The Palace of Holyroodhouse

The glass case was full of the most exquisite treasures: miniature portraits, little silver toothpicks, brooches and rings and small duelling pistols and locks of hair. I bent and studied them for a while and then, standing up and drawing breath, I noticed a full-size painting hanging in an alcove: a young man in a fine lace collar and cuffs, dark-haired, with a fashionable moustache and goatee beard, holding a stringed instrument in his hands. His expression is relaxed and quite candid, as if he’s idly pondering what tune to play next.

I walked over to take a closer look; and then, glancing down, I saw the red stain on the floorboards.

“I went also to see Mary Queen of Scots’ Bedchamber (a very small one it is) from whence David Rizzio was drag’d out and stab’d in the ante room where there is some of his Blood which they can’t get wash’d out.”

The future Duchess of Northumberland, writing in 1760 and quoted in the official guide to the Palace of Holyroodhouse

I’m not the first visitor to Holyroodhouse to stare in morbid interest at the apparently unmovable stain on the spot where David Rizzio, secretary and favourite of Mary Queen of Scots, was stabbed in cold blood; but the stain itself has had an interesting history over the years, appearing in one report as dark brown, and in another as rust-coloured; while in his ‘Chronicles of the Canongate’, Sir Walter Scott recounts a probably fictitious but delightfully entertaining story about an over-enthusiastic detergent salesman who horrified a caretaker by getting down on his hands and knees with a scrubbing brush:

“Two hundred and fifty years, ma’am, and nothing take it away? Why, if it had been five hundred, I have something in my pocket will fetch it out in five minutes.”

We visited the Palace of Holyroodhouse in early January, on a day of low cloud and occasional hints of blue sky that were as fleeting as they were precious. In terms of the tourist season, this was the quietest it could get: the Christmas crowds had gone, and the weather had probably driven most sane people to the Bahamas. So we felt almost as if we were the only visitors when we walked through the ornate archway into the quadrangle and then turned right, through a door into an entrance hall and up the Great Stair.

The Quadrangle. Photography is prohibited within the Palace itself

The Quadrangle. Photography is prohibited within the Palace itself

Along the landing, a door was open into the Royal Dining Room, where a highly polished table was gleaming with crystal and silver. This banqueting service, comprising over 3,000 pieces and designed to serve 100 guests, was presented to George V and Queen Mary in 1935, to mark their silver jubilee. A custodian was tenderly polishing one of the tureens, in an atmosphere of almost reverential silence. I could just imagine Carson, Downton Abbey’s strait-laced old butler, purring with pleasure.

Another door opened onto the Throne Room, slightly oppressive with oak panelling and a deep red carpet, and almost bare of furniture except for two matching thrones with loads of embroidery and tassels and the initials ‘GR’ and ‘MR’, representing George and Mary. Eyeing us suspiciously from over the fireplace was a portrait of James VI, dressed in sober black with a white frill at his throat; I remembered the guide at Drumlanrig Castle telling us that James always had his clothes padded with horsehair, because he was so fearful of being stabbed. I can only feel sorry for him. And for his wife, actually.

The Evening Drawing Room, the Morning Drawing Room… each clad in wall-size tapestries, garnished with wedding-cake ceilings of impossible plasterwork. Then the King’s Bedchamber, designed for Charles II, with the state bed draped in red damask, and plenty of elaborate walnut furniture. By this time I was beginning to feel like you do when you’ve eaten too many chocolate liqueurs, and so I was quite relieved to emerge into a huge long room called the Great Gallery, again practically devoid of furniture but adorned with portraits by Jacob de Wet of every single king of Scotland from the earliest times to the reign of Charles II. Some of these – for example Macbeth, Fergus I and Robert the Bruce – owe a great deal to the artist’s imagination, but he obviously put a huge amount of energy and character into his creations. You can almost imagine Charles II wandering along here at night, his chestnut curls bouncing, gazing with pride at his illustrious ancestors. And what a setting it made for his great-nephew, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, who held a glittering ball here in 1745, to celebrate his arrival in Edinburgh at the height of the Jacobite rebellion.

