Orkney: the Brough of Birsay

In September, we spent a week in Orkney. It was our first visit, and it left us completely spellbound. Although I’m back now in the land of trees and soft rain, I’m finding it hard to forget Orkney’s cliffs and ferocious seas. If I was a Viking, I’d expect my longship to be carried on the kind of waves that break on Orkney’s shores, wild and terrifying, rather than the comparatively docile seas that wash the beaches of Craignish.

Where to start? The Brough of Birsay seems like an ideal place, largely because I love it. In the north-west ‘corner’ of the island of Mainland, a causeway is revealed twice every 24 hours at low tide. Leaving yourself enough time (ideally a couple of hours) to get back, you can climb down some steps onto the beach below and then walk across to a grassy island, topped by a lighthouse.

A few hundred yards to your right, which is pretty much due north, giant rolling waves, white-tipped and trailing plumes of spray, continue their regular pounding with a power that you can feel as well as see; to the south, where the sun is, the sea is like liquid metal, flanked by the dark cliffs of Marwick Head.

The natural platform on which the causeway is built is a mosaic of shattered rock ledges, still draining with the ebb tide. Rock pools are alive with hermit crabs, and little pockets of sand are sprinkled with limpets, periwinkles and brightly-coloured shards of sea urchin shells. If you’re lucky, you might also pick up a tiny cowrie.

A cowrie, lower left (above the orange scallop shell). Cowries are called ‘groatie buckies’ in the north of Scotland, and they’re said to bring good luck. The first part of the name (according to one source) derives from the place-name of John o’Groats, where the shells are quite commonly found, while the word ‘buckie’ comes from the Latin Buccinum, a genus of sea snails. Another account claims that ‘groatie’ refers to a groat, an old coin worth fourpence which was minted until about the mid-1800s.

The walkway is covered with seaweed, and you have to watch your step; it feels like a pilgrimage, and that’s really what it is. When you climb up from the shore to the island, with its wind-blown surface sloping gently up to a domed summit, you notice the remains of some stone buildings which include a church and a monastery. There’s a complicated history here, involving Pictish and Norse settlement, but what strikes you most is the atmosphere: calm, benevolent, free from the shackles of time.

It is has been suggested that Christian missionaries came here in the 5th century; in 1959, the archaeologist C A Ralegh Radford found evidence that a monastic settlement from this date lay beneath the surviving remnants of a later Norse church and monastery. But in the 7th and 8th centuries, before the Norseman arrived, Picts lived on the Brough of Birsay. Their most tangible relic is an impressive flat-sided stone, discovered in fragments in 1935, and carved with symbols that historians identify as an eagle, a mirror-case, a crescent and V-rod, and a Pictish beast. The significance of these symbols (although the eagle could be purely figurative) is obscure and still being debated.

The original Pictish stone is now in the National Museum of Scotland, and a replica stands in its place.

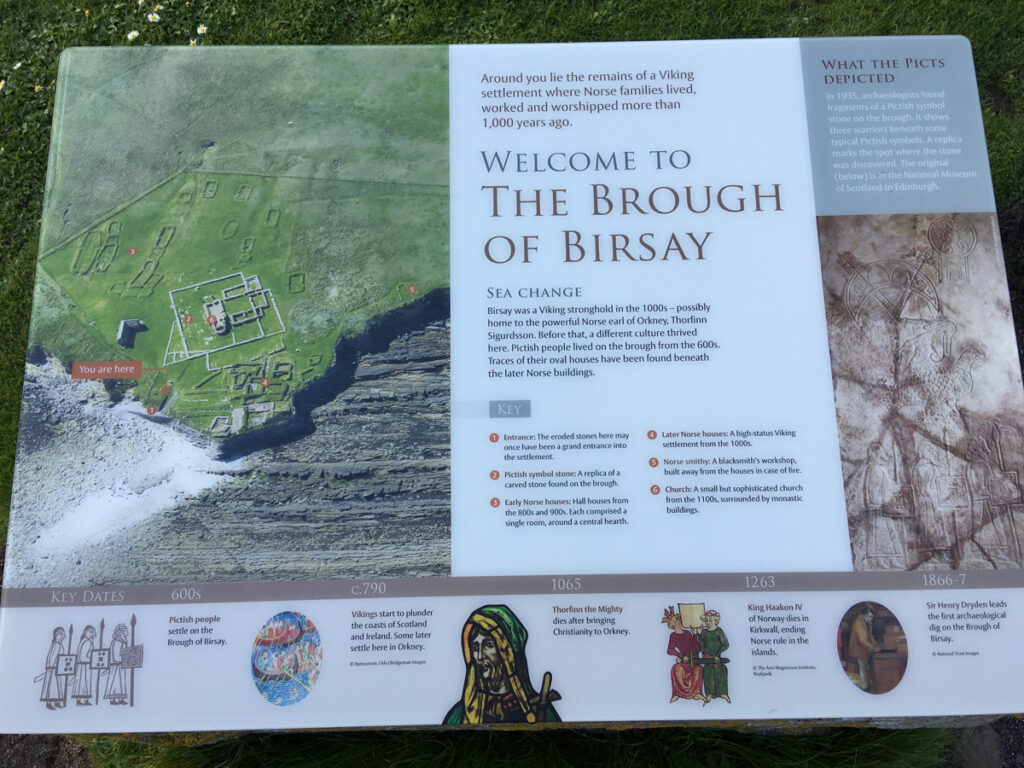

Information sign showing the layout of the site

A Pictish well, surprisingly small in diameter, has also been discovered, together with a number of objects including brooches, rings, dress pins and bone combs.

