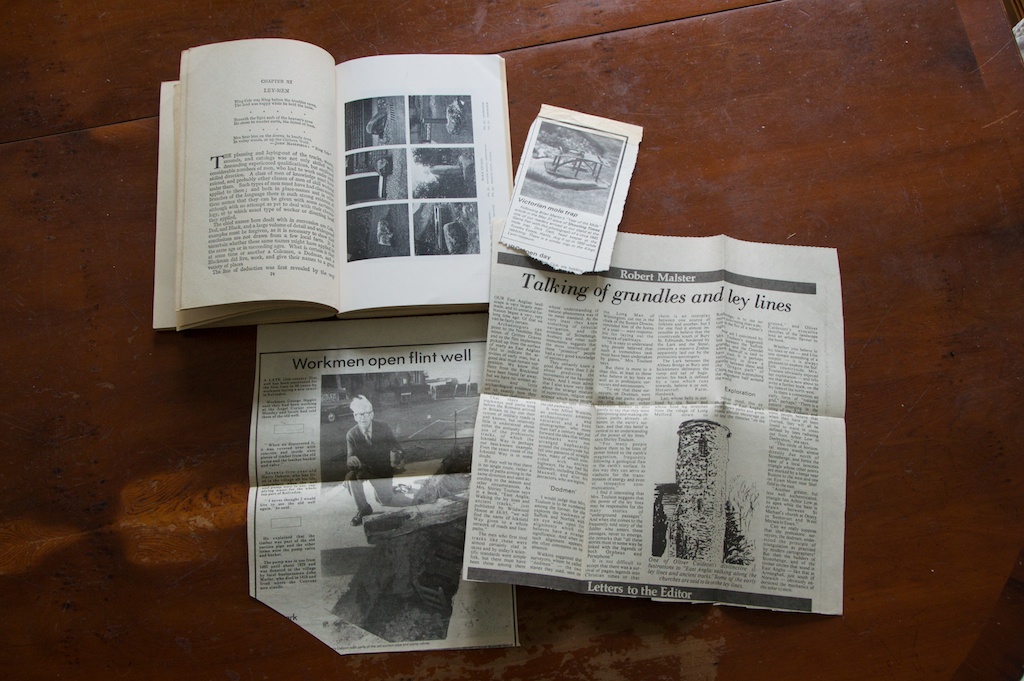

He goes on to describe the construction of ancient mounds, many of which have now been lost through agriculture and development, but which would have served as sighting points along ley lines; he looks at ‘mark stones’, ancient monuments ranging from standing stones to the remnants of wayside crosses, some of which were inscribed with grooves running down their length, which intrigued him enough to try inserting a broomstick into them, to see if they were designed to hold an early theodolite or surveyor’s pole; and water sight points, either natural fords in rivers, or man-made moats or ‘flashes’.

And he then adds a fascinating third dimension in the form of word derivation and place names: in England a ‘flash’ is a regional term for a pool, but of course it is also a sudden burst of light; the word ‘moat’ can also be spelled ‘mote’, meaning a tiny speck that catches the sunlight; and ‘ey’ (which you can’t help but link with ‘eye’) is an old name for an island. Were moats and flashes originally seen as way markers, reflecting the sun (or moon) light when viewed from a certain point on a path, reassuring a traveller that he was on the right track? Were they designed to mirror the night-time flames of a distant beacon?

Watkins examines place names with elements of ‘cole’, ‘coal’ and ‘coel’; those containing ‘black’, also found in ‘blache’ and ‘blake’; and ‘dod’, ‘tot’ and ‘tut’ (in Welsh, ‘twt’), which are found in names such as Doddington, Dodderhill, Totnes and Toothill.

About the ‘cole’ names and their variants, which are far too ancient and widespread to derive from any coal-mining activities, Watkins gives archaic definitions of ‘coel’ which referred to omens and divination, and cites the old term ‘cole-prophet’ to describe a wizard or sorcerer. Following this train of thought, he suggests a long-lost practice that has left our landscape littered with names like Coleshill, Colebatch, Colebrook and many ‘cold’ variants like Cold Ash, Coldborough and Cold Harbour. He says:

“The general conclusion is that the Coleman, who gave his name to all kinds of points and places on the tracks, was a head-man in making them, and probably worked from the Colehills, using beacon fire for marking out the ley.”

When you find yourself suddenly enlightened about place names close to your own roots – in my case, Cold Hatton in Shropshire – you do almost literally ‘see the light’.

The same theory is applied to ‘black‘ or ‘blake‘ (which, intriguingly, Watkins also allies with ‘bleach‘ and ‘bleak’). This has little to do with our modern understanding of ‘black’, but may instead have referred to a gleaming light. And as for the ‘dod‘, ‘tot’ or ‘toot‘ hills, he suggests that they preserve the memory of the ‘dodman’, the man who worked with two long rods, moving them back and forth while keeping a number of distant landmarks in sight, ensuring that sighting mounds and stones were erected in precisely the right points along a track.

Pondering the old folk name of ‘dodman‘ to describe a garden snail, used by Charles Dickens in ‘David Copperfield’, Watkins matter-of-factly recounts another of his lightbulb moments:

“The sight of a snail out for a walk one warm moist morning solved the problem. He carries on his head the dod-man’s implements, the two sighting staves.”

Although the hilltop forts, churches, castles and mark stones provide the substance, for me it is the old words that form the star around which Watkins weaves his golden web of magic – and it really is magic, because I have found myself drawn back in, once again feeling the hairs rising on the back of my neck, just from re-reading his chapter on place names and knowing – just knowing, somewhere in the very back of my mind – that he has stumbled on a very deep and ancient truth.