Forgotten queens: Regardless of the era, I always wonder what the women – royal princesses and would-be queens – made of all the splendour. Some of them were accustomed to it, no doubt, and perhaps even expected it; but most of them were young and inexperienced, ill at ease in a foreign country, their youthful spirit walled up in a dark and claustrophobic palace with ghosts at every turn.

One of the queens who had every reason to blanch at shadows was Mary, Queen of Scots. She was certainly born into the grandeur, inheriting the throne at six days old and fulfilling her father’s deathbed prophecy that the crown of Scotland would ‘gang wi’ a lass’. But the Stewart kings, from James the First to the Fifth, didn’t have much of a track record for happiness or good fortune, and Mary seemed to have inherited all their worst tendencies.

“Although, in many respects, a brilliant and distinguished race, the sad fate which overtook most of the Stewart occupants of the Scottish throne forms a chronicle of disaster without parallel in the history of any other royal family in Europe.”

‘Holyrood, its Palace and its Abbey – an Historical Appreciation’ by William Moir Bruce

The Old Royal Apartments in James V’s Tower

James V’s Tower is the oldest surviving part of Holyroodhouse, and as you step into the rooms here the atmosphere changes, slightly but perceptibly. When you climb the winding stone stair up to the second floor, emerging into a room of smaller proportions but with a heavy air about it, you suddenly realise where you’re standing. This is the bedchamber of Mary, Queen of Scots: the initials carved on the oak ceiling are those of her parents, James V and Mary of Guise; the frieze around the walls (now faded to grey) was designed to mark her arrival at the Palace; and the tiny room which opens to one side, at first glance cosy enough for a meal by the fire, was the scene of one of the most famous murders in Scottish history…

On the evening of 9th March 1566, David Rizzio, a talented musician from Savoy, was sitting with the Queen and one or two of her ladies in this little supper room. Rizzio’s star was on the rise, and he was now so close to the Queen that he should have known he was heading for disaster. Mary had married her second husband, the vain and arrogant Lord Darnley, only the year before, but already she was regretting the decision; and there were rumours that the child she carried was Rizzio’s.

“There was then prevalent a report, that one John Damiot, a French priest, who was reputed a conjurer, told Rizzio once or twice, ‘That now he had feathered his nest, he should be gone, and withdraw himself from the envy of the nobles, who would overwise be too severe for him’; and that Rizzio answered, ‘The Scots were greater threateners than fighters’.” George Buchanan’s ‘History of Scotland’

If Rizzio had listened to this warning, he might have lived to pluck his lute another day. But Darnley was racked with jealousy, and that night something must have kindled his hatred to a flame. He and a handful of Protestant nobles swept upstairs to Mary’s chamber, overpowered her guardsmen, and stabbed Rizzio in her presence; the musician was then dragged, protesting and resisting, through the bedchamber and into the next room, where his murderers made sure he was dead. Mary was seven months pregnant at the time. When you think about it, it’s hardly surprising that James VI stuffed his garments with horsehair.

