Book review: ‘The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland’ by Clifton Bain

You might remember that, back in the summer of last year, I wrote about the oak woods of Taynish in Knapdale. These are one of the last remnants of Britain’s temperate rainforests, having flourished in the mild, moisture-laden climate of the west coast for around 7,000 years. It’s an enchanting, invigorating place: in spring, as you walk in dappled shadow beneath the freshly-emerging canopy of leaves, you feel as if you’re breathing the same air as Argyll’s ancient ancestors.

You might remember that, back in the summer of last year, I wrote about the oak woods of Taynish in Knapdale. These are one of the last remnants of Britain’s temperate rainforests, having flourished in the mild, moisture-laden climate of the west coast for around 7,000 years. It’s an enchanting, invigorating place: in spring, as you walk in dappled shadow beneath the freshly-emerging canopy of leaves, you feel as if you’re breathing the same air as Argyll’s ancient ancestors.

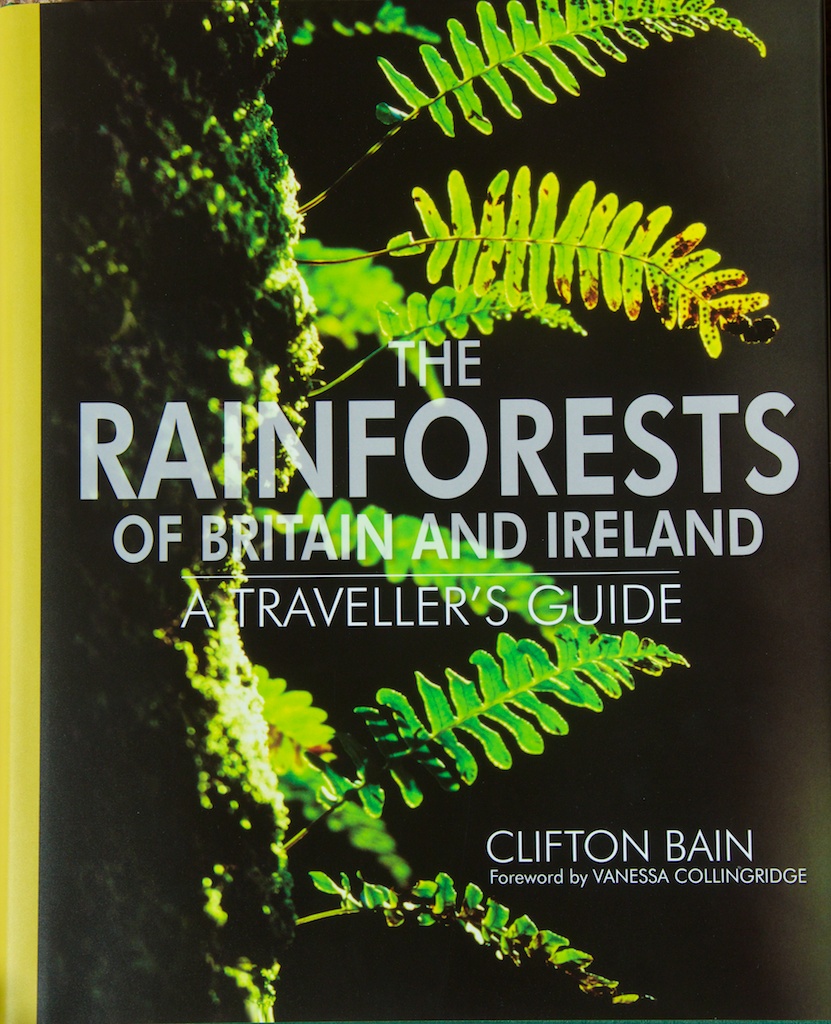

I was therefore delighted to come across a new book entitled ‘The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland – A Traveller’s Guide’. Written by Clifton Bain and published by Sandstone Press, it is a celebration of these age-old realms of leaves and lichen, describing their natural history, their evolution over time, their links with human activity, and the ways in which they are being managed and preserved for the future.

