The value of Stirling

The story of Stirling Castle is so inextricably linked to the fortunes of the Kings of Scotland – and England – that any feature about it is going to be a long one. So please make yourself a cup of tea!

‘HE WHO HOLDS STIRLING HOLDS SCOTLAND’

History seems to have conveniently forgotten who uttered this forceful statement, but its truth must have been ringing in the ears of Scottish monarchs and their adversaries over the course of many centuries, like a warning and a curse.

Stony-faced and defiant, Stirling Castle stands on a crag high above the city of Stirling. All around it is the flood plain of the River Forth, with wooded hills to the south and the distant summits of the Perthshire hills rising in the north-west.

The crag owes its appearance to glaciation, being a feature known as a ‘crag and tail‘. The ‘crag’ is a plug or outcrop of resistant rock – I would say that Stirling’s crag is volcanic basalt, although I’m no geologist. The ice sheet was forced to flow up and over it, creating a ‘tail‘ of land that escaped erosion, and this slopes gently away in the direction of the ice flow.

No one seems to know exactly when the first castle or fortress was built at Stirling. There has been speculation that the hill was fortified by the people of Manaw Gododdin in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, but there is no real evidence of occupation or activity until about 1107, when Alexander I of Scotland endowed a chapel in the castle. This implies that a castle was already in existence at this time, one that was sufficiently important to warrant the king’s attention.

No one seems to know exactly when the first castle or fortress was built at Stirling. There has been speculation that the hill was fortified by the people of Manaw Gododdin in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, but there is no real evidence of occupation or activity until about 1107, when Alexander I of Scotland endowed a chapel in the castle. This implies that a castle was already in existence at this time, one that was sufficiently important to warrant the king’s attention.

Alexander died here in 1124, and his successor, David I, made Stirling a royal burgh. William I, who was crowned in 1165 and became known as ‘the Lion’ because he sported a red lion rampant on his royal flag, created a deer park around the castle; but William was captured by English forces at Alnwick in 1174, during his bid to regain Northumbria for Scotland, and Stirling fell into English hands.

Fast forward a hundred or so years to 1297, and encamped on the plain below the castle were two opposing armies: one led by the Earl of Surrey, and the other, much smaller contingent by a rebellious Scottish landowner called William Wallace. We know how that one ended!

BATTERED BY CONFLICT

If you happened to be alive in Scotland around the dawn of the 14th century, you probably wouldn’t want to have been living in Stirling. There was really too much activity to expect a peaceful life. The Castle was a pawn in the ongoing power struggle between England and Scotland, changing hands several times; and then, in the summer of 1304, with the Castle bravely flying the Scots flag, Edward I of England appeared on the horizon, at the head of his formidable army.

Edward I was known as ‘the Hammer of the Scots’, and he was about to demonstrate why. Having laid siege to the castle for four months but to no avail, the English king lost patience. He drew up plans to construct a siege engine or trebuchet on a scale that would make the 30-strong garrison inside Stirling Castle stare in horror. He called this contraption the ‘Warwolf’.

The Warwolf took three months to build; based on the amount of timber that was used (30 wagons full), historians have calculated that it must have towered to a height of around 400 feet. As one of the first weapons of mass destruction, it was capable of slinging missiles weighing 300 pounds at the castle’s curtain wall.

Even before the Warwolf was complete, the garrison tried to surrender; but Edward wanted to see what his new toy could do, and he sent them all back inside so that he could try it out. He must have been overjoyed when his Warwolf laid waste to a large part of the castle’s curtain wall.

Stirling was now one of five Scottish castles held by the English; but that would all change in 1314, with England now under the weaker leadership of Edward II, and the Scots galvanised by the raw and ruthless ambition of Robert the Bruce. Just south of Stirling Castle lies the field of Bannockburn, scene of a triumph which is etched deep into Scotland’s history with blood and steel. Edward II was pursued to Dunbar, where he set sail back to English waters.

Nor did things quieten down in the ensuing centuries.