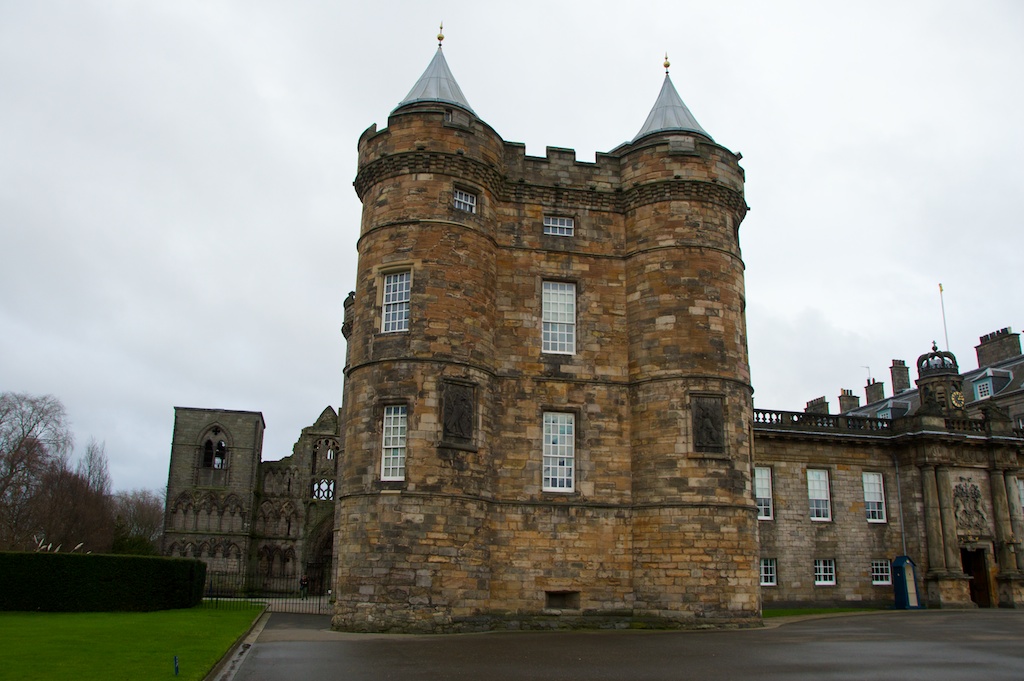

James V’s Tower. On the 2nd floor is the window of Mary’s bedchamber (2nd window up, between the turrets). To the left, in the turret itself, is the window of the supper room. You can see part of Holyrood Abbey in the background.

James V’s Tower. On the 2nd floor is the window of Mary’s bedchamber (2nd window up, between the turrets). To the left, in the turret itself, is the window of the supper room. You can see part of Holyrood Abbey in the background.

The sixteenth century historian George Buchanan wrote that Rizzio was first buried in haste outside the door of Holyrood Abbey; but he claims that Mary then gave orders for the body to be removed at night and placed in the tomb of James V, “which, being a most unaccountable action, gave occasion to evil reports.” Little more than a year later, Darnley himself was dead, in very suspicious circumstances, and Mary had a third husband in view: the Earl of Bothwell, whose involvement in Darnley’s demise has never been disproved.

I’m not entirely sure that I would like to be a tour guide stationed in either of these rooms, although the lady I spoke to seemed more than happy to be there. The antechamber with the infamous bloodstain now houses a collection of exquisite portraits and mementoes, many of them gathered by Queen Victoria and the 20th century Queen Mary. There’s a portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, apparently the only one painted during her lifetime: she is depicted ‘in white mourning’, after the death of her first husband, Francois II and her mother, Marie of Guise; I was quite shocked to see it, as there is no colour at all in her face. I’m guessing that this was deliberate, to enhance the effect – but how ironic that the paintings created after her death make her seem more alive.

The side of the James V Tower, showing the windows of Mary’s antechamber (centre, 3 rows up)

The side of the James V Tower, showing the windows of Mary’s antechamber (centre, 3 rows up)

Down some stairs, and you’re outside almost before you know it… to the fresh air blowing in from the Firth of Forth, low clouds scudding overhead, and a couple of gulls paddling happily for worms on the grass.

