Fincharn Castle on Loch Awe

There are several places that I’ve put off visiting until winter, when the trees aren’t in leaf and the views are more open. I hadn’t quite reckoned, however, on having near-continuous rain and wind from November until mid-January (only a slight exaggeration). But the other day there was a blissful lull in the weather so we ventured out to take a look at Fincharn Castle.

Dating from about 1240 AD, and now extremely ruinous, the castle sits on a small rocky promontory at the southern end of Loch Awe. You can’t easily see it from the road, but we had glimpses as we walked down through a hummocky field. At close range, with its shattered walls rearing up precariously from near-vertical rock faces, it looked quite imposing, and we also realised that it was going to be a scramble.

Originally this was a small, two-storey hall-house, rectangular in plan. It dates from around 1240 AD when some lands at Loch Awe were granted by King Alexander II to Gillascop MacGilchrist. The property subsequently passed to Master Ralph of Dundee and his descendants, John and Gilbert of Glassary; then to Ewen, brother of Gillascop MacGilchrist; and it eventually came into the possession of Alexander Scrymgeour, who was hereditary constable of Dundee and Robert the Bruce’s standard-bearer at the Battle of Bannockburn.

There is no immediate evidence about when or how it fell into ruin. However, according to a traditional story, a Scrymgeour laird, whose tenant was about to marry a beautiful local girl, decided to exercise his ancient right to share her bed first, so the bride’s family burned down Fincharn Castle in revenge. A slightly different version of the tale has the bridegroom himself setting fire to the castle on his wedding day and then forcing an oath from the laird at the point of his sword.

Grasping branches, we hauled ourselves up and stumbled into the interior. The floor is deep with the rubble of walls that have fallen inwards, but there’s still just enough of the structure left to give you a sense of its original dimensions.

Two windows facing north-east, one on the ground floor and one above, made me wonder who might have looked out of them, and what they were watching for. On the other side is a low lintelled recess, puzzling, and quite dry inside. I could see no signs of fireplaces: Canmore’s surveys suggest that there would have been a central hearth, with smoke escaping through a louvre in the timber roof. In the remains of the north-facing end wall, a big stone lintel juts out into thin air, perhaps having once supported a entrance.

In a cavity we found an old nest, perhaps a pied wagtail’s, lined with feathers and moss

In a cavity we found an old nest, perhaps a pied wagtail’s, lined with feathers and moss

We slithered down onto the shore at the south-west corner. Loch Awe was tranquil and reflective, rippling silently onto a beach of blackened pebbles. The promontory is girdled by ash trees which will screen the place effectively in summer; but on the walls themselves some stunted hawthorns have taken root. One of them, on the north-east side, made every attempt to deter us from getting in, while another sat atop the ruined wall like a vengeful crone. Strangely, the castle wasn’t forbidding at all: perhaps it was just the weather, but the whole place felt cocooned and peaceful.

Fincharn Castle takes its name from a mound about half a mile away, which was originally called Fiannacharn, meaning ‘the mound of the Fianna’. In Irish legend, which spread across the sea to Argyll, the Fianna were the fearless warriors of Fionn mac Cumhaill, whose hazel-wisdom gave him wonderful powers. I’ve come across echoes of Fionn and his followers in nearby places, such as the Tomb of the Giants by Loch Nell.