When James I was murdered in 1437, his wife, Queen Joan, fled to Stirling with their six-year-old son, who was now James II. And in 1452, the castle was the scene of a murder when James, aged 21, lost his temper and stabbed the Earl of Douglas, who had apparently been plotting against him.

THE RISE OF THE STEWARTS

Just 35 years later, the son of James III led a revolt against his father, and their two assembled forces clashed beneath the walls of Stirling Castle, on roughly the same fields as the Battle of Bannockburn. James III was killed, and his son stepped nimbly into his shoes as James IV.

The new king had obviously thought about his plans quite thoroughly, and he set in place a scheme of improvements and additions to the castle which would include the building of the Great Hall in 1504.

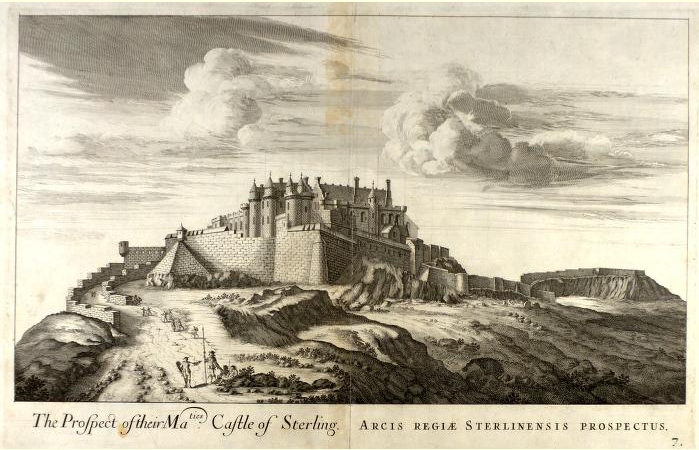

James IV was fascinated by the legendary tales of King Arthur, and the knights’ code of chivalry. His modifications to Stirling Castle included four entrance towers, tall and round, topped with conical turrets in the Camelot style. You can see them in this old engraving from 1693; the Great Hall is to their right.

Two of the towers still stand as part of the entrance gate, but they are less than half their original height. Nor would the walls have appeared dull and dirty, as they do today: they would have been washed with ‘king’s gold’, a glowing yellow limewash, and the effect would have been similar to the finish on the newly-restored Great Hall. Lowly visitors making their way up the hill must have been struck dumb with awe.

In 1507 a court physician called John Damian, who was also an aspiring alchemist, attempted to fly from the walls of the castle while wearing feathered ‘wings’. It is reported that he landed in a dung heap, and broke his leg. I am not sure how his career prospered after this incident.

Following the death of James IV on Flodden Field in 1513, his 17-month-old son, James V, was crowned in Stirling’s Chapel Royal. Obviously James was too young to rule, but the Scots weren’t struck with the idea of having his English mother, Margaret Tudor, as Regent, so they appointed James IV’s cousin, the Duke of Albany, in her place.

Margaret Tudor was the elder sister of Henry VIII of England, and her complicated personal life cast a shadow on her son’s childhood. In his youth he was kidnapped and held for two years as a virtual prisoner by his stepfather, the Earl of Angus, but he escaped in 1528 and from then onwards he managed to rule Scotland as a popular leader, often travelling in disguise so that he could mingle freely among his people. Intelligent but prone to alternating fits of severe depression and feverish energy, James V was described as ‘a good poor man’s king’.

James V lived to the age of 30, but he had an eventful life, fathering nine illegitimate children and marrying twice. In 1538 he married Madeleine of Valois, thereby renewing Scotland’s ‘Auld Alliance’ with France, but Madeleine died of tuberculosis just weeks after her arrival in Edinburgh.

A NEW PALACE FOR A NEW QUEEN

Two years later James married again, and he chose another French noblewoman: Mary of Guise. To impress her, he constructed the Castle’s magnificent royal lodgings, which are also known as the Palace. (So here we have an interesting take on the ‘castle versus palace’ conundrum: a palace within a castle!)

