Diarmuid and Grainne: a boar hunt and a tragic love story in Glen Lonan

The frost was still crisp on the grass when we ventured across the field in Glen Lonan in search of the Strontoiller stone circle.

It was one of those blissful autumn mornings, so perfect that you know it’s going to be short-lived; so you try to drink in all the blue sky and inspect every sparkling rime-fringed leaf, while all the time your footsteps are crushing some of the magic beneath them.

We had no problem finding the stones, even though Strontoiller must be one of the least noticeable stone circles I’ve ever seen. It measures about 60 feet in diameter and is made up of 30 or so rounded boulders, all of which are less than waist height. They are all very firmly earth-fast, and some of the lower ones lie hidden beneath dense cushions of grass; only if you push them with your foot can you tell a stone is there.

I felt as if I needed to crouch down to fully explore and appreciate this circle, and to capture the sunlight streaming between the stones. Suddenly, it became a land of giants, with a forest of reed stalks and waving seedheads. I wonder if children played here? I’m sure they did!

I felt as if I needed to crouch down to fully explore and appreciate this circle, and to capture the sunlight streaming between the stones. Suddenly, it became a land of giants, with a forest of reed stalks and waving seedheads. I wonder if children played here? I’m sure they did!

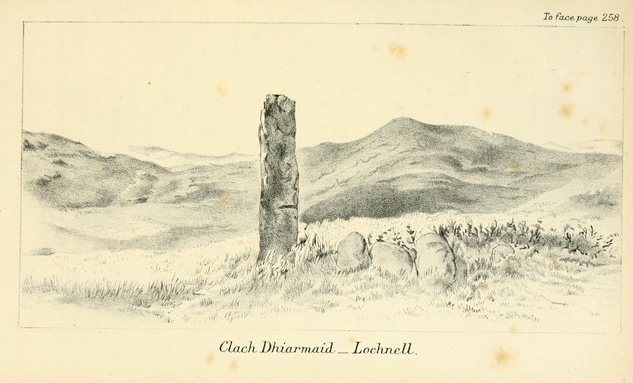

A couple of hundred yards across the field, almost on the edge of the road, is a much more conspicuous landmark. Clach na Carraig, otherwise known as Diarmuid’s Pillar, is a massive standing stone that rises to a height of over 12 feet; from one angle it looks like an arm with a clenched fist reaching defiantly out of the cold ground. It seems almost square-sided, and the rough surface is pitted with little crevices that allow mosses and lichens to flourish. It certainly has an arresting presence, and is possibly one of the largest single standing stones I’ve seen.

A couple of hundred yards across the field, almost on the edge of the road, is a much more conspicuous landmark. Clach na Carraig, otherwise known as Diarmuid’s Pillar, is a massive standing stone that rises to a height of over 12 feet; from one angle it looks like an arm with a clenched fist reaching defiantly out of the cold ground. It seems almost square-sided, and the rough surface is pitted with little crevices that allow mosses and lichens to flourish. It certainly has an arresting presence, and is possibly one of the largest single standing stones I’ve seen.

Close enough to be touched by the stone’s shadow is a small cairn consisting of a handful of low boulders. It doesn’t look that significant, and in fact the first time I visited the standing stone I overlooked the cairn completely. Some of the stones are so embedded in the ground that they are almost hidden, but you can still see that it is roughly circular in outline, and quite compact.

Close enough to be touched by the stone’s shadow is a small cairn consisting of a handful of low boulders. It doesn’t look that significant, and in fact the first time I visited the standing stone I overlooked the cairn completely. Some of the stones are so embedded in the ground that they are almost hidden, but you can still see that it is roughly circular in outline, and quite compact.

In this timeless place you can trespass easily into the realm of legends. And the door has been left open, thanks to the diligence and curiosity of a Victorian gentleman…

In this timeless place you can trespass easily into the realm of legends. And the door has been left open, thanks to the diligence and curiosity of a Victorian gentleman…

During the 1870s, the historian Dr R Angus Smith visited the cairn beneath Diarmuid’s Pillar, and counted a total of 13 stones. He and his companions cleared away some brambles and attempted an excavation to see if it contained a burial, but they found no trace of one. While he was absorbed in this activity, Dr Smith was approached by a local woman in some anxiety, because she assumed that they were “lifting Diarmuid.” He was quick to assure her that they were not… and he was fascinated, too, because this conversation proved to him that the old stories connected with this place were still alive.

This cairn, according to local tradition, is the burial place of Diarmuid (also Diarmaid or Diarmid), a hero of Irish legend. The pillar or standing stone also takes his name, as it marks the spot where he lies. The woman who spoke to Dr Smith was repeating a story that stretches back to the time before written manuscripts, when the old tales were handed down by word of mouth and cherished because they defined the people who continued to tell them; and this story, of Diarmuid and Grainne, was one of the best-loved of all.

In the story, a man named Fionn mac Cumhaill was betrothed to Grainne, the daughter of Cormac mac Airt, the High King of Ireland. Renowned for his strength and skill, Fionn was the leader of a legendary band of hunters and warriors known as the Fianna. But when Grainne met Fionn at a banquet hosted by the king at Tara, she saw that he was an old man, older than her father, and she had no liking for him at all. Instead, her eyes were drawn to one of Fionn’s faithful young warriors, and during the betrothal feast she quietly questioned one of her father’s druids about his identity. “Who is that sweet-worded man,” she asked him, “with the dark hair, and cheeks like the rowan berry, on the left side of Oisin, son of Fionn?” She learned that he was Diarmuid, son of Donn and grandson of Duibhne; his foster-father, Aengus Óg, had given him a deadly sword named Móralltach, which left no blow unfinished, and he also wielded spears whose wounds could not be healed. Aside from being a formidable warrior, Diarmuid was blessed (or cursed) with a love spot known as the ‘Bol Sherca’ on his forehead, which had the magical effect of making every woman fall in love with him.

Grainne, it seems was already under his spell. Acting quickly, she instructed her maidservant to bring her the great golden cup that would hold enough liquid for nine times nine men to drink. She filled it with wine “that had enchantment in it”, and directed her servant to offer it first to Fionn, then to the King and Queen, and to the rest of the assembled company with the exceptions of Diarmuid, the warriors Oisin, Osgar and Caoilte, and Diorraing the Druid. When she saw that everyone else was asleep, Grainne spoke.

“Will you take my love, Diarmuid, son of Duibhne, and will you bring me away out of this house to-night?”

“I will not,” said Diarmuid. “I will not meddle with the woman that is promised to Fionn.”

Grainne must have been expecting an honourable refusal, because she responded by putting Diarmuid under druid bonds, a form of oath which constrained him to do her bidding whether he wished it or not. Anxiously Diarmuid consulted Oisin, Osgar and Caoilte, and reluctantly they advised him that he had no choice but to comply. Finally, he asked for the druid’s counsel. “I tell you to follow Grainne,” said Diorraing, “although you will get your death by it, and that is bad to me.” Obviously druids did not beat about the bush.

Diarmuid and Grainne fled from Tara, knowing that Fionn and his warriors would soon be on their trail. Grainne insisted that they abandon their horses and cross a river, so as to leave no scent for Bran, Fionn’s hound, to follow. Diarmuid was by no means reconciled to his fate: he tried unsuccessfully to reason with Grainne, while quietly dropping a trail of unbroken bread for Fionn to find, as a sign that his bride’s virtue remained intact. In the middle of Doire-da-Bhoth, the wood of the two huts, Diarmuid made Grainne a bed from soft rushes and the topmost branches of birch trees.

