The brochs of Glenelg

It’s quite a special day when you wake up to fresh snow on the mountains of Skye and a partially-eclipsed moon just setting in the morning twilight. The fact that the moon was, in fact, eclipsed, only dawned on me while I was half-asleep and staring at it shortly after 6 am, wondering why it didn’t look full, which I knew it should be, and why the illuminated part was pointing up into the sky when the sun wasn’t even risen. Sudden realisation sparked a scramble to locate cameras, whose batteries had chosen that moment to die, and point them at this spectacle in the last few seconds before it disappeared entirely from view.

We’ve just returned from a wonderful few days in Glenelg, a little village that looks north-west over the Sound of Sleat. The Isle of Skye and its mountains are just across the water. To the south are the wild peaks of Knoydart, to the north are the iconic summits of Wester Ross, and just to the south-west, rising out of a sea that seems to go on forever, are the islands of Eigg and Rum.

Apart from the Mam Ratagan Pass, notorious for its hairpin bends and dizzying views, the only roads out of Glenelg culminate in a dead end, either in the scattered coastal settlement of Arnisdale or in isolated hill farms to the east. Cattle or red deer might hold you up, or – as we found, to our delight – an otter, on its way back to the sea. If you happen to meet another car, there are passing places. You have to take your time. I don’t think you can live here and be in a hurry.

The Mam Ratagan Pass

Looking up the Sound of Sleat towards Kyle Rhea

The Road to Arnisdale

Looking across Loch Hourn towards Knoydart

Red deer stag

Arnisdale

In the summer months, a traditional turntable ferry – the last of its kind – operates across the narrow strait of Kyle Rhea. This photo was taken in 1993.

We last visited Glenelg when the girls were small. Back then, I wasn’t particularly fussed about historical sites, and when I glimpsed a dilapidated something from the car and saw a signpost ‘To the Glenelg Brochs’, I gave it no more than a passing thought. Last week, with early sun slanting down the long valley of Gleann Beag, I actually got out of the car and went to look. I was shocked, but I also had to laugh. If these places didn’t impress my younger self, then what would? Because they are absolutely amazing.

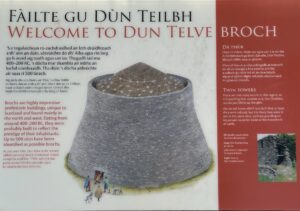

From the roadside, Dun Telve presents a curious ‘cooling-tower’ profile, which is what distinguishes the structure of brochs. Apart from Mousa Broch, which is on Shetland, I believe it is the best-preserved of its kind. It rises to over 30 feet (10 metres) high, and you can see that the stones used to build it have been carefully selected and dressed to a specific shape and size. Some are strikingly patterned, and some are just plain huge, but all have been placed by skilled human hands to form a perfectly tapering cylinder. It’s just incredible.

