The island of Gigha

“It was off Gigha that King Hakon’s fleet lay in 1263, when he met the Highland chiefs of Kintyre and the Grey Friars of Saddell.”

‘The Ecclesiastical Antiquities of the District of Knapdale, Argyllshire, and the Islands of Gigha and Cara’ by Capt T P White RE FSAScot, 1867

The ferry to Gigha leaves from Tayinloan on the Kintyre peninsula on the hour, every hour. On a windy morning in early May we boarded the boat at 11 o’clock and set sail to explore an island that we’d not visited before.

The ferry to Gigha leaves from Tayinloan on the Kintyre peninsula on the hour, every hour. On a windy morning in early May we boarded the boat at 11 o’clock and set sail to explore an island that we’d not visited before.

After a 20-minute crossing we disembarked at Ardminish, the main village. Not many folk were about, and we seemed to be the only car that decided to head north on the single-track road which runs in a fairly straight line up the seven-mile length of the island.

Straightaway we were in the midst of farmland, with farmhouses and cottages dotted here and there in the gently undulating landscape. Small patches of willow woodland hugged the slopes, their fresh leaves now a vibrant green, and the verges were lush with wild flowers – bluebells, pink campion and the frilly white umbels of Queen Anne’s lace. To the north-east, white horses flecked a blue-green sea.

Straightaway we were in the midst of farmland, with farmhouses and cottages dotted here and there in the gently undulating landscape. Small patches of willow woodland hugged the slopes, their fresh leaves now a vibrant green, and the verges were lush with wild flowers – bluebells, pink campion and the frilly white umbels of Queen Anne’s lace. To the north-east, white horses flecked a blue-green sea.

I was delighted at how soon we came across a standing stone, right by the side of the road and demanding attention. This is Carragh an Tarbert (the Stone of Tarbert), and it rises to a lop-sided height of seven and a half feet. The top part has been either weathered or shaped into two blunt points, earning it the local name of ‘the Giant’s Tooth’. Other local names include ‘the Druid’s Stone’ and ‘the Hanging Stone’, because according to tradition, criminals would be hanged there, with their heads positioned in the cleft at the top. Nice. I haven’t heard of a standing stone being used in this way before, but in a way it is credible because there must have been few trees on the island big enough to be used as hanging-trees.

I was delighted at how soon we came across a standing stone, right by the side of the road and demanding attention. This is Carragh an Tarbert (the Stone of Tarbert), and it rises to a lop-sided height of seven and a half feet. The top part has been either weathered or shaped into two blunt points, earning it the local name of ‘the Giant’s Tooth’. Other local names include ‘the Druid’s Stone’ and ‘the Hanging Stone’, because according to tradition, criminals would be hanged there, with their heads positioned in the cleft at the top. Nice. I haven’t heard of a standing stone being used in this way before, but in a way it is credible because there must have been few trees on the island big enough to be used as hanging-trees.

A couple of miles further on, we parked the car and walked down through patches of broom and gorse towards two white beaches on either side of a narrow isthmus. It all looked balmy and tropical, which it was certainly not. We kept moving in order to keep warm, turning over pebbles and listening to the gentle wash of the waves. Every now and then the wind would snatch a handful of the powder-soft sand and scatter it across the beach with a dry tinkling sound. Just offshore in the northern bay, a male eider watched us warily. His mate may well have been sitting on eggs nearby.

Vikings on Gigha

It is said that the Norsemen, expertly navigating these waters with their longships, named Gigha ‘gud-ey’, the good isle. There was an age-old conflict between Scotland and Norway over who should control the Hebrides, and in 1263 King Haakon IV of Norway set sail from Bergen with a fleet of at least 120 ships, bent on enforcing his power over the islands with sword and fire:

“No terrifier of dragons, guardians of the hoarded treasure, e’er in one place beheld more numerous hosts. The stainer of the sea-fowl’s beak, resolved to scour the main, far distant shores connected by swift fleets.”

‘The Norwegian Account of Haco’s Expedition Against Scotland’ by the Rev. James Johnstone, 1783

Haakon went ashore at Gigha where he summoned John, King of the Isles, to ascertain whether his loyalty was to him or to Alexander III, King of Scotland. Perhaps with some trepidation, John confirmed that he had indeed sworn an oath to the Scottish king, and offered to return the estates which Haakon had conferred upon him. For several days Haakon tried to persuade him otherwise, and during their negotiations an Abbot from a monastery of Greyfriars arrived, to beg Haakon for the protection of his church, a permission which Haakon sealed in writing. Although it is not specifically named, some historians point to Saddell Abbey in Kintyre as the settlement of Greyfriars in question.