With our modern mindset we might take issue with Watkins’ interpretation of his discoveries… but I feel that sometimes we approach history with too much science and not enough instinct, overlaying an almost-forgotten intuition with an ever-growing reliance on statistics and computer analysis. What Watkins did was go back to the land, and speak to the old folks (who have now long since gone, and their families probably moved away); he allowed himself to see and listen with his heart, and he wasn’t afraid to smash the china urns of accepted knowledge. He was a true visionary, and I would love to have talked to him – better still, walked with him along some of the ridges that he knew so well.

‘The Old Straight Track’ is a snapshot of a countryside that has now changed probably beyond Watkins’ recognition; it’s a humbly-written explanation of an idea that is as revolutionary as it is brilliant; and it’s a bottomless mine of gems, little nuggets of enlightenment that make you feel that you’re the first to discover them. There are so many more I could tell you about, but I don’t want to spoil the pleasure!

I realise that ley lines might be verging too far into the ‘hippy dippy’ side of history for some people, and in that case this book probably isn’t for you. But if you are willing to entertain an idea that might have more than a grain of truth in it, I can only recommend that you buy yourself a copy, and allow yourself the time to read and enjoy it. And if you’ve already read it, you will know for sure what I’m talking about, and I’m willing to bet it’s one of your most treasured books.

I realise that ley lines might be verging too far into the ‘hippy dippy’ side of history for some people, and in that case this book probably isn’t for you. But if you are willing to entertain an idea that might have more than a grain of truth in it, I can only recommend that you buy yourself a copy, and allow yourself the time to read and enjoy it. And if you’ve already read it, you will know for sure what I’m talking about, and I’m willing to bet it’s one of your most treasured books.

My own copy, which was purchased second-hand, also contains loose newspaper cuttings from the 1970s about ley lines in East Anglia and one about a Victorian mole trap that someone had dug up while out rabbiting. Who could ask for more? If I had to save just one book from my bookshelf I’d be distressed, but I’d choose this one.

Ley hunters…

Although it was initially greeted with derision, Watkins’ ley line theory gained enough followers during his lifetime for him to establish a society called The Old Straight Track Club, which he actively participated in until his death in 1935 at the age of 80. The papers of the Club are in Hereford’s city museum.

Watkins also unknowingly lit the fire of a widespread passion for ley hunting that was seized on again in the 1960s and 70s, and whose flames show no signs of going out. Ancient tracks, energy lines of the earth, angel pathways… however ley lines are interpreted, the concept has a fresh appeal for each successive generation, and that in itself is perhaps a sign that it holds some fundamental truth – and we acknowledge it with an awareness which goes much deeper than logic.

Who was Alfred Watkins?

Born in 1855 to a wealthy family who owned a flour mill and a brewery, Alfred Watkins was a man ahead of his time. Quite apart from his revelations about ley lines, he was a keen bee-keeper, a member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society. He invented the Watkins Bee Meter, an ingenious exposure meter the size of a pocket watch, for use with plate cameras. If you love vintage photo equipment, take a look on eBay – good examples sometimes come up for sale!

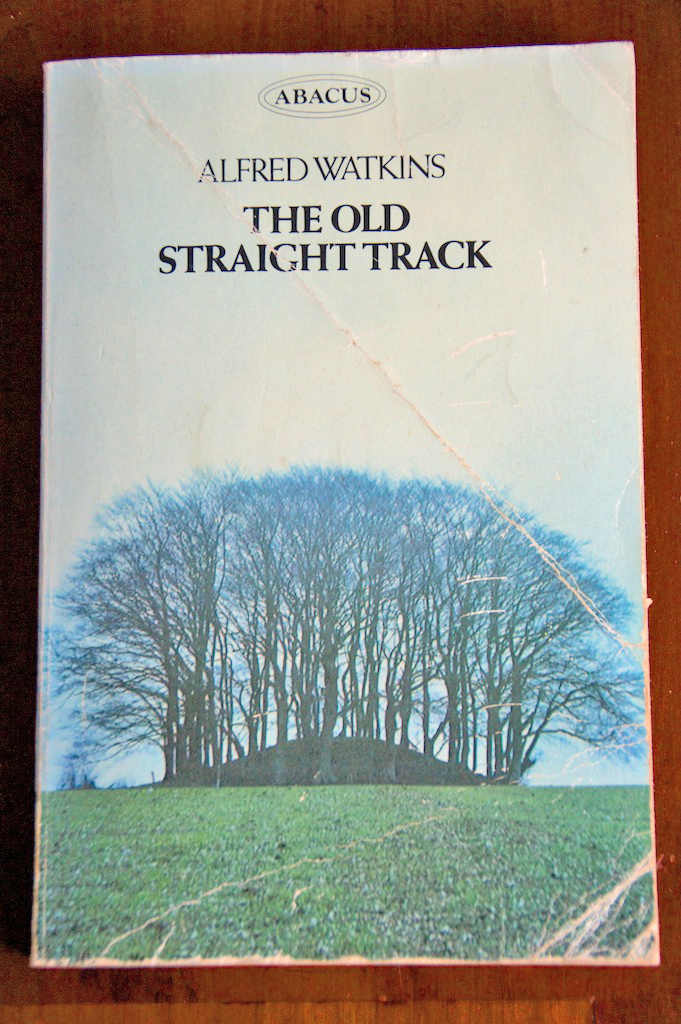

‘The Old Straight Track – Its Mounds, Beacons, Moats, Sites and Mark Stones’ was first published in 1925. After several re-prints it’s now available from Abacus, ISBN 978-0349137070, RRP £14.99 (paperback, 240 pages).

My thanks to Shane who writes a blog called The Biggest Little Hills, for his kind permission to reproduce his photos of Bromlow Callow in Shropshire.