Orkney: the Stones of Stenness

Moving on from the Ring of Brodgar in cool but clear autumn weather, we drove the short distance down the narrow isthmus towards the Stones of Stenness. What a magical place this is, half land, half water, the sun dazzling us with its reflections off the lochs on either side.

There’d been very few visitors at the Ring of Brodgar and although the Sunday morning was now well advanced I was expecting the Stones of Stenness to be reasonably quiet. How wrong I was. Passengers were disembarking by the score from a row of coaches that had pulled up, and the volume of people milling around the stones seemed bigger, in my mind, than the entire population of Orkney. The roads had been quiet – we’d barely met another car – so where on earth had they come from? (We discovered later that cruise ships often call at Kirkwall, some carrying up to a thousand passengers, and bus tours are laid on for them.)

On a weekday afternoon, things looked more promising. Stenness is an extraordinary place. Four megaliths, the tallest rising to over 19 feet (5.7 metres), stand in a grassy field. These are true behemoths, skyscrapers of the Neolithic world. Like most of the stones in the Ring of Brodgar, they are blunt-cut and flat-faced. Two of them are thick and hefty, shaped like the doorsteps of Valhalla, while a third seems impossibly slim for its towering height.

The curious chevron shape of the fourth stone, only waist-height to its siblings, put me in mind of a ‘sharp bend’ road sign. Were those reckless Neolithic drivers in danger of coming off the road?

The curious chevron shape of the fourth stone, only waist-height to its siblings, put me in mind of a ‘sharp bend’ road sign. Were those reckless Neolithic drivers in danger of coming off the road?

Despite the impressive size of the Stenness stones, I found the place hard to take in. For a start, no matter how you look at them, four stones don’t make a circle. There are big gaps in between them, and they’re arranged around some puzzling features in the centre. So what has happened here, and what was it like originally?

Firstly, it seems that the Stones of Stenness did once form a ring. Archaeologists have discovered traces of sockets, suggesting that the circle – which was in fact slightly elliptical – may have comprised 10 or 11 stones. The surviving stones came from multiple locations within Orkney, including Vestrafiold, which was also a source for the Ring of Brodgar. The site has been dated to between 3000 and 2900 BC.

Roughly in the centre of the circle, a two-metre-square hearth has been revealed. This was found to contain ash, burnt bone, charcoal and broken pottery. From these and other finds, it seems as if Stenness was the venue for some kind of feasting; it has even been suggested that a large Neolithic house once stood here. This is just one reason why Stenness is closely linked to a nearby site, called Barnhouse village.

Barnhouse village

In 1984, the remains of a Neolithic village were discovered, only a couple of hundred yards from the Stenness stones; the surviving structures are very close to the shore of the Loch of Harray, and it’s believed that more may have been lost to rising water levels.

Barnhouse is thought to have been in use from about 3115 BC until 2875 BC. This makes it roughly contemporary with Skara Brae, a Neolithic village on the west coast of Orkney, whose houses had similar architectural features.

