The Stone of Scone

The Stone of Scone, otherwise known as the Stone of Destiny, has so many legends and stories about its origin that it’s hard to know where to start.

In 1296, four years after the coronation of John Balliol as King of Scotland, the Scots were defeated by the English at the Battle of Dunbar. King Edward I, the ‘Hammer of the Scots’, continued to make rapid progress through Scotland, taking possession of its principal castles and religious centres, which included Scone Abbey. Aware of the history and symbolism of the Stone of Scone, he lost no time in despatching it to England, along with the Scottish ‘Honours’ or crown jewels and St Margaret’s holy rood.

Meanwhile King John was taken prisoner, and the Great Seal of Scotland was smashed. In a public display of humiliation usually reserved for knights who had committed treason, the Bishop of Durham stripped the red and gold royal arms from John’s surcoat; he was then taken to the Tower of London. John’s abiding nickname, ‘toom tabard’, or ‘empty cloak’, is a reminder of his fate and it also sums up national opinion of him at the time.

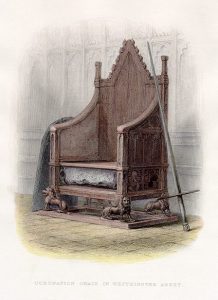

The Stone of Scone in the Coronation Chair at Westminster Abbey (‘A History of England’, 1855)

Once the Stone was in England, Edward gave it into the care of the Abbot of Westminster, and had a Coronation Chair specially designed to contain the Stone in its base, where it remained for the next 700 years. Apparently, until the return of the Stone to Scotland in 1996, the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey was the oldest piece of furniture in England which was still used for its original purpose.

But was it the real thing?

There are some historians, however, who doubt that the lump of sandstone which Edward seized as the ultimate Scottish souvenir was actually the real one. According to one source, Edward I sent a raiding party back to Scone Abbey in 1298, in search of something – but whatever it was, they returned empty-handed. If the monks of Scone had swapped the precious Stone of Destiny for a fake, they had hidden the real one very well.

Interestingly, Edward III offered to return the Stone three times: at the Treaty of Northampton in 1328, which recognised Scotland as an independent nation following the victory of Bannockburn; a year later, in 1329; and finally in 1363. If the Stone was the real one, some historians argue, why did the Scots not accept it back? Was the original Stone buried in some remote, misty hillside?

According to one tale, sometime in the late 18th or early 19th century, two farm lads went to investigate a landslide near Scone. They discovered that it had exposed a narrow fissure in a rock, and, looking through it, they could see an underground chamber, part-filled with debris. In the centre of the chamber was a carved stone, raised off the ground on four pillars.

The lads thought no more of it at the time (this fact alone makes me a little sceptical!) but a few years later one of them heard the story of the Stone of Scone and wondered if they had stumbled across it. On returning to the hillside, he was unable to locate the hole in the rock; perhaps it had been hidden by another landslide or fresh undergrowth.

Replica of the Stone of Scone at Moot Hill, Scone

And then there’s the equally puzzling story of Ireland’s own ‘Stone of Destiny’. Legend tells how this stone was used as a pillow by Jacob in Biblical times, and was carried by refugees fleeing from persecution in Jerusalem. Among these refugees was a princess known as Tea or Scota. They fled through Egypt, Sicily and Spain, and finally arrived in Ireland, where the stone became known as Lia Fáil or the ‘Stone of Destiny’. It was used as the coronation stone of Ireland’s high kings, and was said to cry out in joy when the rightful king of Ireland touched it.

A stone known as the Lia Fáil stands on the Hill of Tara in County Meath, the ancient seat of Ireland’s kings. But according to some accounts, the true Lia Fáil (or maybe a piece of it) was carried to Scotland in the early 6th century and used in inauguration ceremonies of the kings of Dalriada. When Dalriada was absorbed into the wider kingdom of Alba, the stone was moved to Dunkeld… but an alternative story claims that it was carefully hidden in a safe place, such as Dunstaffnage, just north of Oban. The writer and historian Nigel Tranter believes that Robert the Bruce gave the real stone into the custody of Angus Og MacDonald, Lord of the Isles, who hid it on the Isle of Skye.

Dunstaffnage Castle

So, is the Stone of Scone the real Stone of Destiny? We may never know. The stone that sits in Edinburgh Castle is hewn from red sandstone, which can be traced to the Scone area. The monks may have had a replica created… or, faced with an impatient English monarch, they may have cast about for any ready-made oblong boulder that was to hand. One story even suggests that they used the stone lid of the royal cesspit!

Edinburgh Castle, now the home of the Honours of Scotland and the Stone of Destiny

Stealing the stone back to Scotland

Whatever its provenance, the Stone that was seized by Edward I and taken back to London remained in its custom-made position, underneath the Coronation Chair, until Christmas Day 1950. On that morning, four Scottish students, intent on doing their bit for Scottish independence, staged an outrageously daring heist in the style of The Italian Job.

One of them, Ian Hamilton, had found out that the easiest way into the Abbey was via a side door which was made of pine – more yielding than heavy oak. They gained access with a crowbar, and while one of them waited in a get-away car, the others tugged at the Stone in an attempt to free it from the Chair. It was so heavy that it toppled and broke into two pieces… but, Hamilton recalls, this made it easier to carry.

With a night watchman already raising the alarm, the four made a dash for Scotland, and reached the border without being apprehended. They left behind them a city in uproar, and an extensive police search proved fruitless. Although the students were questioned, they were never charged.

After a year, Ian Hamilton yielded and left the Stone at Arbroath Abbey – fittingly, the site of the Declaration of Arbroath, a statement of Scottish independence submitted to Pope John XXII in 1320. But there was a rumour, which still persists, that a replica had been made of the Stone when it was repaired and fixed back into one piece by a Glasgow stonemason – and that it was a copy, rather than the original, which was returned to England.

Ian Hamilton went on to forge a successful career as a lawyer, eventually becoming a QC. In an interview which he gave to the Daily Telegraph in 2008, he said he felt no regret about ‘stealing’ the Stone and bringing it back to its homeland – in fact, he was proud. He added: “I felt I was holding Scotland’s soul when I touched it for the first time.”

A shared heritage

The Stone was restored to Westminster Abbey, where it lay under the throne for the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. However, in 1996 the Stone was returned to Scotland, on condition that it would be sent back to London to play its part in subsequent coronations. On 6th June 2023 it will sit under the Coronation chair of HM King Charles III.

Some people still believe that the Stone of Destiny in Edinburgh Castle is a 13th century fake, created by resourceful monks at Scone. Ian Hamilton, who wrote a book called ‘The Stone of Destiny’, was convinced that it is the real thing.

Who knows? Only the Stone itself! But if it isn’t, wouldn’t it be wonderful to find the original?

St Edward’s Chair without the Stone of Scone

Sources:

- Ian Hamilton, ‘The Stone of Destiny’, 2008 (first pub. 1952 as ‘No Stone Unturned’)

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Scone Palace

- English Monarchs

- Westminster Abbey

Images from public domain except Dunstaffnage Castle and Edinburgh Castle which are copyright Jo Woolf