According to Historic Environment Scotland, the Brough of Birsay could have been a Pictish power centre; but in the early 9th century the Picts gave way to the Norse. This could have been a gradual process – some historians have argued for a fairly amicable mingling of cultures – or it could have been an abrupt and violent takeover. The same shift happened throughout Scotland, but nowhere did the enigmatic Picts leave behind any final message saying ‘this is what happened to us.’ (To be reasonable, if Viking raiders materialised silently out of the dead of night, no one would have had time to carve a report of their arrival into stone.)

Traces of Norse houses

Over the next 300 years, Norse settlers built houses and barns on the Brough of Birsay, and the remains of these can still be seen. The website of the Viking Ship Museum, Denmark, says: ‘On the east of the island, remains have been found of a very large hall-house with a sauna or bath-house attached. It has a central hearth, benches and evidence of a drain.’ It seems that the island, even then, had limited potential for grazing animals, so it has been speculated that inhabitants depended on supplies of food coming from the mainland. Iron-working was carried out, however, because a blacksmith’s workshop has been located, and the discovery of stone moulds suggests that precious metals were being cast.

Above and below: the remains of a church and monastery dating from the 12th century. The small Romanesque style church is described by Historic Environment Scotland as ‘one of the most sophisticated medieval ecclesiastical buildings to survive in the Northern Isles.’

Information sign illustrating the size and layout of the church and monastery

Looking back across the causeway. The island would once have been connected to mainland Orkney by dry land, but it isn’t known exactly when the link was severed by rising sea levels. What we might see as an inconvenience would once have been regarded as a distinct advantage, making the island easily defensible.

The words ‘brough’ and ‘birsay’ both come from the Old Norse ‘borg’ (‘fort’), but their meanings are slightly different. ‘Brough’ refers to the natural defences of the island. ‘Birsay’ (previously byrgisey) means an island accessible only by a narrow neck of land. (Historic Environment Scotland)

In the 11th century, either the island itself or a settlement just across the water on Mainland Orkney was the seat of power of Earl Thorfinn Sigurdsson, otherwise known as Thorfinn the Mighty. The Orkneyinga Saga, written around 1200, states that Thorfinn ‘had his permanent residence at Birsay, where he built and dedicated to Christ a fine minster, the seat of the first bishop of Orkney.’ It is not entirely clear whether this residence and minster were on the island of the Brough of Birsay, or on the mainland of Orkney, just across the water, where there is a settlement called Birsay.

Thorfinn’s mother (some sources name her as Olith) was a daughter of King Malcolm II of Scotland; she had married Sigurd Hlodvirsson, an Earl of Orkney. Thorfinn himself was described in the Orkneyinga Saga as being ‘the tallest and strongest of men, ugly, with black hair, sharp features, a big nose and a somewhat swarthy countenance. He was lucky in battle, skilled in the art of war and of dauntless courage.’ At the time of his death in 1065, the Saga claims that Thorfinn controlled Orkney, the Hebrides, nine Scottish earldoms and most of Ireland.

When Thorfinn’s grandson, Magnus Erlendson, was murdered by Haakon, his cousin and rival, on the island of Egilsay in 1116, his body is said to have been taken by ship for burial at Christ’s Kirk, the church that Thorfinn had founded. Magnus was declared a saint, and stories of miracles and visions experienced near his grave drew increasing numbers of pilgrims to Birsay.

Above and below: A small church occupies a site in the present-day village of Birsay, close to the causeway across to the island, where Thorfinn’s church is said to have been located. Originally called Christ’s Kirk, it is now dedicated to St Magnus.

In 1137, at the instigation of St Magnus’ nephew, Rognvald, work began on a magnificent cathedral in Kirkwall, with the purpose of creating a new shrine for St Magnus’ relics. (I’ll write more about this in a subsequent post.) Orkney stayed under the rule of Norway until 1472, when it was mortgaged in place of a dowry by Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, to James III of Scotland, who was marrying Christian’s daughter, Margaret.

I really didn’t want to leave the Brough of Birsay. I tell myself that it’s not so much a place as a feeling that you carry with you. From a human point of view, I’m pretty sure it’s a rough place to be when storms hurtle in from the Atlantic, and living there must have demanded extreme degrees of hardiness and resilience. But it’s that elemental power, that relentless crashing of sea against land, the yawning vastness of the sky, that completely invades your senses and holds you captive. I envied the flocks of golden plover and snipe wheeling in symmetry overhead, and the eiders, out at sea, floating nonchalantly over the crests of the swell.