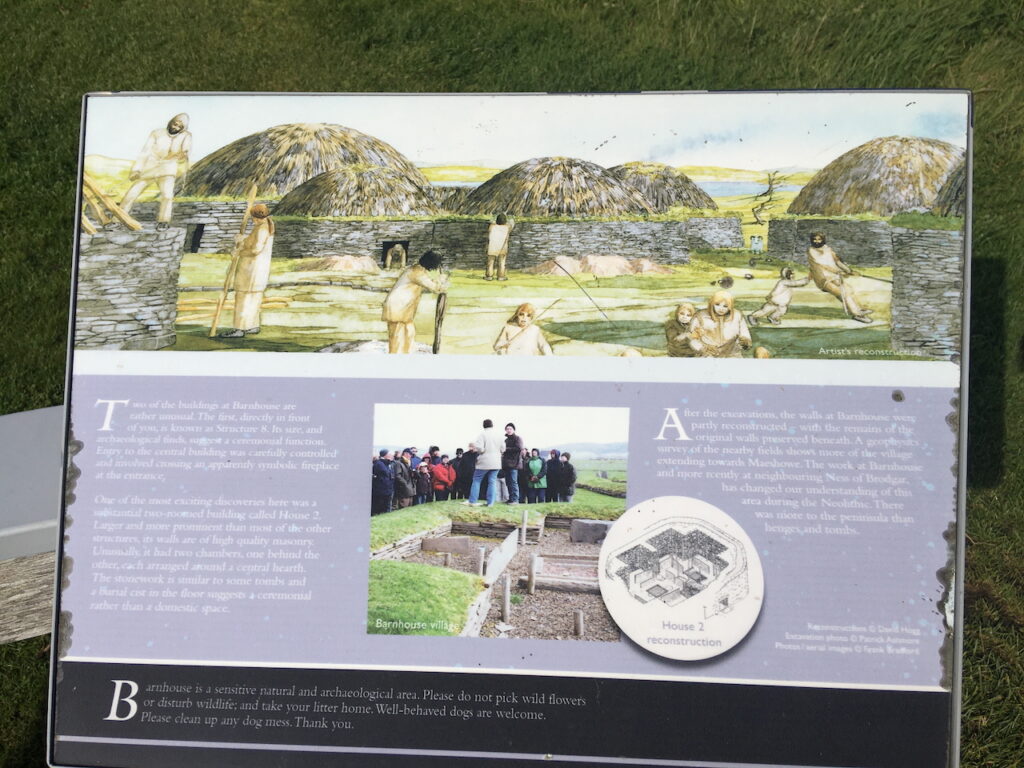

House 2 at Barnhouse. The information sign says: ‘One of the most exciting discoveries here was a substantial two-roomed building called House 2. Larger and more prominent than most of the other structures, its walls are of high quality masonry. Unusually, it had two chambers, one behind the other, each arranged around a central hearth. The stonework is similar to some tombs and a burial cist in the floor suggests a ceremonial rather than a domestic space.’

Archaeologists are still debating and interpreting the pattern of buildings at Barnhouse, and their puzzling chronology of demolition and reconstruction. Then there is the tangled question of how the inhabitants were connected with the Stones of Stenness, and how these two sites sit in the wider, complex landscape of the Ness of Brodgar. As with all these ancient places, there are still so many questions. A detailed description of Barnhouse and its buildings can be found on the Ness of Brodgar website.

Artist’s impression of Barnhouse village, on an information sign at the site

As far back as the late 1700s, the Stones of Stenness have been reported (or portrayed) as having only four megaliths still standing – less than half their original number. But even so, it seems that the survival of these stones is something of a miracle.

On 25th December, 1814, the historian Malcolm Laing was just sitting down to his Christmas dinner at his home in Kirkwall when he was interrupted by some very unwelcome news. A tenant who farmed the land around the Stones of Stenness had taken it upon himself to demolish the monument.

Laing was told that one megalith in the circle had been broken up by gunpowder, which was packed into holes drilled into the stone. Another lay on the ground with holes made ready for the explosive. An outlying stone, known as the Odin Stone, which stood to the north-west, had also been destroyed. Apparently, the farmer’s purpose was to obtain building material, and the fragments were being incorporated into some new cattle sheds.

Among Laing’s guests that Christmas Day was Orkney’s Sheriff Substitute – a judge in the local sheriff court – whose name was Alexander Peterkin. Immediately, Peterkin had a letter sent to the farmer, forbidding him from taking any more action. Such was the outrage among local residents that threats were made to the farmer’s person and his property, and legal proceedings were dropped when he promised to commit no further damage.

Just a few months previously, in the August of that year, the celebrated author Sir Walter Scott had visited Orkney, and had been shown around Stenness by a man called John Rae, a local landowner. (Rae held the position of factor for the Hudson’s Bay Company which was actively recruiting Orkney men, and hundreds of them crossed the Atlantic in search of adventure and lucrative work. Among them was Rae’s son, also called John, who became arguably the most skilled Arctic explorer of his age; I’ve written about him many times for RSGS).

Scott was very taken with Stenness, and he used it as the setting for a dramatic episode in his novel, The Pirate. In the story, two sisters, Brenda and Minna, take part in a clandestine meeting at ‘the Orcadian Stonehenge.’ Minna walks into the centre of the stone circle, where, according to Scott’s story, there was a flat stone resting on pillars in the form of an altar.

“Here,” she said, “in heathen times… our ancestors offered sacrifices to heathen deities…”

The trouble was that there were indeed some smaller stones inside the ‘circle’ of megaliths: two smallish slabs, one of which had fallen, and a much larger, flat stone, also lying on the ground. To the inexperienced visitor, especially one with 19th century notions of druids and human sacrifice, this little grouping could easily have suggested the existence of a pagan altar. Scott wasn’t responsible for sowing the seeds of that belief – it seems to have been current long before his visit – but it persisted well into the next century. When the monument was taken into state care in the early 1900s, a dolmen-style ‘table’ was actually created, using these three stones and an additional support. This structure stood until 1972, when its capstone was pulled off; it is once again lying on the ground.

