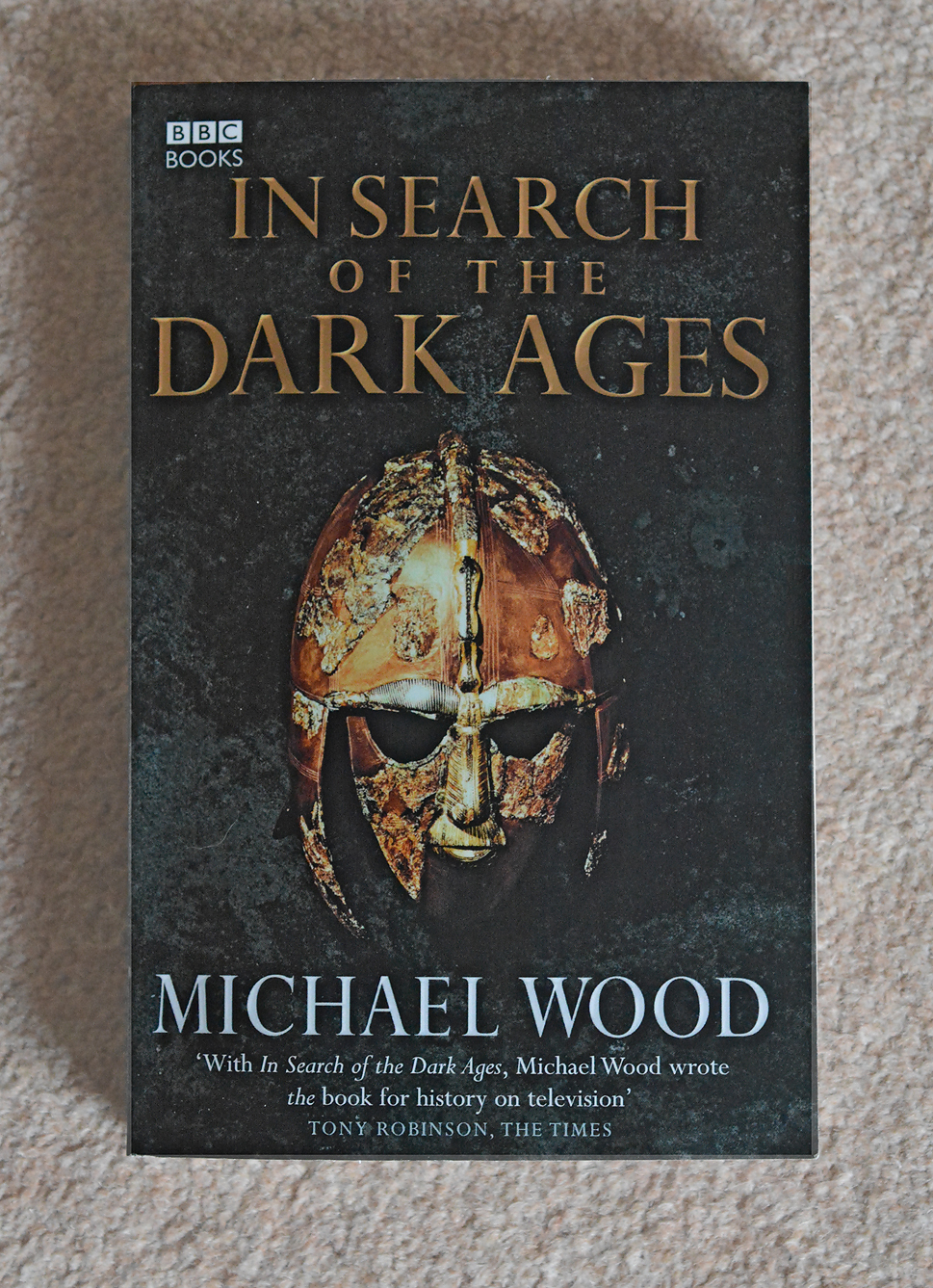

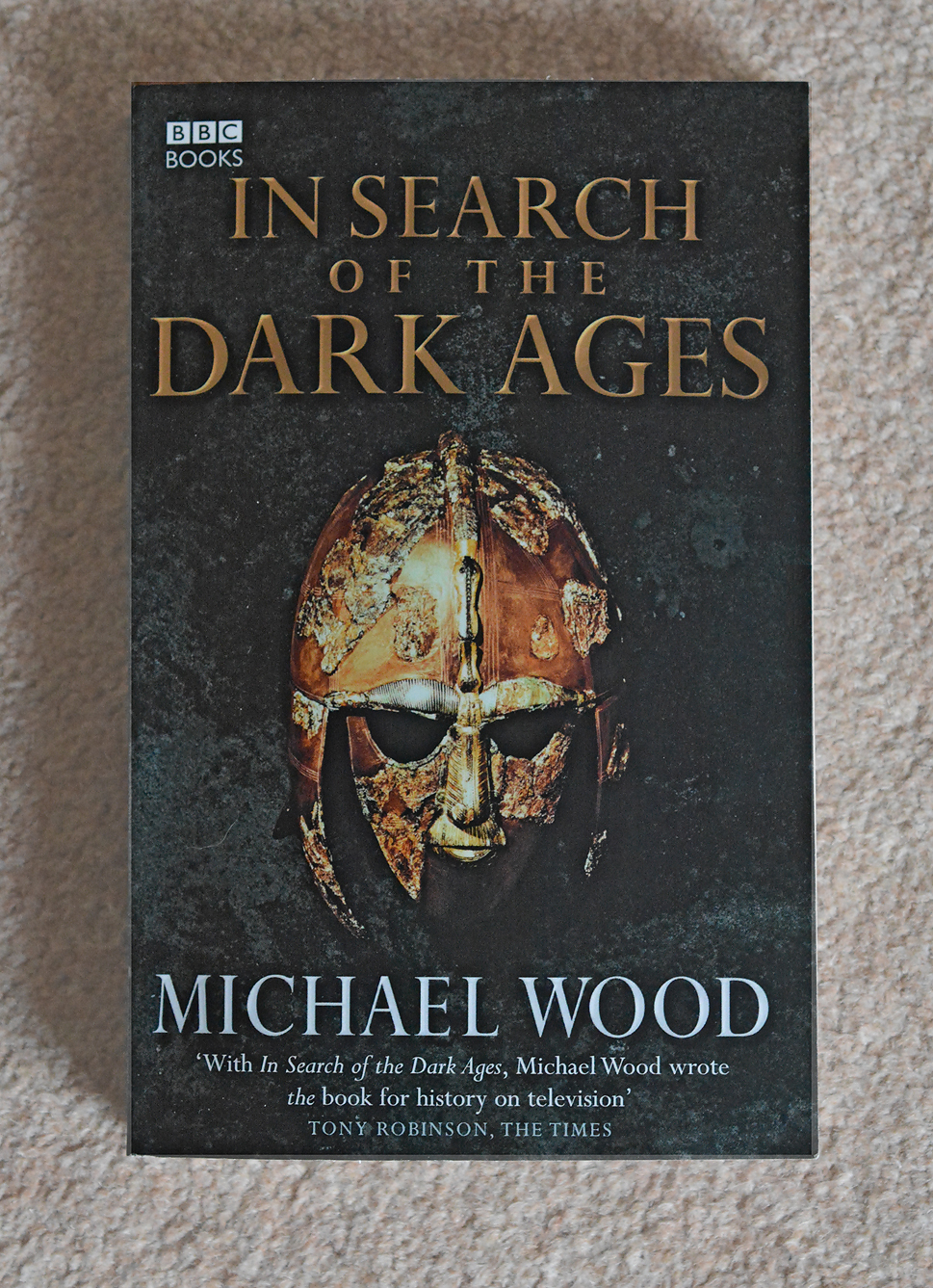

Book review: ‘In Search of the Dark Ages’ by Michael Wood

I f you’d been alive in England at any time between the first and tenth centuries AD, you would have had quite a few worries on your mind.

f you’d been alive in England at any time between the first and tenth centuries AD, you would have had quite a few worries on your mind.

It would have made no difference whether you were rich or poor, ruler or peasant. If you were a king, you’d never know which of your brothers, half-brothers or nephews was going to stab you in the night and claim your title; and as a humble farmer, if famine or plague didn’t get you, then warfare probably would.

The term ‘Dark Ages’ has always conjured in my mind a time of upheaval, invasion and barbarity; in AD 410, when the last of the Roman legions departed our shores to deal with troubles closer to home, it’s as if the last one to leave put all the lights out.

This was a time before England’s identity had taken root, when even the concept of English-ness was unknown and unrecognised by its inhabitants. The Celtic tribes, some of whom had assimilated the lifestyle of the Romans, found their wealth and security ebbing away; and on the next tide came a fresh wave of conflict, in the shape of the Anglo-Saxons.

Michael Wood is a well known historian and presenter whose knowledge always leaves me in awe. His journey through the Dark Ages begins with one of history’s most enigmatic characters.

Setting the scene in AD 60, just after the death of Prasutagus, King of the Iceni, he says:

“It is the story of the bitterest war ever fought in Britain; a desperate colonial war which saw the destruction of the largest Roman towns… the deaths of 70,000 colonists and untold numbers of Britons.

None of these things was new to the Roman conquerors; what made this war exceptional was that they had to fight for their lives against a woman.”

Enter Boadicea, flame-haired widow of Prasutagus, whose outrage at the treatment of her people knew no boundary and no fear. Riding at the head of her army, she blazed her way through the Romano-British settlements of Colchester, Chelmsford and St Albans; and before the legions could turn back from their engagements further north, she had razed the prosperous city of London to the ground.

Boadicea left a lasting mark. Wood says:

“Whenever you dig into the foundations of London you come across a red and black layer of burned ash and soot.”

From here, Wood leads us through the turbulent years of Anglo-Saxon invasion, briefly examining the evidence for the Arthurian legends and describing the possible circumstances behind the richly endowed ship burial at Sutton Hoo. With him, we visit the magnificent palace of ‘Good King Offa’ at Tamworth, and learn why the country was left so much stronger after the death of this ‘great warrior’; and we realise that, far from chiding Alfred for burning some cakes, we should, in fact, be honouring him for saving the last few acres of England from the bloodthirsty grasp of the Vikings.

Have you heard of the Battle of Edington? I confess that, up until now, I hadn’t. Wood doesn’t mince his words:

“If Alfred had given up and fled overseas… then not only England but the whole English-speaking world would not exist today.”

Woven into the thread of England’s fortunes are the kingdoms of Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Northumbria; of these, it seems that the kings of Northumbria were the thorniest and most enduring problem. Eric Bloodaxe, whose roots lay in Norway, presided over a Northumbrian population that was described was “treacherous, stubborn, violent and rebellious”, ready to throw in their lot with any leader who offered them independence from southern rule.

Offa, Alfred, Athelstan, Edgar… all great kings, brutal by modern standards but feared and honoured beyond the shores of England. Through their far-sighted wisdom, commitment and courage, the country and its people prospered.

Then we got Ethelred:

“The king, eager and admirably fitted for sleeping, put off such great matters (that is, opposing the Danes) and yawned, and if ever he recovered his senses enough to raise himself upon his elbow, he immediately relapsed into his wretchedness, either from the oppression of apathy or from the adverseness of fortune.”

William of Malmesbury, 12th Century chronicler

Wherever there is a temptation for wry comment or criticism, Wood steps nimbly around the pitfalls while still managing to maintain our interest. His passion for the characters, the places and the landscape never wavers; he sits just on the informal side of academic, his story-telling enthusiastic but unbiased, with a talent for painting scenes so vivid that I found myself reading them twice, just for pleasure.

The only aspect of his writing that I find disconcerting is an occasional tendency to flash forwards and then backwards in a character’s life or reign, especially if their death was a pivotal event; this, in a period of history that is rife with similar-sounding names like Aethelwulf, Aethelbald, Aethelberht and Athelstan (‘athel’, in Middle English, means ‘noble’), certainly stops your attention from drifting off.

Wood concludes his saga with the Norman Conquest, when William of Normandy brought the golden era of Anglo-Saxon kings to an abrupt and ruthless end. About the invasion, he says:

“No event has provoked more controversy. It has been viewed both as England’s most lamentable defeat, and as the foundation of her greatness.”

Surprising, shocking, moving, inspiring… ‘In Search of the Dark Ages’ is all of these. Wood transports you expertly from the tradesmen’s shops of Roman London to the marshes of Athelney, where Alfred made his heroic stand; and from Athelstan’s court at Dorchester to the prosperous Viking quarter of tenth-century York.

Educational and enjoyable… all history books should be like this!

‘In Search of the Dark Ages’ by Michael Wood is published by BBC Books