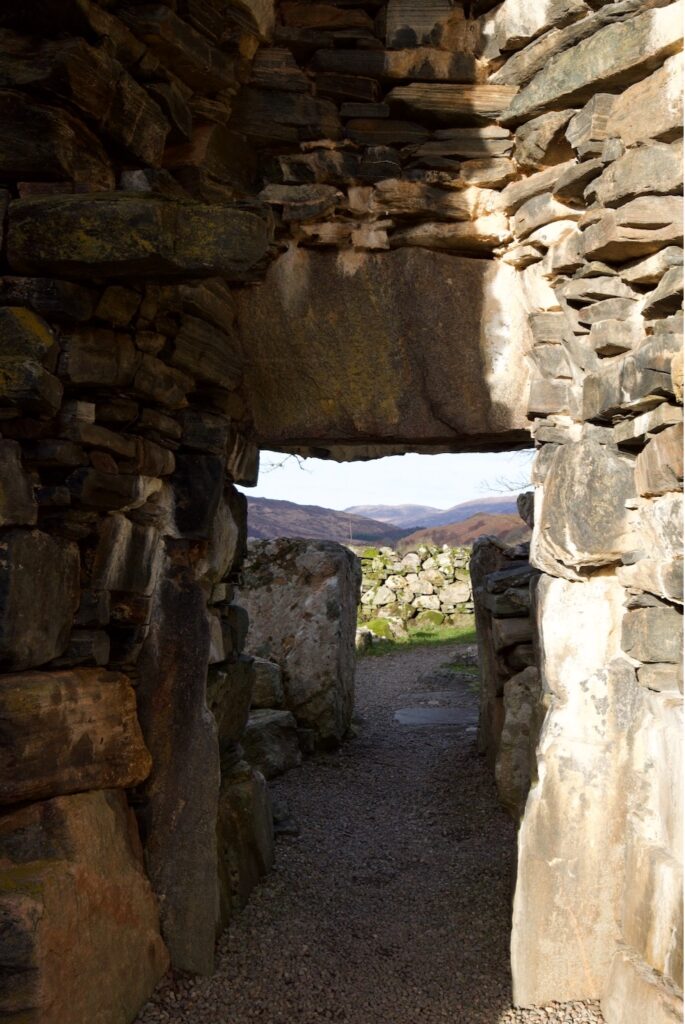

The low entrance is flanked by an arrangement of even larger boulders, of a size that wouldn’t look out of place in a stone circle or capping a chambered cairn. And then you duck under the massive lintel, suddenly aware of the weight of masonry above your head, and step inside.

Brochs are found throughout northern and western Scotland, with a few isolated examples in the Lowlands. They were built during the Iron Age – some sources offer dates of between 400 BC and 100 AD – and may have stood up to 16 metres (52 feet) in height. There is still debate about their purpose – whether they were built for defence, for prestige, or for domestic purposes, or a combination of all three.

Dun Telve still stands to a height of over 10 metres (32 feet).

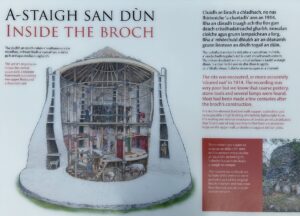

Their construction is quite extraordinary: two concentric drystone walls were tied together by horizontal slabs, the distance between them tapering gradually upwards from a width of about five metres (16 feet) at the base. This elegant design reduced the weight of the structure and allowed it to be self-supporting, while also providing great insulation. A Historic Environment Scotland sign explains that ‘some archaeologists believe that there must have been specialist broch-builders who moved from place to place.’

The slabs linking the inner and outer walls formed the floors of narrow galleries with an internal stairway between them, so that people could walk up and down between the two walls. Beside the entrance on the ground floor were small internal chambers described by archaeologists as ‘guard cells.’

Inside the broch, a large inner chamber may have contained one or even two floors above ground level, with the ground floor possibly used for housing livestock. One theory is that there would have been a conical thatched roof.

Apparently Dun Telve and its neighbour, Dun Troddan, were robbed of stone to build the nearby Bernera barracks, which housed Government troops after the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1715. At that time, Glenelg marked an important crossing-point between the mainland and Skye. Although they have been partly demolished, the damage does reveal the complexity of their inner stonework.

Information signs at Dun Telve, showing an artist’s impression of the original exterior and interior

As for the activities that went on in places like Dun Telve, we can only speculate. Illustrations on the information boards suggest the smoking of fish or meat above a central open fire. At Dun Telve, apparently, when the site was ‘cleared’ (probably of vegetation) in 1914, pieces of coarse pottery, stone tools and several lamps were found. Items unearthed at Dun Troddan include more stone tools and some glass beads.

While Colin prowled around the outside, taking some wide-angle photos and examining rocks for lichen, I took my flask inside Dun Telve and drank my coffee there while gazing up at those incredible walls. Although there was no wind, the air was cold and a light frost was thawing on the grass. A robin was singing from somewhere close by, and a pied wagtail was flitting about in the high stonework, possibly looking for somewhere to nest.

I knew there was another broch further up the glen – a rare occurrence, to find two so close together – and I wondered, why here? The woods flanking the river are rich in hazel, birch and willow, three extremely productive and versatile trees that would have been valued by early residents of the glen. The river’s flood plain might have been fertile, offering good grazing. There was a plentiful supply of fresh water, as well as fish and wildfowl, with deer on the hills. And with the proximity of the coast, travel by sea would have been easy. One thing that struck me was the siting of the broch on low-lying ground, rather than a hilltop or promontory. Did they have scouts posted up high? Or were they living in a time of peace?

One signboard suggested that the inhabitants of the brochs lived a fairly comfortable life: I’m not absolutely convinced about that, because they must have been as smoked as kippers, but they were probably warm and dry, if the theories are correct. And with such thick walls, they wouldn’t have heard much sound from the outside. This may explain the ‘guard cells’, which perhaps contained dogs (or a human watchman) to give early warning of danger.

Totally intrigued by Dun Telve, we wandered half a mile or so up the glen to take a look at Dun Troddan. This is in a similar ruinous state, but it is slightly more elevated than Dun Telve – at least, it sits higher than the present-day road. The structure is almost identical, although the interior struck me as being slightly smaller in diameter. An information sign revealed that a ring of post holes were identified during an excavation in 1920, suggesting the supports for a raised timber floor. Traces had also been found of a central hearth.

With no leaves yet on the trees, we noticed that you can actually see Dun Telve from here. But, as Historic Environment Scotland carefully points out, there is no evidence that both brochs were occupied at the same time.

As before, willow and hazel catkins were plentiful on the steep hillside. A thrush that had been investigating the stonework disappeared into the woods. Otherwise, nothing much was stirring, and we explored the place to our hearts’ content.

The fact that both Dun Telve and Dun Troddan contain the word ‘dun’ in their name but are, in fact, described as ‘brochs’ doesn’t do much to dispel my confusion about the difference between duns and brochs. As far as I can understand, duns were stone-built fortresses, dating from a similar era to brochs and often situated on good vantage points overlooking land and sea. There are duns throughout Argyll, and we’ve visited plenty of them. While I’ve seen duns that are irregular in shape, it seems that brochs are always circular in plan; however, there are ‘galleried duns’ which have double-thickness walls, and I’ve seen the word ‘semi-broch’, which may be the same thing. I think it’s a case of our understanding evolving over time. And that brings me to Glenelg’s ‘third broch’, which may be a dun…

On Canmore, the whole of Gleann Beag is sprinkled with promising little blue squares, and I’d noticed a place called Dun Grugaig at the head of the glen. This has been described variously as both a galleried dun and a semi-broch. On the ground, close to the last farm on the public road, it’s informally signposted as the ‘3rd broch’, and personally I preferred this description, only because I was amused by the extra finger vaguely pointing ‘Down There’, towards the river, but identifying nothing in particular.

It was a tramp of less than a mile to Dun Grugaig, on a farm track that led through a sheep field, over a ford (which you don’t see very often these days) and up a final incline towards a natural knoll. This promontory had a grove of birch trees to one side and a sudden drop down to the river in a deep ravine at its back.

Into this imposing outcrop of rock a fortress had been incorporated, so that it looked more like an outgrowth of the rock itself. Crumbling courses of stonework were mossed-over and vivid with all kinds of lichen. Looking at this decaying splendour, I can’t help wondering exactly how much ‘tidying up’ has happened in the past at Dun Telve and Dun Troddan.

A detailed report by the archaeologist Euan W Mackie is published on Canmore, in which he described Dun Grugaig as being D- or C-shaped rather than circular. He identified galleried walls and at least one entrance, and remarked that the way in which the walls had been laid on uneven, sloping ground was a testament to the knowledge and experience of its builders.

Mackie seems to have believed that this type of fortress preceded the ‘cooling-tower’ shaped brochs, because he concluded: ‘Dun Grugaig surely shows us that hollow-walled broch architecture had evolved to an extraordinary degree of sophistication before the round tower itself was developed. It is hard to think of any other reason why this building should have been put up on such difficult ground if the concept of a round tower suitable for flat land was already known.’

Mackie seems to have believed that this type of fortress preceded the ‘cooling-tower’ shaped brochs, because he concluded: ‘Dun Grugaig surely shows us that hollow-walled broch architecture had evolved to an extraordinary degree of sophistication before the round tower itself was developed. It is hard to think of any other reason why this building should have been put up on such difficult ground if the concept of a round tower suitable for flat land was already known.’

I can see his point. I don’t know if this theory is still current, that galleried duns such as Dun Grugaig were predecessors of brochs like Dun Telve and Dun Troddan. Maybe there was also a greater risk of attack when Dun Grugaig was built, making this location more attractive because it could be better defended. And then, as the inhabitants became more powerful or more secure, they moved down the glen into bigger and better accommodation. But it’s only an imaginary scenario.

I think perhaps it’s easier (and for me, it’s much more inviting) to embrace the traditional story, also mentioned by Canmore, that all these brochs were the towers of ‘Fingalian giants’ – the old name for the legendary hero Fionn MacCumhaill and his warriors, the Fianna. You can almost see them honing their fighting skills in the woods, armed only with hazel wands, or running across the hills with their hounds in reckless pursuit of ‘branchy deer’, or hefting those gigantic boulders around in tests of strength before repairing to their halls and feasting from cauldrons that fed thousands of men without ever becoming empty.

I think perhaps it’s easier (and for me, it’s much more inviting) to embrace the traditional story, also mentioned by Canmore, that all these brochs were the towers of ‘Fingalian giants’ – the old name for the legendary hero Fionn MacCumhaill and his warriors, the Fianna. You can almost see them honing their fighting skills in the woods, armed only with hazel wands, or running across the hills with their hounds in reckless pursuit of ‘branchy deer’, or hefting those gigantic boulders around in tests of strength before repairing to their halls and feasting from cauldrons that fed thousands of men without ever becoming empty.