Sources and reference:

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Canmore

- Orkneyjar

- Viking Museum, Roskilde, Denmark

- St Magnus Church at Birsay

The Brough of Birsay lies on the 58-mile St Magnus’ Way pilgrimage route across Mainland Orkney, from Egilsay to St Magnus’ Cathedral in Kirkwall.

Orkney is the birthplace of the Arctic explorer John Rae (1813-1893). On the RSGS’ blog, I’ve written about his early days in Stromness and employment by the Hudson’s Bay Company, and about his later life, surveying the coast of Canada for the Northwest Passage and traces of the lost Franklin expedition.

- John Rae: An Orkney Upbringing and the Call of the Sea

- John Rae: Scotland’s Forgotten Arctic Explorer

Images copyright Jo & Colin Woolf

19 Comments

Anne

A wonderful,evocative post, Thankyou.

Jo Woolf

That’s really kind, Anne, thank you!

Judy Lowstuter

Thank you for this great post. I’ve been to Brough of Birsay a few years ago and you take me back with your detail.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Judy! Glad you’ve visited, and have seen it for yourself.

davidoakesimages

A whole month on Orkney….WOW. I have only ever managed a few days at a time, both on Orkney and the Shetlands. Both magical places. Every visit, I say must go for longer…. even if the weather can be both wild and unpredictable, with 4 seasons in one day (no make that one hour !).

Jo Woolf

Hi David, it was only a week but it felt longer. We’d love to go back, if only to visit some of the islands. I love how the weather changed so rapidly – the rain soon blew over. Best wishes, Jo

Margaret Stewart

Birsay is my favourite place in Orkney. I’ve visited it for many years and miss it now I’m no longer able to make the journey. Thank you for sharing this post

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Margaret! I think Birsay is now my favourite place in Orkney too. I’m glad it took you back there in spirit!

Annette Marie Schmitz

How wonderful to live and visit places with so much history! We have a history here in the US, but it doesn’t come close to comparing with the timeline in the UK. I will never be able to afford to go to your beautiful country, so I greatly appreciate visiting these places vicariously through you!! Thank you!

Jo Woolf

You’re very welcome, Annette, and I’m so glad you enjoy seeing these places. Never say never, though – and if you get a chance, there’ll be a warm welcome in Scotland for you!

Karen Brooks

I imagined visiting Scotland long before I did through your stories . My sister and I were able to make the pilgrimage to Birsay in October 2021. I would go back in a heartbeat. Thanks for bringing back o fond memories.

Jo Woolf

That’s wonderful, Karen, and I’m glad to hear that you visited Birsay and loved it so much. It’s a very special place. I really want to go back!

Richard Miles

What a lovely piece of descriptive writing Jo.As you said,it’s often the feel of a place that leaves a lasting memory.I bet all those stone ruins could tell a tale or two.

Those Picts and Norse must have been tough to live in such a challenging environement.Would the climate have been any different then?The nearest to Orkney I have been is Wick where some of my Scottish relatives live.

Richard Miles

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Richard! I really don’t know if the climate would have been much different in Pictish or Viking times. There are some reports that it was warmer, but I’m not sure how reliable they are. We did briefly visit Wick on our way up, and Dunnet Head lighthouse which has amazing views out to Orkney. Really exciting to explore these places that we’d not seen before.

Bob Hay

Well Jo, brought up in school to look at the world through Mercator’s Projection makes it difficult to appreciate that these small islands were in centuries past, a hub of activity in Northern seas and pivotal in Scottish / Scandinavian history. I’m sure that there is a still a lot to be discovered there.

The great Orcadian Neolithic monuments were constructed almost a millennium before the sarsen stones of Stonehenge were erected. *

At one time it was believed that this flowering of culture was essentially peripheral and that its origins were to be found to the south on mainland Great Britain. However, recently discovered evidence shows that Orkney was the starting place for much of the megalithic culture, including styles of architecture and pottery, that developed much later in the southern British Isles.

* The recent discovery that the altar stone at Stonehenge was brought from many miles away (and Orkney was mentioned)makes you wonder if a deeply remembered spiritual power from these islands permeated down as far as Salisbury Plain.

Jo Woolf

All very intriguing, Bob. If the giants of ancient legend could be proved as real, it would solve one of the puzzles of transportation!

Bob Hay

I think the sea levels were lower then Jo and maybe not as rough up that way as today.

If it could be proved that the alter stone came from Cumbria and the almost impossible to believe, Orkney, then we are faced with a very big problem indeed as to how they got it there.

Might be simply a glacial erratic.

These are such stones I regret never visiting..

https://senchus.wordpress.com/2015/04/03/stones-of-the-britons/

Antony Duff

Thanks ever so much for bringing Orkney into the house. So interesting.

Jo Woolf

Glad that you enjoyed it! Much as I love Argyll, Orkney now has a special place in my heart.