The book opens with an insight into the temperate rainforests of the world: these fall into eight regions, from Pacific north-west America to south-west Japan and New Zealand. I was interested to read that their defining features include an annual rainfall of over 1,500 mm (59 inches), with rainy days occurring on more than two-thirds of each year. Of these, Britain’s own rainforests enjoy one of the wettest climates, with an annual rainfall that can exceed 4,000 mm (that’s over 13 feet of rain!) This, with the addition of sea mists, makes an ideal environment for mosses, ferns and lichens to thrive.

“For thousands of years humans have interacted with these woods. In ancient times as people travelled mostly by boat, the eastern Atlantic was a major sea-going highway with communities settling all along the west coast of Britain and Ireland. Later, as agriculture developed, many woodlands were converted to grazing pasture and arable crops or managed as coppice, leaving the small remnants we see today in the least accessible places with poorer soils.”

Oak is the predominant tree species in many of our rainforests, but in the far north-west of Scotland it gives way to birch. The rapid expansion of oak woodlands since the last ice age is highlighted as a particularly intriguing phenomenon: as acorns tend to fall close to the parent tree, the author explains that it should have taken 100,000 years for oaks to reach Scotland from the Pyrenees – yet pollen studies prove that they got here within 3,000 years. How did this happen? The answer could lie with the jay, whose habit of burying acorns over a wide area may have helped to bring oaks to Britain before it was cut off from the rest of Europe by rising sea levels. What a lovely thought!

The impact of human presence since prehistoric times is described, with insights into how man learned how to manage the woods and the uses he found for the timber; around 6,000 years ago, Neolithic farmers were merely creating clearings in the forest in order to build dwellings and keep cattle, but from the Iron Age onwards the refinement of tools and the need to make way for agriculture sparked the first serious incursions into our ancient rainforests. Then, through medieval forestry practices and a neat explanation of coppicing and pollarding, we make our way to the 21st century and modern management policies which are influenced by the need for careful conservation alongside the provision of public information and access.

The impact of human presence since prehistoric times is described, with insights into how man learned how to manage the woods and the uses he found for the timber; around 6,000 years ago, Neolithic farmers were merely creating clearings in the forest in order to build dwellings and keep cattle, but from the Iron Age onwards the refinement of tools and the need to make way for agriculture sparked the first serious incursions into our ancient rainforests. Then, through medieval forestry practices and a neat explanation of coppicing and pollarding, we make our way to the 21st century and modern management policies which are influenced by the need for careful conservation alongside the provision of public information and access.

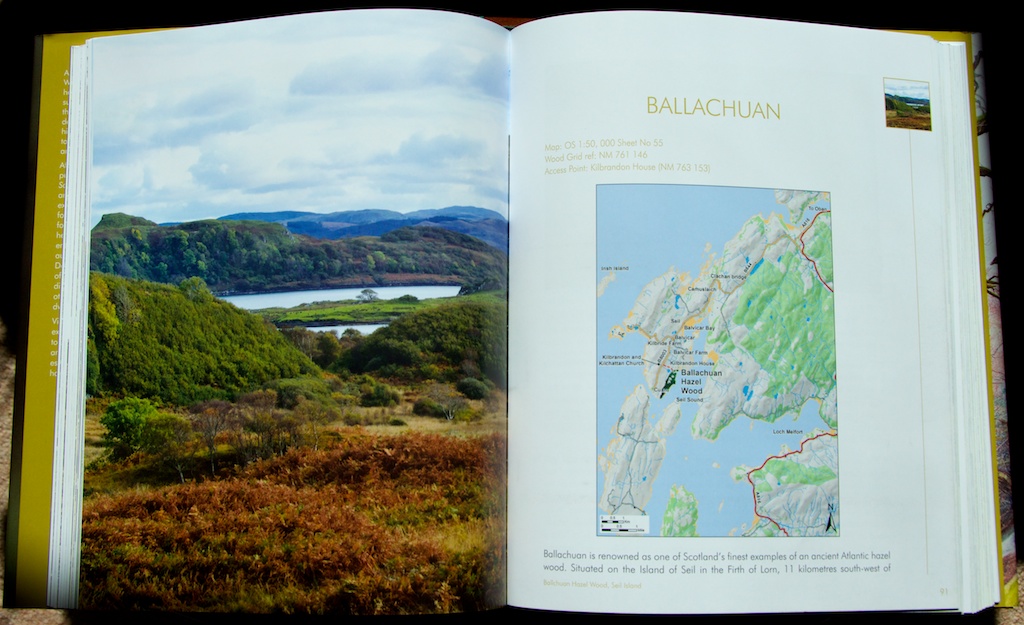

I was interested to read that, in 2005, The Botanical Society of Scotland hosted a symposium which revealed that the Atlantic hazel woods such as those at Ballachuan on Seil Island could be our oldest type of ancient woodland, supporting some of our most threatened plant species. The hazel wood at Ballachuan forms a canopy only a few metres high: “Walking among the myriad of stems, forming strange twisted shapes is an eerie but thrilling experience.” I know how true that is, having walked there myself.

“The River Dart’s name is derived from the Brittonic language meaning ‘river where oak trees grow’.”