“In return, the monks were able to afford Christian burial to one of the King’s chaplains, named Simon. They interred his body in their church, and ‘spread a fringed pall over his grave, and called him a saint.’ The reference can only have been to the Cistercian monks of Saddell…”

‘A Chronology of the Abbey and Castle of Saddell, Kintyre’, by Andrew McKerral

What a sight it must have been, with the great fleet either out in the Sound or hauled up onto dry land in one of the sandy bays. The king’s vessel “was built entirely of oak, and contained twenty-seven benches for oarsmen. It was ornamented with heads and necks of dragons beautifully overlaid with gold.” (Johnstone)

What a sight it must have been, with the great fleet either out in the Sound or hauled up onto dry land in one of the sandy bays. The king’s vessel “was built entirely of oak, and contained twenty-seven benches for oarsmen. It was ornamented with heads and necks of dragons beautifully overlaid with gold.” (Johnstone)

In 1849 a 10th century Viking grave was discovered on Gigha. While there is no record of human remains, a small stone cist contained a bronze balance and weights, featuring two decorative suspension-pieces in the form of birds.

Congestion on the main road

In the south of Gigha, we went in search of historical sites. I’d remembered reading something about an unusual Ogham-inscribed stone, and was fully expecting it to be positioned right by the roadside like the first one, as if waiting for a bus. It took quite a bit of finding, however. On top of a gorse-covered knoll, overlooking the ruins of Kilchattan chapel, this lichen-encrusted remnant keeps a solitary vigil. It is surrounded by a simple wooden fence, like a wild animal whose power has somehow been lost.

Ogham is an ancient Irish script consisting of linear strokes, and it was used from about the first century AD onwards. It is most common in Ireland, but there are some examples in Scotland and Wales. Opinions differ as to the reasons for its development: some experts believe that it was devised by scholars or druids as a secret means of communication to baffle the invading Romans; others point to the early Christian community in Ireland as the source. An Ogham alphabet has been worked out, but deciphering the inscriptions is an art form in itself, because of the seriously eroded state of some of the carvings.

We examined the stone curiously, disappointed at first because it seemed that the lichen had obscured any visible marks. I thought I could see a group of parallel grooves cut into one edge, and Colin got out his pocket torch to highlight them better. Five short lines, which are obviously only part of a much longer inscription. According to Canmore, Professor K H Jackson has suggested that the symbols meant ‘the son of Coiceile’ and he placed them around the 7th century AD, while Professor R A S Macalister interpreted them as VICULA MAQ COMGINI (Fiacal son of Coemgen), adding that it may be a Scottish inscription under Pictish influence. “Although there are other suggestions as to the meaning of the words, it is a gravestone with the conventional type of inscription giving the name of the deceased and that of his father, and probably dates from the earliest settlements of the Scots in Dalriada.” (Canmore)

Professor John Rhys, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1901, reveals that the stone fell (or was pushed) on two separate occasions in the 1800s, and now stands a short distance from its original site. On the first occasion, which was around 1845, nearby quarrying activities disturbed the stone, and it fell down the hillside; on the order of the local laird, it was dragged back up the hill by two horses and a sledge, and put back in the same spot. About 20 years later it fell again, possibly with the help of some local lads, and was carried back up on the shoulders of a party of men. Rhys quotes some contemporary accounts that were conveyed to him, recalling that the stone was once much taller, but that a piece about two feet long had broken off the top at some unknown date. One report, supplied by a resident called Neil Graham, suggests that this piece was was built into a pigsty belonging to James MacDonald, who lived close by; but another story was told by an old man named Angus Macvean, describing how, when he was a boy, some men dug into a watch-cairn in the north of the island and found a piece of stone about 28 inches square with some marks on it. This was later re-buried in the cairn. “He said they seemed to know where to look for it, and found it, but what the markings were he never knew.”