Back in Tara, the warriors Oisin, Osgar and Caoilte were in an exceedingly awkward position. They joined Fionn in the chase, but did their best to protect Diarmuid and Grainne so that they could evade capture. When they came to the wood, they quietly commanded Bran to run to Diarmuid and warn him of their approach, which they knew she would do because she loved him as she loved her own master. Meanwhile Diarmuid’s foster-father, Aengus Óg, who had somehow got word of the drama, appeared as if by magic (of course, they were all magicians!) and smuggled Grainne out of the wood, unseen beneath his cloak. To avoid a battle, Diarmuid leaped over Fionn’s warriors “on the staves of his spears”, which sounds if he would have made a champion pole vaulter. He then fled westwards, finding Aengus and Grainne ensconced in a cosy cabin with a boar roasting over a blazing fire.

Diarmuid and Grainne’s wanderings, and the trials that they endured, makes for a very long and complex story. The tale is well told by the Irish folklorist Lady Gregory in ‘Gods and Fighting Men’ (1905).

Towards the end of their saga, the pair take shelter in a cave by the sea. Despite her advances, Diarmuid has still not made love to Grainne. He reproaches her: “I left my own people that were brighter than lime or snow; their heart was full of generosity to me, like the sun that is high above us; but now they follow me angrily, to every harbour and every strand… O Grainne, white as snow, it would have been a better choice for you to have given hatred to me, or gentleness to the head of the Fianna.” But Grainne is unashamed: “Your blue eye is dearer to me than his strength, and his gold and his great hall; the love-spot on your forehead is better to me than honey in streams; the time I first looked on it, it was more to me than the whole host of the King of Ireland.” And after that night, the trail that Diarmuid leaves for Fionn to follow is of broken bread.

Diarmuid settles with Grainne in a land far from Tara, and Grainne bears him four sons and a daughter. But one night he hears the baying of hounds, and insists on going to investigate, despite Grainne’s premonition of doom. On the summit of Beinn Gulbain Diarmuid is surprised to meet Fionn, alone as if waiting for him. Fionn challenges him to slay a boar that has many times evaded the spears of the Fianna. Almost as an afterthought, he adds that Diarmuid is under a bond placed by his foster-father, Aengus, that he should never go hunting boar because it will cost him his life. Fionn has Diarmuid in a trap, and he knows it.

Diarmuid grimly ignores the warning. He grapples with the boar and kills it, but not before the beast has savaged him grievously. As he lies dying, Diarmuid reminds Fionn that he can save his life, if he wishes: he has a gift of healing, and anyone who is offered a drink from the palms of his hands will be young and well again, no matter what ails them. Conveniently, a spring of pure water is only nine steps away. Fionn gathers some water in his hands, but it slips through his fingers before he can return to Diarmuid; he tries a second time, and fails. On the third attempt he sees that he is too late: Diarmuid has died.

When Grainne hears of Diarmuid’s death, she lets out a long, pitiful cry that brings all her people running to her in alarm. She shares the news with them, and in turn they give three great heavy cries that are heard “in the clouds and in the waste places of the sky.” Diarmuid’s body is carried on a golden bier to the sorrowing Aengus Og, for burial at Brú na Bóinne.

“O Diarmuid,” laments Grainne, “it is a hard bed Fionn has given you, to be lying on the stones and to be wet with the rain… your blue eyes to be without sight, you that were friendly and generous and pursuing. You were a champion of the men of Ireland… you were my happiness, Diarmuid.”

There’s a lot more to this story! It’s the kind that was told countless times around hearths and camp fires, and probably embellished upon with each telling. There are different variations, but the general theme is the same.

And you might be wondering why these stones in Glen Lonan are connected with Diarmuid and Grainne, when all the drama is supposed to have taken place on the other side of the Irish Sea, and Diarmuid himself is said to lie sleeping beneath one of Ireland’s greatest prehistoric landscapes in County Meath. The answer is that the legend seems to have spread across the water and attached itself to several places in Scotland. Dr Angus Smith, the historian who excavated the cairn, was convinced of the validity of Glen Lonan as an additional setting for the story. In a paper submitted to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1873, he discusses several convincing place-names in the vicinity of the stones:

“Tobair nam bas toll, the well of the hollow hand or leaky palms, where the water was obtained which might have restored Diarmid. The version here is, that the water was to be brought in the hands of the most beautiful women; but the road was rough and the day warm, so that it was all lost before it reached the sick man.

The hill Tor an Tuirc, the boar’s hill. Boar, not in the plural, Mr Clerk [a local historian] says; so that it was one particular boar.

Ault ath-Carmaig. Grainne was said to be a daughter of Cormac; but then St Cormac was famous in Argyle; a choice of derivation.

Drum na Shealg – The hunting height.

Sron t-Soillear – The nose of the light, the exit from the wood.

Mr Clerk tells me also of Bar Guillean, after, he thinks, Cuchullin [another hero of Irish legend] who seems to be remembered in the district.”

As for Beinn Gulbain, Dr Smith remembers that, on his visit to Glen Lonan, he overheard a farmer advising a shepherd to take his sheep up Ben Gulbain, “so here is the classic name in common use.” I must admit that I cannot find a Ben Gulbain in Glen Lonan, but it may be a name that has been lost. However, there’s a hill called Ben Gulabin in Glen Shee in Perthshire, and a number of features marked on old maps – Leabaidh an Tuirc, the boar’s bed, and Loch an Tuirc, the boar’s loch – suggest that the story of Diarmuid and Grainne exists here too.

Dr Smith mentions several other Scottish places connected with the legend of Diarmuid and Grainne, including Glen Lyon; but there is something about Glen Lonan, an atmosphere that he could sense over a hundred years ago, and it still lingers there today. And, of course, at the other end of Loch Nell lies a serpent mound and a chambered cairn known as the ‘Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn’. I’m beginning to wonder if people passing through there ever emerge again into the same world.

Diarmuid’s Pillar and cairn, from ‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’ by Dr R Angus Smith

Reference and reading:

‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’ (1875) by Dr R Angus Smith

‘Gods and Fighting Men’ (1905) by Lady Gregory

‘Legends of the Celts’ (1989) by Frank Delaney

‘Descriptive List of Antiquities near Loch Etive’ by R Angus Smith, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 10th February 1873

‘Excavation of a Cairn at Strontoiller, Lorn, Argyll’ by J N Graham Ritchie, 1967 (RCAHMS)

Canmore: Strontoiller stone circle

Canmore: Diarmuid’s Pillar

Canmore: Strontoiller Cairn

Photos © Colin & Jo Woolf

Interesting note: The cairn was excavated again in June 1967 and a full report was prepared by Dr J N Graham Ritchie of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. In the process, some of the kerb stones that had fallen over were eased into their original positions, and a couple were seen to dovetail neatly into each other. Ritchie felt that their gently decreasing heights had been engineered with great care. White quartz chips had been scattered around their bases. Ritchie says: “A small quantity of cremated bone was recovered from the central area, both in the back-filling of Smith’s pit and in the undisturbed basal layer of cairn material beyond it.” This suggested to him that it was indeed a burial cairn. Detailed examination of the bone fragments was inconclusive, but there was no evidence of more than one individual, who was likely to have been an adult. A layer of burnt material, including distinct patches of charcoal, was found beneath the stones and gravel of the cairn material, and this layer extended beneath the kerb stones; Ritchie speculated that this may represent the remains of a funeral pyre.

4 Comments

Deb Vallance

I appreciate your stories, observations, enthusiasm and pictures. Thank you for your efforts and for sharing.

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Deb! It’s such a pleasure to share them. I’m just entranced by these old stories. 🙂

Ashley

A wonderful story and I read it whilst listening to Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2 in C minor!

Jo Woolf

Wow – very fitting! That’s one of Colin’s favourite pieces of music, and he often paints to it!