Arranged around a courtyard called the ‘Lion’s Den’, the Palace was decorated in the extravagant Renaissance style. There were separate bedchambers for the King and Queen, each with inner and outer antechambers in which privileged guests would wait for an audience. But James V may not even have seen his masterpiece finished, as he died in 1542, leaving his daughter, Mary, as Queen of Scots. Mary was just six days old. Nine months later, she was crowned in Stirling’s Chapel Royal.

In recent years, the walls and ceilings of the Palace have been the subject of an extensive restoration scheme funded by Historic Scotland and the Scottish government. Beautiful wall hangings have been commissioned to adorn the Queen’s Inner Hall, faithful replicas of the original Unicorn Tapestries which are held in a museum in New York. These tell the story of Christ, who is represented by a unicorn; the effect is quite magical.

On the top floor of the Castle is a display of the ‘Stirling Heads’, ornate circular carvings rescued from the ceiling of one of the royal apartments, each of which portrays a real or mythical character. These would have been brightly painted, and certainly very eye-catching. In fact, all of the decoration in the royal apartments has been painstakingly recreated to resemble as closely as possible the interiors of the time, and I was surprised to see the wealth of bold, rich colours and patterns. None of your barley whites or magnolias for the flamboyant Stewarts!

A DELIGHTFUL DISCOVERY…

The infant Mary, Queen of Scots grew up at Stirling Castle, before being sent to France at the age of five, to be safe from the menace of an increasingly hostile Henry VIII. When I was standing on the ramparts of Stirling Castle, a sudden thought came into my head – something I’d read in ‘A History of Scotland’ by Neil Oliver:

“The battlements are chest high, but at knee height there is a little spy-hole, maybe six inches across, cut through one grey block. It has been neatly and deliberately made… it is highly unlikely that you would ever imagine it was put there in the 1540s to let little Queen Mary – then just a toddler and being kept hidden from her great-uncle Henry VIII, lest he seize her as a bride for his baby son – look out over her realm.”

After just a few minutes of walking up and down the ramparts, I found this little hole. It is just as Neil Oliver describes, and a couple of steps have been created below it, to allow someone small to be seated while admiring the view. This simple feature struck me more directly than anything inside the castle – it was as if Mary was right there, not so much as a Queen but as a little girl, with boundless curiosity and energy. Other visitors were walking around me on the narrow ledge, and I had to stop myself telling them, “Look at this!”

PLEASURE AND PERSECUTION

If her father had had an eventful life, Mary’s was no less so. She married the 14-year-old Dauphin of France in 1558, but returned to Scotland after his death in 1560. It is said that she fell in love with her second husband, Lord Darnley, at Stirling, and their son, the future James VI, was baptised here at Christmas in 1566.

Royal baptisms these days tend to be low-key affairs, but the Stewarts weren’t having any of that nonsense. The entertainments lasted three days, ending with a banquet in the Great Hall. According to Stirling Castle’s website: “The guests sat at a round table, in imitation of King Arthur and his knights, and the food was brought in on a mobile stage drawn by satyrs and nymphs. A child dressed as an angel was lowered in a giant globe from the ceiling and gave a recitation. The banquet ended with a great fireworks display – the first ever witnessed in Scotland.”

The life expectancy of the royal Stewarts can’t have been great, but they certainly lived it to the full!

Having suffered the loss of her second husband – a mysterious murder in which she herself did not escape suspicion – Mary soon committed herself to her third, the unpopular Earl of Bothwell, who was rumoured to have plotted Darnley’s demise. In 1567 she visited Stirling Castle and saw her one-year-old son for the last time, before being forced to abdicate the throne and flee southwards across the border. In England, Mary hoped for the mercy of Elizabeth I; what she received was a cold welcome, 18 years of imprisonment, and a sad encounter with an axe.

MARY’S LEGACY

Back in Scotland, Mary’s son, James VI, survived the dubious care of several self-appointed Regents and grew up to marry the 14-year-old Anne of Denmark in 1589. Perhaps wishing to emulate the opulent style of his parents, James held a lavish banquet in the Great Hall to celebrate the baptism of his first-born son, Henry. According to reports, during the fish course a large model ship was brought into the hall, floating on an artificial sea and firing salvos from its 36 brass guns. (I’m assuming these were aimed towards the roof!)