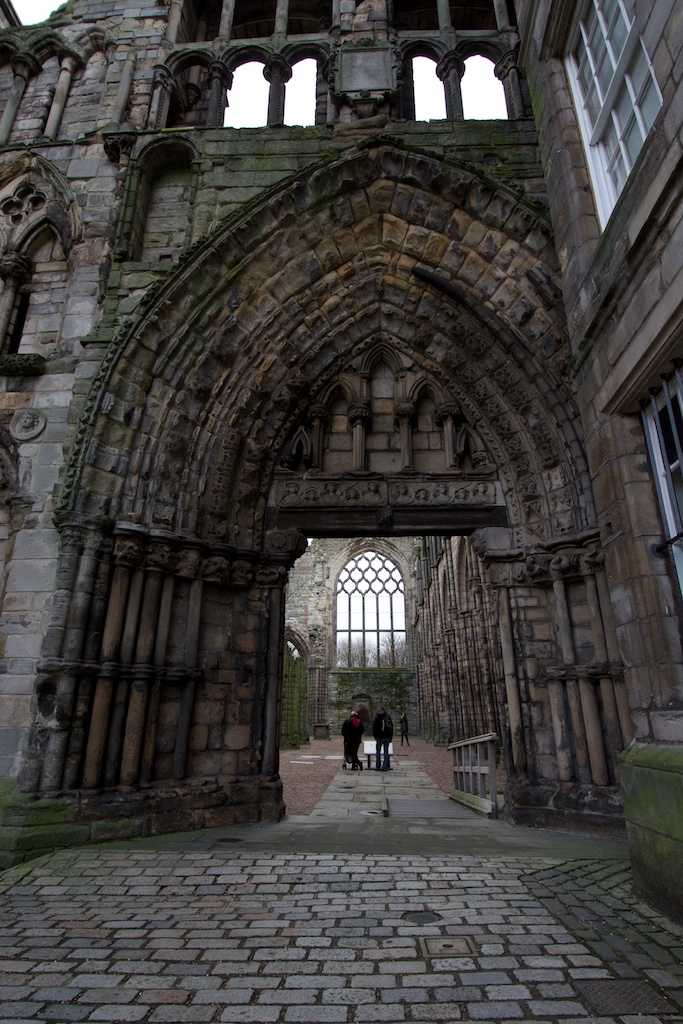

The evolution of the Palace

Not much survives of the original Palace which was the vision of James IV in the late 1400s. And it has to be remembered that Holyrood Abbey, which now lies in ruins and is easily outshone by its more glamorous neighbour, stood here for nearly 400 years before the earliest version of the Palace. Like Dunfermline, the Abbey had lodgings set aside for its royal patrons, and it was James IV who first thought about expanding them into a Palace. It is believed that the buildings were laid out around a quadrangle, with a tower (now gone) on the south side. James V had even bigger ideas, and in 1528 work began on a massive rectangular tower with turrets at each corner, which would contain the rooms of the reigning monarch.

Most of this was lost during the Civil War, when the Palace was occupied by Cromwell’s troops and then damaged by fire. Falkland Palace, which has similarities in its architecture, suffered the same fate. So it was down to Charles II, newly restored to the throne, to blow fresh life into the ashes. To do so, he commissioned the Scottish architect Sir William Bruce, who created a new Palace to a classical design which cleverly fused the old and the new. It was Bruce who added the turreted tower on the south-west corner, to match James V’s Tower; they look like a matched pair, but when you study them closely, you can tell that they are not: the biggest clue is the colour of the stonework. Meanwhile, to ensure that the interiors were jaw-droppingly opulent, a team of highly skilled craftsman was brought to Scotland by the Duke of Lauderdale.

Rows and columns: In the quadrangle, Charles II’s architect, Sir William Bruce, embellished each level of the facade with Ionic, Doric and Corinthian pillars in ascending order, from bottom to top.

Rows and columns: In the quadrangle, Charles II’s architect, Sir William Bruce, embellished each level of the facade with Ionic, Doric and Corinthian pillars in ascending order, from bottom to top.

Despite the triumphant arrival in 1745 of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the condition of the Palace gradually deteriorated in the 18th century; this didn’t deter early tourists, to whom the exploration of a romantic and dilapidated royal pile gave a delicious thrill of excitement. Queen Victoria saw its potential, and because she had already fallen in love with Scotland as a whole, she set about restoring Holyroodhouse as a royal residence once more.

Today, the Palace of Holyroodhouse is the official residence of the Queen in Scotland. Her Majesty stays here for a week during the summer, and it is used throughout the year by members of the royal family for official receptions and ceremonies.