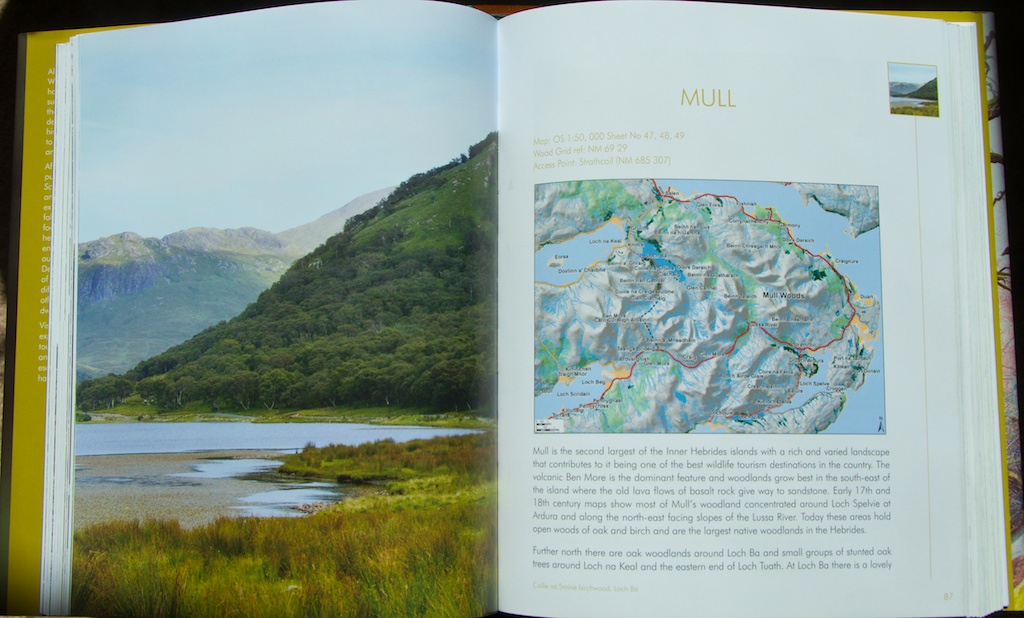

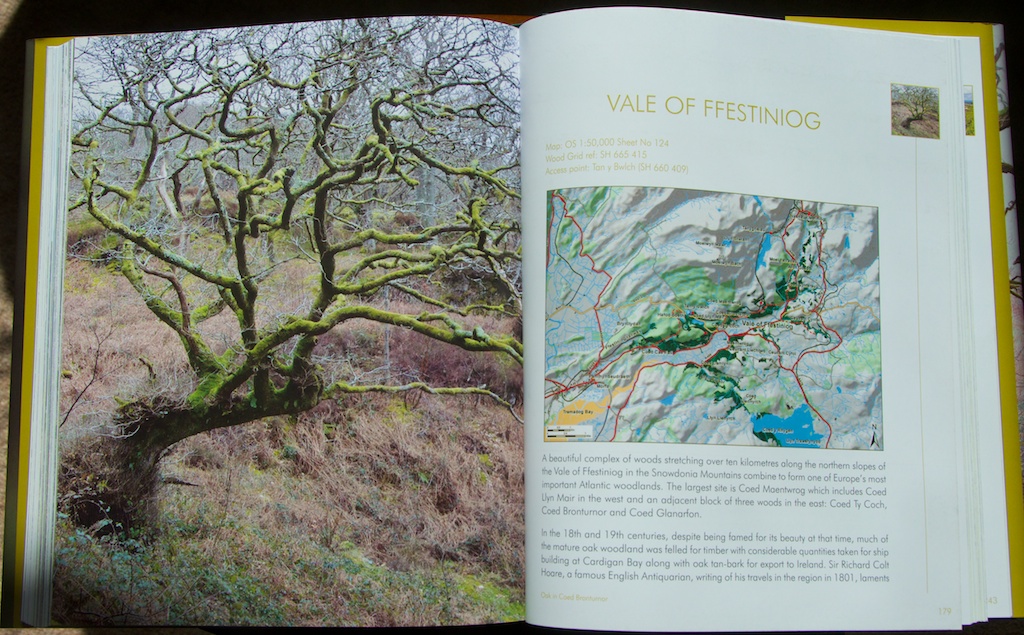

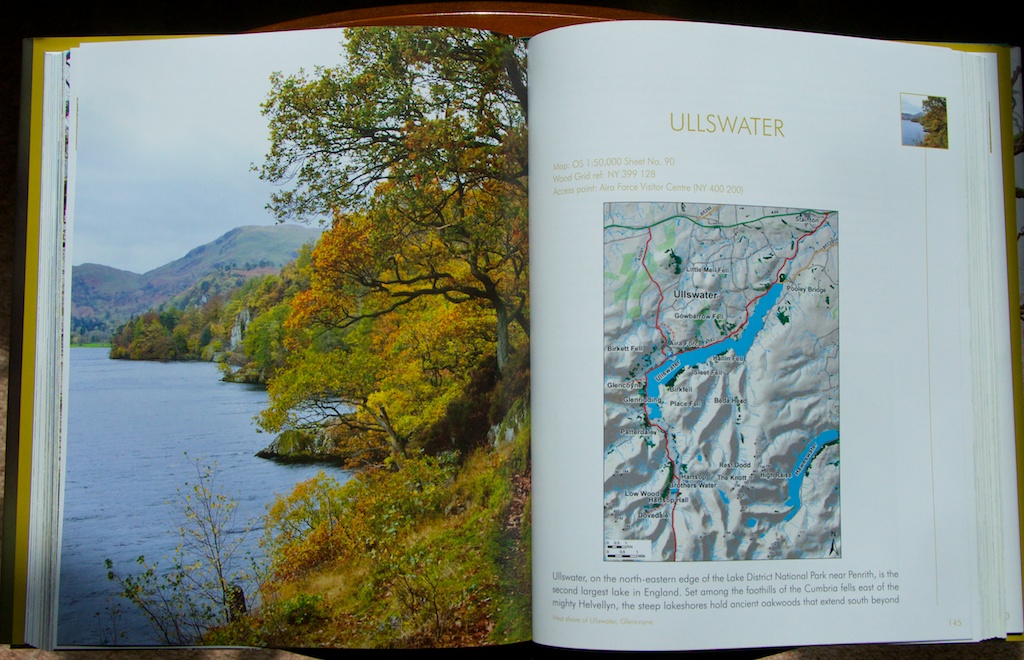

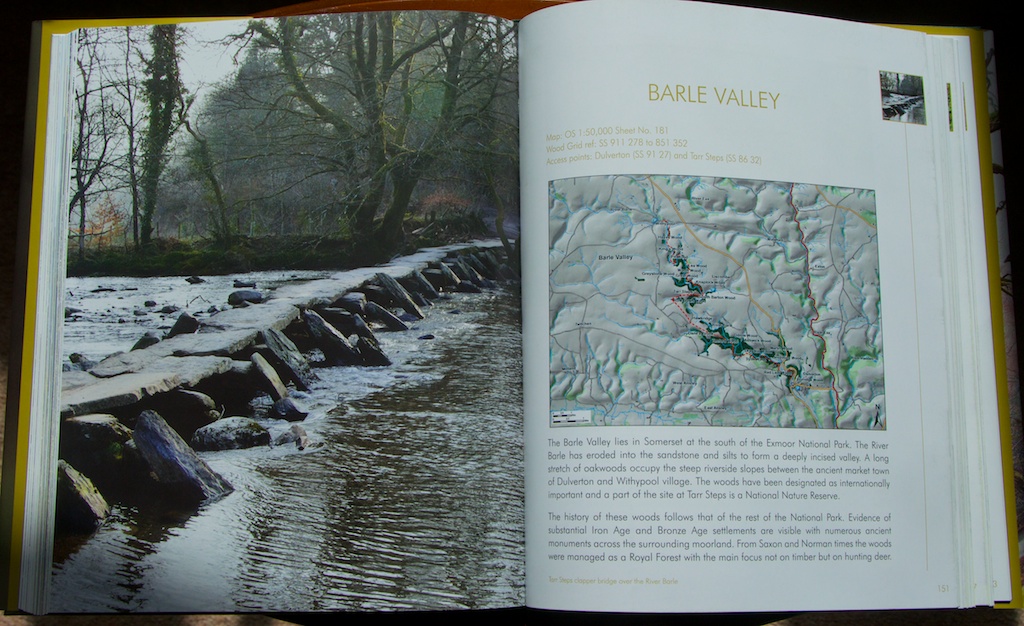

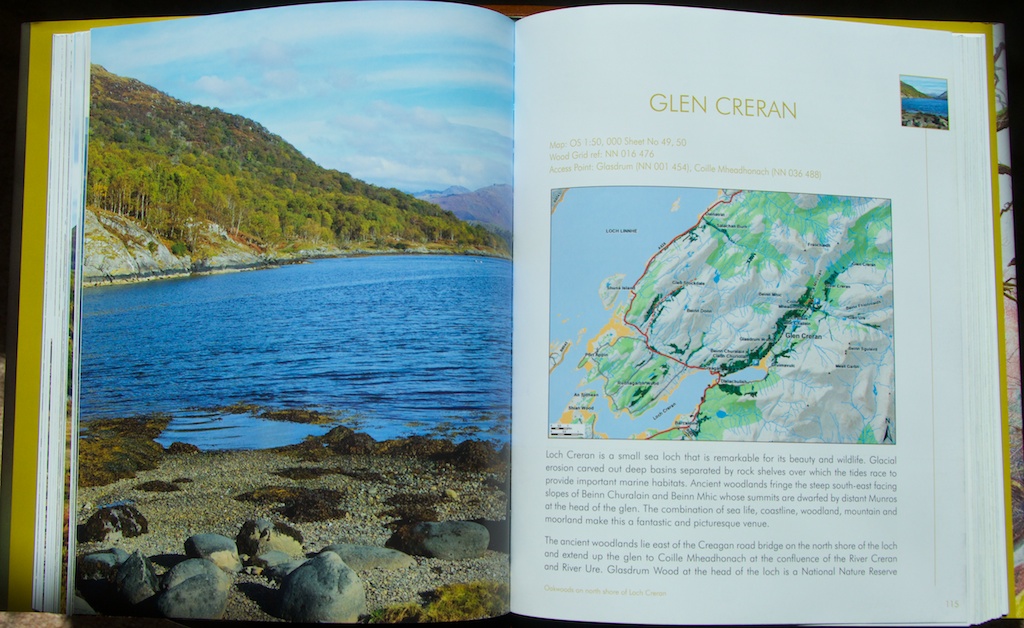

The book is divided into sections, dealing in turn with the rainforests of Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland. Beautiful photographs accompany the text, with occasional pencil drawings by Darren Rees and colour illustrations by Ben Averis. The descriptions offer a not-too-scientific insight into the topography and ecology of the woodland, and a brief history of its use up to recent times. Each woodland has its own chapter, beginning with a map and concluding with travel notes and place names, often with Gaelic translations. As you explore, you will come across fascinating features such as charcoal burners and ancient ‘clapper’ bridges, monasteries and money trees, healing wells and coffin roads, all speaking of lives that have come and gone, knowing and no doubt loving the woods in all their seasons.