Maybe they heard ring ouzels, like we did, singing unseen from a high perch overlooking a waterfall, and if the legends are anything to go by, they would certainly have had an eye on the cattle that were strolling at their muddy leisure across the track.

On our way back down the road towards the brochs, we stopped to investigate a chambered cairn in an adjacent field. This is Neolithic in origin, therefore likely to be at least 2,000 years older than the brochs. A huge capstone has partly collapsed over the internal chamber, and you could make out the faint trace of a roughly circular shape on the ground, which possibly represents the extent of a long-lost covering mound. Walking all round it, Colin noticed a strange stone at his feet, like a lump of rusting metal. Ironstone, he said, and took a photo.

We’d already seen seams of similar rock elsewhere on the peninsula, breaking up into sharp orange-red fragments on a footpath to the shore. A little piece which we brought home is strongly magnetic. Did the Iron Age broch builders know that it was abundant here? Has anyone found any evidence that they were using it? I don’t know the answers, but it’s a thought that interests me.

All photos copyright © Colin and Jo Woolf

Reference

Canmore:

Dun Telve

Dun Troddan

Dun Grugaig

Chambered cairn at Balvraid

Historic Environment Scotland: Glenelg brochs

Historic Environment Scotland: blog post by Kenneth McElroy on Building a Broch

Caithness broch project: What is a broch?

More posts about brochs on The Hazel Tree:

14 Comments

David Riggle

Thank you. Very interesting. More mystery…..

Jo Woolf

I’m glad you enjoyed it, David! Yes, there are lots of questions about these brochs and the people who lived in them.

Deb Vallance

When I read your descriptions and look at your pictures, I can truly imagine myself tramping along with you!

Your writing is wonderfully both lyrical and informative—thank you for sharing your adventures.

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Deb! I’m glad you enjoyed exploring the glen with us. I’m always a bit hesitant about going back to places we’ve visited so long ago, but in this case it was a magical experience.

Finola Finlay

Isn’t it funny that we still don’t know what brochs were all about? Spectacular post – really enjoyed it.

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Finola! Yes, it really is strange that we know so little about them. I’m in awe of the skill those builders had, though.

sallysmom

I was going to say that one of the photos was smashing but as I scrolled through them I have to say they all are. Just amazing!

Jo Woolf

Haha, thank you! It’s a stunning place, and we were absolutely blessed with wonderful weather.

Peter Berbee

Hi Jo,

I find these brochs fascinating. I wished I lived closer so I could visit, alas I\’m in Australia!

Thank you for your writing and blog.

Kind regards,

Peter

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Peter! Good to know you enjoyed it. I’m glad I finally got to look at these brochs properly because I’ve learned a lot about them myself.

Richard Miles

Absolutely fascinating Jo.I have seen one or two brocks in Argyll whilst visiting relatives,is it right that no mortar of any kind was used in their construction?

You were lucky to hear a ring ouzel this early .They used to be common here in Dartmoor,but they are very shy and put off by human activity,mainly increased tourism.

Great prose from you Jo and excellant photos from Colin.

Richard Miles

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Richard. Yes, they were of drystone construction, which makes them even more remarkable. We’re pretty sure it was a ring ouzel, its song was distinct from a thrush or a blackbird. We’ve already heard chiffchaffs here in Argyll (9th March), nearly 3 weeks earlier than the earliest we’ve heard them before.

Richard

Hi Jo,

Just to say that I haven’t heard a chiffchaff yet,it’s a bit strange as they usually arrive here in Dartmoor by now.I’m not sure about the migration routes the birds take,but from what I have read they usually return to their usual nesting areas along familiar routes.I write a nature notes column in the local parish magazine and last year we heard them on 11th March.I find bird migrations absolutely fascinating.

With kindest regards,

Richard Miles

Jo Woolf

That’s interesting, Richard. Since we heard that first one, we haven’t heard it again, but the weather turned suddenly colder afterwards with winds from the N and E. So really there’s no way of knowing if it (or they) are still here, or have moved on. I’ve kept a record of first birds since we moved here in 2018, and it now makes quite a good reference point for each spring. I also write down the date we last saw swallows, first heard deer roaring etc. Like you, I don’t know much detail about the routes taken by migrants – all I know is that the cuckoos that arrive here in Scotland take a different route from the cuckoos further south. With best wishes, Jo