At Holyrood, I found that some things which look old are comparatively new, while those that look recent are surprisingly old. The fountain in the forecourt (above), fashioned in the style of the much earlier version in Linlithgow Palace, dates from 1859.

At Holyrood, I found that some things which look old are comparatively new, while those that look recent are surprisingly old. The fountain in the forecourt (above), fashioned in the style of the much earlier version in Linlithgow Palace, dates from 1859.

Visiting Holyrood Palace

Holyrood Palace and Holyrood Abbey lie at the bottom end of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Full details of opening times and admission prices can be found on the official website. There’s a cafe in the courtyard – we had a nice lunch there – and the Queen’s Gallery hosts regular exhibitions of paintings.

Sources & quotes:

- The Palace of Holyroodhouse and official guidebook

- Historic Scotland

- ‘Holyrood, its Palace and its Abbey – an Historical Appreciation’ by William Moir Bruce (1914)

- ‘Black’s Economical Guide through Edinburgh‘ pub. A & C Black, 1843

Photos copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf

Further reading…

Further reading…

Check out my post on Holyrood Abbey, which is where the story began…

Or take a look at these features:

15 Comments

Susan Abernethy

Visiting Holyroodhouse Palace on my tour was one of the highlights. It’s so atmospheric. The royal bedroom is so small! When Rizzio was murdered it must have been terrifying with all those men in such a confined space. Looking forward to your story of the Abbey Jo. Those ruins are so beautiful.

Jo Woolf

I know, Susan, I remember reading your report! It made me wonder why on earth I hadn’t been there myself. But it more than lived up to my hopes! And Rizzio – yes, how awful it must have been. It’s too horrible to imagine. Looking forward to posting about the Abbey soon! 🙂

Pat

I find it hard to believe that horse hair could stop a knife blade. But looking at those pantaloons, maybe. 🙂 Great article and photos, Jo, thanks.

Jo Woolf

I know, Pat, it made me wonder, too, but then I remembered how hard the horsehair bed was at Drumlanrig, and if James’ pantaloons were as stiff as that I think you could have driven a truck over them without any real injury. Glad you enjoyed it, thank you! 🙂

mysearchformagic

Thanks for another great post. I visited the Palace last time I was up in Scotland, and really enjoyed it. I love the portraits of the mythical Kings of Scotland (who all look exactly the same!).

Jo Woolf

It was a pleasure, and thank you for your comment! 🙂 Yes, I did notice that about the portraits! They were quite entertaining, I thought!

blosslyn

One to go on the list, really interesting, I love anything about Mary Queen of Scots. I took some photos today of what is left of Fotheringhay Castle, where she was beheaded, only the motte is left now, but still very interesting. Yes lovely post 🙂

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Lynne – yes, something to remember when you’re in Edinburgh. You would love it. I’ve read about Fotheringhay, but never visited – would love to do so.

Fife Photos and Art

Great photos Jo, and a fascinating history of the place! 🙂

And I love the Sir Walter Scott tale about the blood stain!!! 🙂 🙂

Jo Woolf

Haha, thanks Andy! I loved that story too. I would love it to be true! Loved Holyrood but it gave me a strange feeling in places!

Fife Photos and Art

It sounds like perhaps you were picking up on some sort of spiritual/psychic activity – that’s not really my sort of thing, but my wife is very much into all that stuff, it sounds like she would love it at Holyrood! 🙂

Jo Woolf

Not sure, Andy, but there is definitely an atmosphere there. You would both love Holyrood, I think!

Fife Photos and Art

It certainly looks like a fascinating place to visit, if your description is anything to go by Jo! 🙂

bdean50

Wonderful descriptions. Almost as good as being there (and yes, someday I WILL make my pilgrimage)! Thank you!

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much! You are most welcome, and I really hope you come and see Holyrood for yourself! I’m sure you’d love Edinburgh very much.