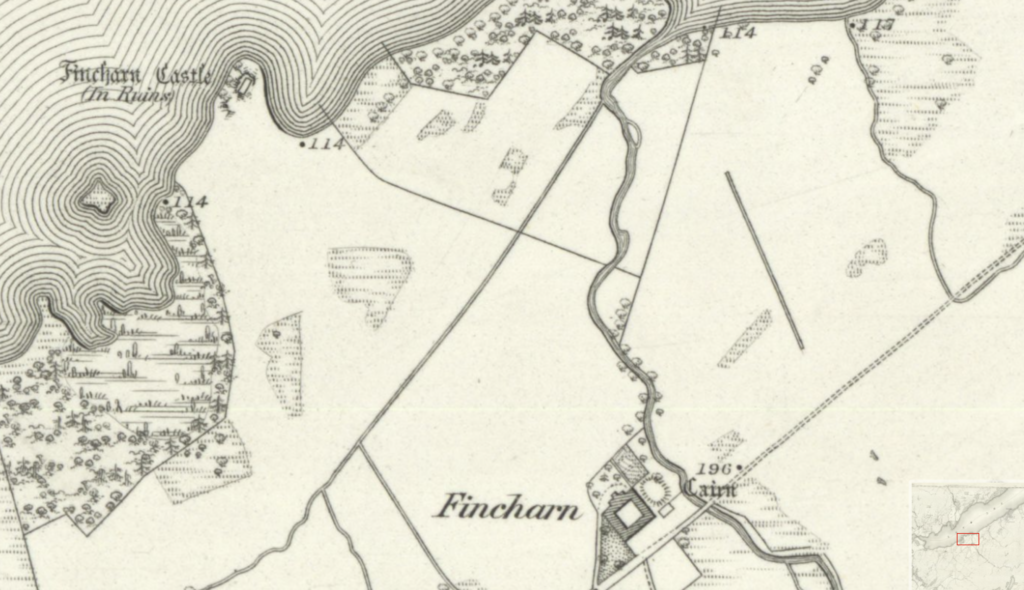

Located right next to a farmhouse, the mound of Fincharn is identified by Canmore as a cairn measuring just under 100 feet across. Although it has not been excavated, visiting surveyors identified a burial cist in the south-east; inserted into it on the west side is a large stone, under which, according to folklore, a horse was buried. It must have been a well-known site until fairly recent times, because an OS map from 1875 shows that the road – or track – along the side of Loch Awe once passed right by the mound, before skirting the chapel of Kilneuair.

1st edition 6″ OS map from 1875, showing Fincharn Castle top left and the road passing close to Fincharn farm and cairn. Map courtesy National Library of Scotland

A BIT ABOUT LOCH AWE

Towards the end of the last glacial period, about 10,000 years ago, a glacier lay in the valley which is now occupied by Loch Awe, and its meltwater rivers drained south through Kilmichael Glen, entering the sea at Crinan. But the gradual accumulation of debris at the south end of the loch eventually blocked the drainage route, and the water flowed instead through the Pass of Brander and into Loch Etive in the north. This is still the present route of the River Awe. Meanwhile, at the south end, little ‘kettle-hole’ lochans remain, formed by melting chunks of glacier ice.

An ancient story explains that Loch Awe was created by the Cailleach Bheur, the hag-goddess of winter and the bringer of autumn storms. She was said to be the guardian of a spring that bubbled up from the top of Ben Cruachan; to regulate the flow, she would place a stone slab over the source at sunset and remove it at dawn. One evening, she forgot and fell asleep; overnight, the water thundered down the mountainside, flooding the strath below and drowning the human inhabitants and their cattle before flowing out to the sea through the Pass of Brander.

Reference & reading:

- Mary MacGrigor, ‘Argyll: Land of Blood and Beauty‘ (2000)

- Canmore: Fincharn Castle

- Canmore: Fincharn mound

- Castle Finders

Images © Colin & Jo Woolf

12 Comments

Nicky

Wonderful, l love reading your blogs. The physical and the folktales are fabulous. Thank you

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Nicky! I know, I love the folk tales too!

Finola

In my next life I want to be called any one of the names in your third paragraph. Great day you had! I’m always struck, although of course it makes total sense, by the similarities with Irish myths and folklore.

Jo Woolf

Hahaha! 😀 That would be wonderful, although your name is beautiful anyway! I do love finding these traces of Irish myths. History revealing itself through stories – and I really want to go back and speak to the people who were here at that time!

davidoakesimages

Another good read…thank you. At least the weather was just a smidgen better than on your usual rambles 🙂

Jo Woolf

Thanks, David! Did you see, we even had a glimpse of blue sky? We were almost delirious! 😀

davidoakesimages

I did… I even looked twice to make sure ?

Jo Woolf

😀

Sue

Lovely little appreciation of Finchairn Castle. Approach with care from spring onwards, the birds nesting here are easily disturbed.

Jo Woolf

Thanks, Sue. Always important to remember, pretty much anywhere in nesting season – and if walking dogs, particularly along shorelines with ground-nesting birds.

Bob Hay

Good to see you back in the saddle Jo. Seems so long since your last article. I remember back in the 50’s when we did a lot of cycling and hosteling clambering over that hoary old ruin and wondering if it would collapse under us. Vey picturesque site. You’d want a metal detector on days out like that.

Jo Woolf

I’d like to have seen it in the 50s, Bob – sounds as if it was just as precarious. I don’t really know about a metal detector to be honest. I have often thought about it, and dreamed of unearthing a gold torc, but I still feel a bit ambivalent about digging around. However, ‘Detectorists’ is one of my all-time favourite TV series. I did say I was ambivalent! 😀