The Great Hall, masterpiece of James IV: Built in 1504, and featuring a stunning hammerbeam roof (the current one is a 20th century replacement), Stirling’s Great Hall was the largest banqueting hall ever built in medieval Scotland. At the top end stood a dais or raised platform where the King and Queen sat on their thrones to dine and watch the entertainment. I would love to go back in time and see this spectacular space lit by a thousand candles, warmed by roaring log fires, noisy with the laughter of courtiers in rich garments and glittering jewels.

KING OF ENGLAND, SCOTLAND AND IRELAND

When Elizabeth I of England died in 1603 without naming an heir, James VI of Scotland was proclaimed the new King of England and Ireland mainly because of his family connection: remember that his great-grandmother had been Margaret Tudor, sister to Henry VIII. In one swift stroke of fate, James had achieved the prize that had been the curse and downfall of his mother. Elizabeth had always suspected Mary of plotting against her: how strange, then, that Mary’s son should sit on Elizabeth’s empty throne.

James, who was now James VI of Scotland and I of England, found his attention drawn towards London, and spent most of his time there. He wanted to call himself ‘King of Great Britain‘, although this was seen by both countries as an outrageous idea; and he penned a thesis on the Divine Right of Kings, explaining his belief that monarchs were higher mortal beings than other men. This attitude was going to cost his descendants dear.

Unfortunately for James VI, his first-born son, Henry, for whom all the elaborate pageantry had been arranged, died of typhoid at the age of 18. James’ second son, Charles, was now heir to the thrones of England and Scotland.

THE RAVAGES OF WAR

When his time came to rule, Charles was firmly based in London, but he visited Stirling Castle once, in 1633. Just 10 years later Charles’ kingdom was racked by Civil War, ignited by dissatisfaction in Parliament and fanned to a flame by an ambitious military leader known as Oliver Cromwell. Charles would no doubt have agreed with his father’s expressed opinion that “the highest bench is the sliddriest to sit upon.” Steadfastly refusing to accept the principles of a constitutional monarchy, he ended his life upon the scaffold in 1649.

For a few brief years, England was a republic; but in Scotland there were enough royalist sympathisers to offer shelter to Charles’ son, who, by rights, was Charles II. Charles stayed the night in Argyll’s Lodging, close to Stirling Castle, before being crowned King of Scots at Scone in 1651. With his supporters he moved south into England, but he suffered defeat at the Battle of Worcester and fled to Europe for his own safety. Later that year, Stirling Castle was besieged and overpowered by forces loyal to Cromwell. Charles had to kick his heels for another 10 years before the Restoration of the Monarchy allowed him to feel the crown of England on his head.

Over the next century, Stirling Castle witnessed three Jacobite uprisings, and withstood an attempted siege by Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1746. But its golden days were sadly waning: by the late 18th century the castle was being used as an army barracks, and in 1855 part of it was damaged by fire.

FALL… AND RISE

Queen Victoria, whose love of Scotland was all-encompassing, expressed her admiration of the castle during her visit to Stirling in 1849; but it was down to her son, Edward VII, to prevent it from falling into further decay by entrusting it to the government’s Office of Works. Even so, it wasn’t until 1964 that the Great Hall ceased to be a soldiers’ barracks, allowing a 35-year restoration project to begin.

Her Majesty The Queen officially re-opened the Great Hall in 1999, and in 2001 the restoration of the royal apartments was completed. Stirling Castle now glitters with the decadence of its grandest era, and actors dressed in period costume welcome visitors into the glorious rooms where James VI and V entertained their Queens, played with their children, laughed and argued with their court, hoped and dreamed, lived and died.

If you’re reading this…

Thank you for staying with me on what was a very long tour! I have loved researching and writing about Stirling Castle. Click on the image to read about Falkland Palace, another Stewart masterpiece!

Sources:

- Stirling Castle

- Historic Scotland

- The official website of the British Monarchy

- Royal Family History

- Undiscovered Scotland

- RCAHMS

- ‘A History of Scotland’ by Neil Oliver

Photos copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf