A walk to Rí Cruin Cairn

It doesn’t seem like six weeks ago that we walked down the grassy lane to Rí Cruin, the most southerly chambered cairn in Kilmartin Glen’s remarkable ‘linear cemetery’. The roadside verges were high with the last wild flowers of summer, and the Kilmartin Burn was gushing after recent rain. We walked past the standing stones of Nether Largie, and turned the corner to walk along the road that runs along the bottom of the field. After a couple of hundred yards, one of Kilmartin’s blue-and-white signposts pointed the way, over a stone stile, to Rí Cruin Cairn.

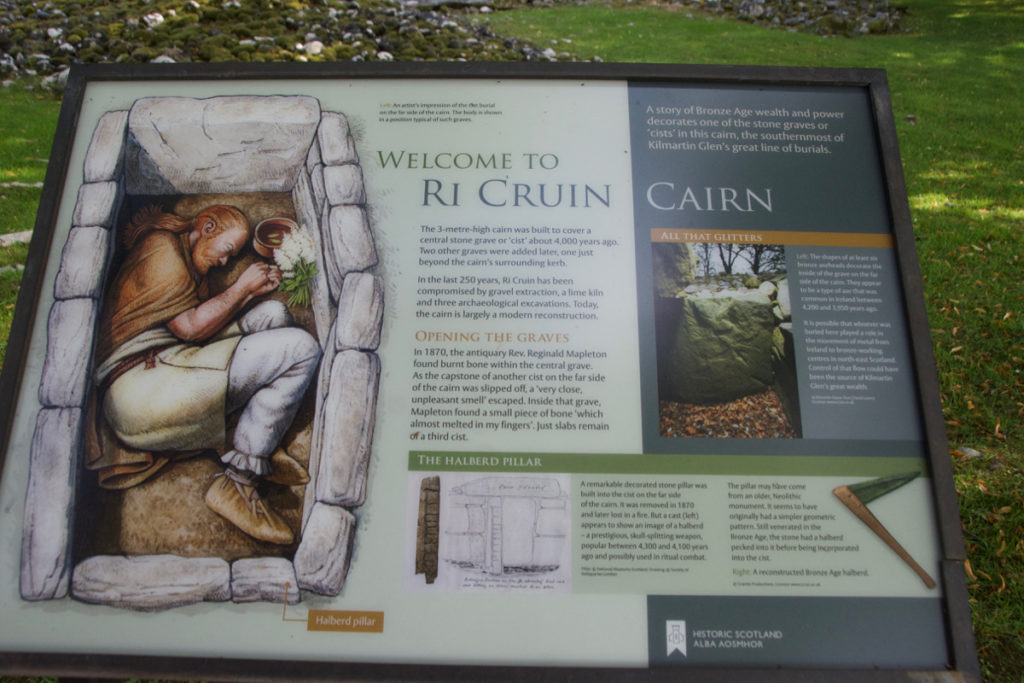

There’s a tradition that Rí Cruin is the last resting place of a king. The cairn covered a central grave or cist, and originally the heaped stones rose to a height of nearly ten feet, which would have been an impressive sight. It has been dated to the Bronze Age, between 2200 BC and 1950 BC. Sometime after the main burial, two more cists were added, nearer to the edge of the cairn.

There’s a tradition that Rí Cruin is the last resting place of a king. The cairn covered a central grave or cist, and originally the heaped stones rose to a height of nearly ten feet, which would have been an impressive sight. It has been dated to the Bronze Age, between 2200 BC and 1950 BC. Sometime after the main burial, two more cists were added, nearer to the edge of the cairn.

What we know about Rí Cruin hangs to a certain extent on the findings of an early archaeologist. In 1870 the Reverend Reginald J Mapleton, Dean of Argyll, conducted some excavations and was quite excited about what he found. He discovered three cists in a gravel bank; one of these had been partially destroyed in the comparatively recent construction of a lime kiln, and all that remained were two side slabs and an end slab.

The second cist, which lay about 21 feet to the north of the first, Mapleton described as being “beautifully formed… in fact, more artistically made than any I have seen before.” This was constructed of four slabs, grooved so that they fitted together at each corner, and a fifth had been laid on the floor; on this slab he found burnt bone, but no other remains or artefacts. He suspected that, since the cist had been “peeped into” and the cover dislodged, any grave goods might already have been removed.

The second cist, which lay about 21 feet to the north of the first, Mapleton described as being “beautifully formed… in fact, more artistically made than any I have seen before.” This was constructed of four slabs, grooved so that they fitted together at each corner, and a fifth had been laid on the floor; on this slab he found burnt bone, but no other remains or artefacts. He suspected that, since the cist had been “peeped into” and the cover dislodged, any grave goods might already have been removed.

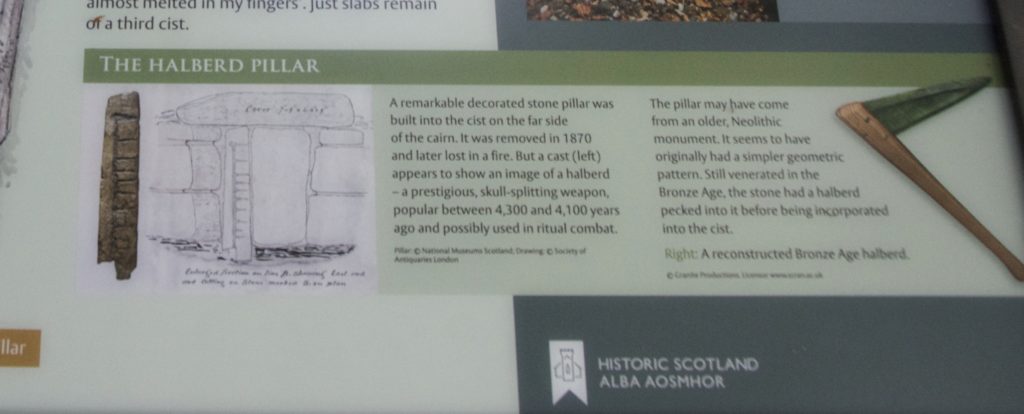

On the southern side of the mound was a third cist, of similar slab construction, which Mapleton believed had once occupied the centre of the cairn. This one grabbed his attention. On removing the cover, he immediately noticed what he describes as a small standing stone which formed part of one end of the chamber. This was about three feet in length and engraved with sculptures that gave him “the impression of their being large Ogham letters.” At the other end, a stone was carved with curious shapes which reminded him of bronze axe-heads, and the one next to it was pitted with small hollows “as large as a fourpenny piece.”

The southern cist (above and below)

The interior of the southern cist (above) showing the axe-head carvings. According to Historic Environment Scotland, they “appear to be of a type… that was common in Ireland between 4,200 and 3,950 years ago.”

While the axe-engraved stone is still in place and can be examined, the long stone with the curious Ogham-style carving was removed and later lost in a fire (although a cast had been taken). Today, the carvings on the stone pillar are interpreted as depicting a halberd – a simple but formidable weapon used in combat. Historians speculate that it may have come from an older monument of the Neolithic period, possibly because it was still venerated thousands of years later. On the information notice at the site there is a drawing of the lost engraved stone and an illustration of a halberd.

Mapleton remembered that, when the third cist was first opened, the clay inside was seen to be very dark, and the men helping him “complained of a very close unpleasant smell.” The floor was roughly paved with stone; it was empty except for “one minute portion of what I believe to be bone, not larger than a pea… which almost melted in my fingers.” Since the cist measured six feet in length internally, Mapleton considered that the body placed inside would have been extended, rather than placed in a sitting posture.

Mapleton remembered that, when the third cist was first opened, the clay inside was seen to be very dark, and the men helping him “complained of a very close unpleasant smell.” The floor was roughly paved with stone; it was empty except for “one minute portion of what I believe to be bone, not larger than a pea… which almost melted in my fingers.” Since the cist measured six feet in length internally, Mapleton considered that the body placed inside would have been extended, rather than placed in a sitting posture.

Apparently, similar axe-head style carvings have been found close by, in Nether Largie North and Mid cairns. Beyond Kilmartin, Historic Environment Scotland says that “the nearest known monument bearing Bronze Age representations of axes is Stonehenge in Wiltshire.” There must have been some real significance behind these, perhaps a depiction of wealth or status. It has been suggested that Kilmartin may have lain on an important route that saw valuable metal brought from Ireland to bronze-working sites in north-east Scotland.

Subsequent excavations at Rí Cruin were undertaken by J H Craw in 1929 and V Gordon Childe in 1936. While the cairn has been disturbed and robbed of stone over the centuries, it’s still curious to see the remaining mound of water-rolled stones, almost like a heap of cobbles, which sets you wondering why they were chosen by the cairn’s builders.

I was interested to see that the illustration on the board showed a bunch of meadowsweet among the offerings placed in the grave. When I wrote about meadowsweet a while ago, I discovered that traces of this pretty flower have been found in ancient burial sites in Perthshire and in Wales. In medieval times meadowsweet was used as a strewing herb, and the 16th century herbalist John Gerard favoured it because “…the smell thereof makes the heart merrie [and] delighteth the senses…”

I was interested to see that the illustration on the board showed a bunch of meadowsweet among the offerings placed in the grave. When I wrote about meadowsweet a while ago, I discovered that traces of this pretty flower have been found in ancient burial sites in Perthshire and in Wales. In medieval times meadowsweet was used as a strewing herb, and the 16th century herbalist John Gerard favoured it because “…the smell thereof makes the heart merrie [and] delighteth the senses…”

The tall trees that surround the cairn – mostly ash, beech, sycamore and lime – were swaying and whispering in the warm wind. There’s no knowing what the surroundings would have looked like 4,000 years ago, of course, but the atmosphere today is one of gentle seclusion. Surfaces are cushioned by plush green moss, and lichens flourish on bark and stone. The lovely old ‘ladder’ over a burn, which you must cross in order to enter the site, only enhances the fairytale effect. If there really was a king buried there, I’d like to think his spirit returns just as the moon is rising on a summer evening, and dances.

The four other cairns in Kilmartin’s linear cemetery include Nether Largie South, Mid and North, and Glebe Cairn. HES says: “This line of Early Bronze Age burial cairns, along the floor of Kilmartin Glen, was designed to be an imposing feature in a landscape that had already been marked as a significant place for ritual and funerary activity.”

Sources & more reading:

- Historic Environment Scotland

- ‘In the Footsteps of Kings’ by Sharon Webb, pub. Kilmartin Museum

- Canmore

- Undiscovered Scotland

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 11th April 1870: ‘Notice of Remarkable Cists in a Gravel Bank near Kilmartin…’ by the Rev R J Mapleton

Images © Jo Woolf

4 Comments

montucky

I very much enjoy your photos and your accounts of the history of your area. So far different from what little we have here.

Jo Woolf

I’m really glad you enjoy them – thank you! Likewise I enjoy seeing your magnificent mountain scenery through the seasons – it’s on such a magnificent scale.

Sandra

I’d like to think the same, Jo. Making that impressionistic, ethereal connection with such a place is as important as the tangible remains in my opinion

Jo Woolf

Well said, Sandra! There’s an unbroken human connection, after all. And I believe we can sense so much in the energy of these places.