The three stones that inspired the ‘dolmen’ idea

In the 1970s, an excavation of the site was conducted to try and determine its original appearance. The surrounding ditch – which, in early drawings, is closer to a semi-circle – yielded Neolithic pottery sherds and bones of cattle, sheep and dogs (or possibly wolves). In wet weather, the shallow trace of this ditch still pools with water, and it has been suggested that this was a deliberate feature of its design.

The Odin Stone

The destruction of the Odin Stone, which stood a short distance to the north-west of the circle, was particularly regretted because of the age-old stories associated with it. Odin, the Norse god, was known to possess powerful magic, and a large hole in the stone’s face was believed to have healing properties, especially when combined with water from the nearby well of Bigswell. Newborn babies were passed through the hole, and people would often put their heads or limbs through it, in hope of a cure for a wide range of ailments.

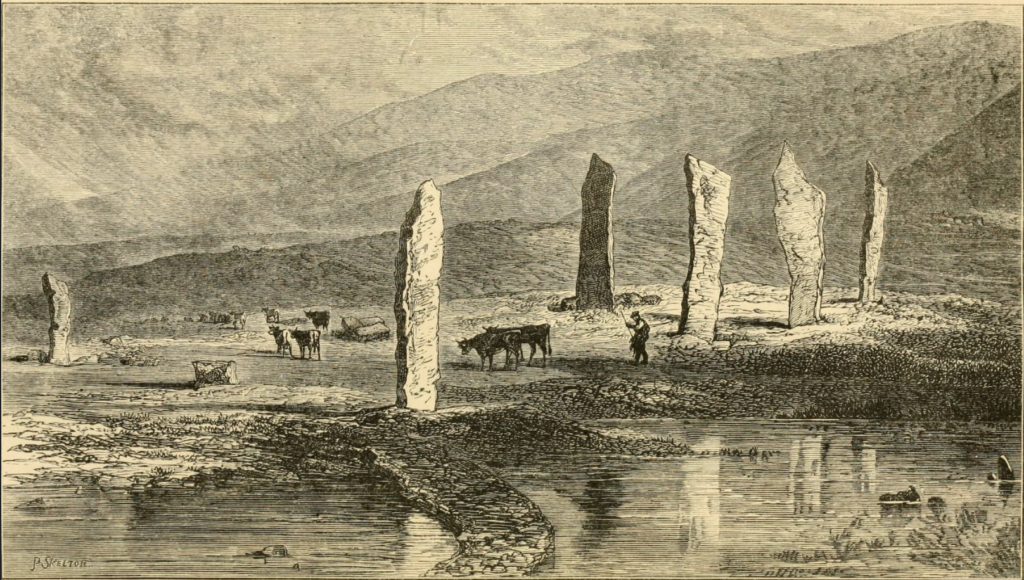

‘The Standing Stones of Stennis’, frontispiece to Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries by James Fergusson (1872). The Odin Stone is at far left, with the Watch Stone in the foreground. (The artist has been creative with relative distances.)

It’s interesting to note that, at least within the last few centuries (but not necessarily earlier), the Ring of Brodgar was known as the Temple of the Sun, and the Stones of Stenness were known as the Temple of the Moon. Writing in 1784, a local minister, the Reverend Robert Henry, described how lovers wishing to take an oath of fidelity would go first to the Temple of the Moon, where the woman prayed for the ability to fulfil the promise she was about to make, and then they went to the Temple of the Sun, where the man offered up a similar prayer; then they both visited the Odin Stone and linked hands through the hole, swearing to be faithful to each other. An oath made in this way was considered unbreakable, even after death; the only way to dissolve it was by both parties visiting the Stones of Stenness and for one to leave via the south entrance and the other to leave via the north.

The Reverend Henry also described how local people would gather at the Stones of Stenness (also known as the Kirk of Stainhouse) on the first day of every new year, bringing ample provisions with them, and they would hold a celebration of feasting and dancing that lasted for four or five days.

An old folk tale tells how a farmer from Evie used the Odin Stone’s magic to defeat the Finfolk, malevolent shape-shifting sea-dwellers who would snatch unsuspecting humans from the shore and bear them away to their watery stronghold. The farmer was known as the Guidman o’Thorodale, and he swore to take vengeance on the Finfolk after they captured his wife and took her off to the island of Eynhallow, which they had made invisible.

An old folk tale tells how a farmer from Evie used the Odin Stone’s magic to defeat the Finfolk, malevolent shape-shifting sea-dwellers who would snatch unsuspecting humans from the shore and bear them away to their watery stronghold. The farmer was known as the Guidman o’Thorodale, and he swore to take vengeance on the Finfolk after they captured his wife and took her off to the island of Eynhallow, which they had made invisible.

At first, o’Thorodale’s reaction was to leap into his own boat and row after them, but he found it was impossible because the Finfolk simply disappeared. Then one day, while he was still grieving, he was out fishing in calm water and heard his wife’s voice singing to him. She told him that he would never see her again, but that if he wanted vengeance on the Finfolk, he must consult the spae-wife (or seer) of Hoy. So the Guidman o’Thorodale took himself across to the island of Hoy, where the spae-wife assured him that he could avenge himself on the Finfolk by forcing them off their precious island of Eynhallow.

Just how he was going to find an invisible island was a secret that o’Thorodale took back home with him, thanks to the spae-wife of Hoy. For the next nine months, he obeyed her instructions: at midnight on every full moon, he crawled nine times on his bare knees around the Odin Stone, while wishing for the power of seeing Eynhallow.

On the ninth moon, that power was granted to him: the island appeared, and he made sure never to take his eyes off it. He summoned his three strong sons and together they rowed across, braving all kinds of perils that the Finfolk threw in their way: a giant whale that threatened to swallow the boat, two beautiful mermaids whose song almost lured them to their doom, and a fire-breathing monster with tusks as long as a man’s arm.

But the brave and resourceful Guidman o’Thorodale had brought with him a plentiful supply of salt, and he threw it in the faces of all these creatures, defeating each one in turn. Then, when he and his sons set foot on the island, they went around scattering more salt, so that the Finfolk – who could be heard but not seen – ran screaming into the sea, taking their bellowing cattle with them. O’Thorodale’s salt ran out just before he’d finished, which is why, so they say, Eynhallow is still a place of magic, where no iron stakes will remain in the ground after the sun has set, and no rats or mice can flourish.

Eynhallow seen from the East Mainland, just north of the Guidman o’Thorodale’s village of Evie

From early visitor accounts, it appears that the Odin Stone was about eight feet tall, and tapered towards its base. In the 1990s, an archaeological investigation located its precise position about 66 yards to the north-west of the Stenness circle, and it was revealed to have been one of a pair, with only 12 inches separating the two sockets. The second stone was removed in either the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age. A socket for a third stone was discovered about 23 feet away.

The Watch Stone

And finally to the Watch Stone, a magnificent 19-foot monolith which stands like a guardian by the roadside just north of the Stones of Stenness. Like the Odin Stone, the Watch Stone may have had a twin: in 1930, the stump of a second stone was found, some 40 feet away. The Ness of Brodgar website says:

‘These stone pairs have been likened to the door jambs of Late Neolithic structures and therefore may have represented symbolic doorways – perhaps marking, or controlling, movement through the landscape and the monuments.’

The Stones of Stenness left me overawed but also slightly baffled, as if there was something vital that I couldn’t grasp. Not so the Watch Stone, which just seems to draw you towards it.

According to legend, at midnight on every New Year’s Eve the Watch Stone treats itself to a celebratory dram: it will go down to the Loch of Stenness and dip its head into the water before returning quietly to its original position. But it was said that if you tried to witness this for yourself, something would always prevent you from getting there in time. (The distraction of the New Year festival in the Stones of Stenness might have had something to do with that!)

Reference and quotes

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Ness of Brodgar: The Stones of Stenness (part one)

- Ness of Brodgar: The Stones of Stenness (part two)

- Ness of Brodgar: The Barnhouse Settlement

- Ness of Brodgar: the Odin Stone

- Canmore: The Stones of Stenness

- Canmore: The Stone of Odin

- Orkneyology

- Rousay Remembered: How the Finfolk Lost Eynhallow

- The Orkneys in Early Celtic Times: Two Lectures by James M Macbeath (1892) via The Wellcome Collection

- James Fergusson, Rude Stone Monuments in All Countries; Their Age and Uses (1872)

- Sir Walter Scott, The Pirate (1822)

All photos copyright Colin and Jo Woolf

2 Comments

sallysmom

Oh my, what amazing stones.

Jo Woolf

I know, aren’t they incredible? As I said, so many unanswered questions!