Professor John Rhys, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1901, reveals that the stone fell (or was pushed) on two separate occasions in the 1800s, and now stands a short distance from its original site. On the first occasion, which was around 1845, nearby quarrying activities disturbed the stone, and it fell down the hillside; on the order of the local laird, it was dragged back up the hill by two horses and a sledge, and put back in the same spot. About 20 years later it fell again, possibly with the help of some local lads, and was carried back up on the shoulders of a party of men. Rhys quotes some contemporary accounts that were conveyed to him, recalling that the stone was once much taller, but that a piece about two feet long had broken off the top at some unknown date. One report, supplied by a resident called Neil Graham, suggests that this piece was was built into a pigsty belonging to James MacDonald, who lived close by; but another story was told by an old man named Angus Macvean, describing how, when he was a boy, some men dug into a watch-cairn in the north of the island and found a piece of stone about 28 inches square with some marks on it. This was later re-buried in the cairn. “He said they seemed to know where to look for it, and found it, but what the markings were he never knew.”

I love the way local folklore continues to weave stories around itself, like a knitted scarf that’s never finished. To enhance the mystery, it seems that at one time there may have been two more standing stones in this locality. Duncan Colville, in ‘Notes on the Standing Stones of Kintyre’ (Soc. of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1930), refers to three stones which once stood in a straight line: one in Achadh-a’Charra (the Field of the Pillar); one on top of Cnoc-a’Charra, (the Hill of the Pillar); and “farther to the north-east, on a higher hill, there was a cross which fell some years since, and was broken.”

I’ve tried to ascertain which of these is the surviving Ogham stone, but without definite success.

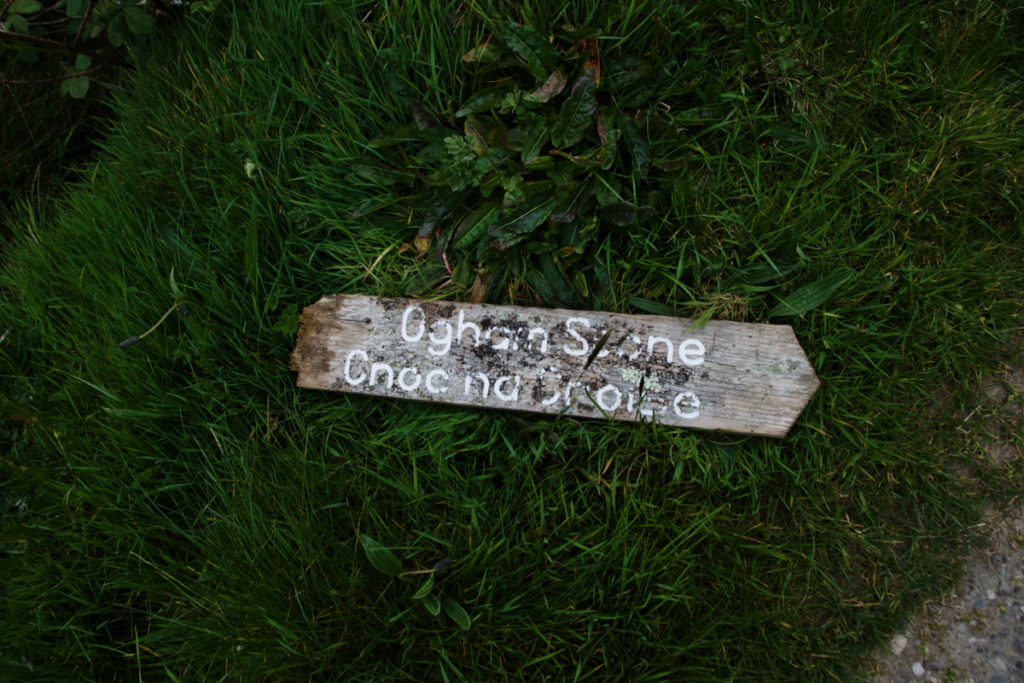

Cnoc na Croise: A wooden signpost pointing to the low hill where the Ogham stone stands. Cnoc na Croise means ‘hill of the cross’.

Cnoc na Croise: A wooden signpost pointing to the low hill where the Ogham stone stands. Cnoc na Croise means ‘hill of the cross’.

Kilchattan chapel is dedicated to St Cathan, an early Irish missionary-saint. The surviving structure dates from the 13th century, but there is likely to have been a much older Christian presence, especially with the ‘Kil’ or ‘cille’ element which denotes a hermit’s cell. An information sign told us that, at the lower end of the graveyard, there was once a holy well dedicated to St Cathan, but its position has now been lost.

We wandered around the old graveyard, taking in some of the gravestone inscriptions and feeling heart-struck, for what must be the hundredth time, at the untold stories of parents who lost most or all of their children at a young age. Some surnames kept re-appearing, among them MacNeill, MacDonald and Galbraith, but many stones were far too weathered to be legible.

Gravestone of Malcolm McNeill, who died in 1855, erected by his sons Donald Lachlan and Malcolm McNeill. The grave is inside the chapel itself.

The MacNeills of Gigha

Gigha is the heartland of Clan MacNeill. When he died in 1449, Alexander MacDonald, Lord of the Isles, endowed Torquill MacNeill with lands in Gigha, and thus began a succession of Lairds which ended in 1530 with the murder of Neill MacNeill by Allan Maclean, a son of the infamous Lachlan Cattanach Maclean of Duart. Since there were no male MacNeill heirs, Gigha then became the focus of much feuding and violence between the Macleans and the MacDonalds. The MacNeills of Taynish and MacNeills of Colonsay held it in 1631 and 1780 respectively, and in the 19th century it again passed out of the clan. In 1944 it passed to Sir James Horlick, who established a 54-acre garden at Achamore. In 2002 the island was the subject of a community buy-out, and continues to support a small but thriving population.

“There are MacNeills still in Gigha, amongst the 165 inhabitants.” (gigha.org.uk)

By the time we caught the return ferry, the rain was setting in. So much for spring… May, so far, has felt much more like March. But already the nights are barely dark, with a glow in the north-west until after midnight and woodcock flying moth-like around the woods. Such nights brought the Norsemen, ‘summer wanderers’, looking for new land and thirsty for battle. Maybe one evening I’ll see those gilded dragons glinting in the moonlight.

By the time we caught the return ferry, the rain was setting in. So much for spring… May, so far, has felt much more like March. But already the nights are barely dark, with a glow in the north-west until after midnight and woodcock flying moth-like around the woods. Such nights brought the Norsemen, ‘summer wanderers’, looking for new land and thirsty for battle. Maybe one evening I’ll see those gilded dragons glinting in the moonlight.

Sources & reference:

- Isle of Gigha website

- ‘The Ecclesiastical Antiquities of the District of Knapdale, Argyllshire, and the Islands of Gigha and Cara’ by Capt T P White RE FSAScot, from Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1867

- ‘The Gigha Ogam’ by Professor Rhys, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 1901

- More about Ogham script at History Today

- Canmore database:

- Carragh an Tarbert

- Ogham stone

- Kilchattan chapel

- Viking burial

- ‘The Norwegian Account of Haco’s Expedition Against Scotland, 1263’ by Rev. James Johnstone

- ‘Notes on the Standing Stones of Kintyre’ by Duncan Colville, Soc. of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1930

10 Comments

davidoakesimages

Another great expedition….. I have bookmarked the page for a more leisurely read later with a coffee (or maybe a wee dram)

Jo Woolf

Thank you, David! We enjoyed it very much. There’s more to explore on Gigha as well, particularly Achamore Gardens which we didn’t visit, although we glimpsed some of the rhododendrons in flower.

greg-in-washington

Thank you for sharing this adventure on Gigha and your wonderful photos. One can imagine that time hasn’t passed there with exception of a few modern things shown.

Jo Woolf

You’re most welcome, Greg, and I’m glad you enjoyed it. Yes, there was a real feeling of peacefulness there – it was like stepping back in time, although there are modern facilities when you look for them, and the restaurant was excellent too.

Sandra

Wonderful! I felt I was there exploring with you. Thank you, Jo 🙂

Jo Woolf

That’s lovely to know – thank you, Sandra!

Stravaiging around Scotland

I also haven’t heard of criminals being hanged on standing stones but there’s a stone on the edge of Loch Rannoch called the Clach a’ Mharsainte where a travelling merchant is supposed to have accidentally hanged himself when his pack slipped off the stone and he was strangled by the strap.

http://www.stravaiging.com/history/ancient/site/clach-a-mharsainte

Jo Woolf

Oh no!! What a horrible accident!! But an interesting story – thank you! I thought it was an unusual use of the stone myself, but these stories must come from somewhere!

Thom Hickey

Fascinating. I’ll pack my bags!

Regards Thom

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Thom! I hope you get to visit Gigha sometime soon – it’s a little gem of an island.