“Several of the older alders have rowan trees growing from between forks in the branches giving rise to the term ‘air tree‘ or ‘bird tree’, as a result of the seeds most likely being deposited by birds.”

(The Trossachs)

This is a beautifully tactile book with a silky-feel dust jacket and lovely quality paper. The text is highlighted with headings and captions in moss-green, and the design is simple and clear, with generous margins to the text. The start of each chapter has a full-page photo on its facing page, and this image is echoed as a small icon on the right-hand pages of that chapter – a nice touch. Some general notes on safety and access are given at the back, along with useful websites and suggested further reading.

The temperate rainforests of Britain extend from Sutherland in the far north, through Lochaber and Argyll to the English Lake District, and then through north and west Wales to the valleys of the Bovey and the Dart in Devon; in Ireland, they are dotted more widely, from Glengarriff and Killarney in the south through the beautiful Burren and County Mayo and up to Northern Ireland with the deep glacial valleys of Antrim.

The temperate rainforests of Britain extend from Sutherland in the far north, through Lochaber and Argyll to the English Lake District, and then through north and west Wales to the valleys of the Bovey and the Dart in Devon; in Ireland, they are dotted more widely, from Glengarriff and Killarney in the south through the beautiful Burren and County Mayo and up to Northern Ireland with the deep glacial valleys of Antrim.

I sometimes think that stepping into an ancient rainforest is akin to stepping into a Celtic legend: time and substance become blurred, shadows hold secret life, and our senses open up with a half-forgotten sense of belonging. We would once have felt at home here, known all the sounds, found our way unerringly in the dark, recognised the plants that healed and the ones that spelled danger. Vibrant with life, these woods are time-honoured survivors, carrying a continuous thread that reaches back into the roots of time; and for this reason, any visit is more akin to a pilgrimage than a walk in the park. You can’t help but feel a kind of reverence.

I sometimes think that stepping into an ancient rainforest is akin to stepping into a Celtic legend: time and substance become blurred, shadows hold secret life, and our senses open up with a half-forgotten sense of belonging. We would once have felt at home here, known all the sounds, found our way unerringly in the dark, recognised the plants that healed and the ones that spelled danger. Vibrant with life, these woods are time-honoured survivors, carrying a continuous thread that reaches back into the roots of time; and for this reason, any visit is more akin to a pilgrimage than a walk in the park. You can’t help but feel a kind of reverence.

‘The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland’ is a true travelling companion, informing and inspiring, making you want to linger in every woodland and drink it in through your pores. You get the impression that each has its own distinctive character and atmosphere, and tells its own quiet story. Having explored some of the woods in Argyll and the islands, I now want to venture further north, to Moidart, Morvern and up as far as Sutherland; in fact, just opening this book at random draws me in, with its promise of bluebells and birdsong, crannogs and quiet sea lochs.

The author: Clifton Bain is Director of the IUCN UK Peatland Programme, and his long career as a policy officer with the RSPB arose from a childhood passion for the natural world. This is a follow-up to his earlier book, ‘The Ancient Pinewoods of Scotland’, which I can also recommend.

‘The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland – A Traveller’s Guide’ contains a foreword by Vanessa Collingridge; the photos are supplemented by illustrations by Ben Averis and Darren Rees. Hardback, with 255 pages, it is published by Sandstone Press, priced at £24.99.

Exploring the temperate rainforests of Knapdale…

Take a look at this feature on the ancient oak woods of Taynish

5 Comments

ladyfromhamburg

How interesting! I was really thrilled by your description of the forests and their development over the course of time, Jo!

I made a note of the title and some details as I think it might be one of my next acquisitions. Really great review! Thank you so much for presenting this special book!

Jo Woolf

Most welcome, Michele. It’s a beautifully produced book, dealing with such a unique kind of woodland. I think you will love it!

Lorna

Trees, ancient history and beautiful photographs – I can see why this book appealed to you. 🙂 I know what you mean about feeling a kind of reverence, I’ve felt that sometimes, particularly in the north-west highlands.

Jo Woolf

Haha, spot on, Lorna! 😀 Such an inspiring book, and I want to explore more woods like this now, especially further north.

Pingback: