An old story of Craignish

I’m always being reminded that pretty much every rocky outcrop, every patch of woodland and every bay in this part of Scotland has a story attached to it. This wet and windy weather isn’t great for exploring, so I’ve been dipping into a collection of old folk tales that were transcribed by Lord Archibald Campbell in the late 19th century and published in five volumes under the charming title of ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’. Being out of copyright, they have been digitised by the National Library of Scotland and are available online.

The first volume has a section called ‘Craignish Tales’, and since Craignish is where we live, I’ve been reading these with particular interest. Even the titles are alluring – for example, ‘The Hoof-prints of Scota’s Steed’, ‘The Fair-haired Lady of Craignish’, and ‘The Stag-haunted Stream’ . History seeps into legend, with tales of love, lust, honour and revenge, and of course plenty of feuding, skirmishing and blood-letting.

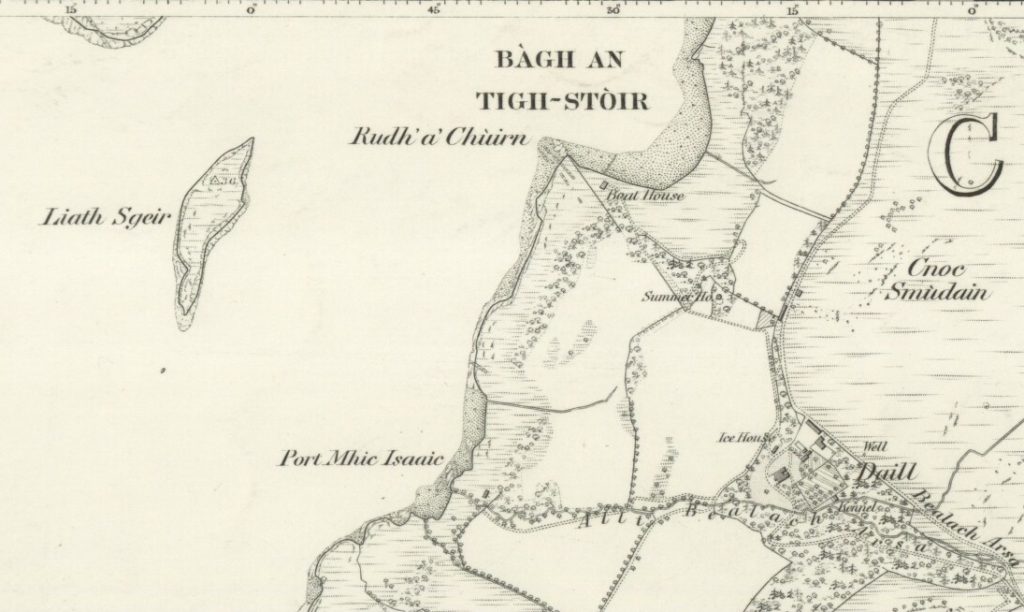

One of the stories relates to a man named McIsaac or Mhic Iosaic, who is remembered in the place-name of Camus Mhic Iosaic or McIsaac’s Bay (now shown on maps as Port Mhic Isaaic). This lovely bay looks west towards the islands of Jura and Scarba. We walk down there often, as it’s a fabulous place to sit and watch the sunset.

There is no date offered for this story. All I can say is that the events appear to have happened after the Craignish estate came into the possession of the Campbells, which according to the author was “about the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th century.” Here it is, as it appears in the collection.

Raonull og Chreiginnis (Young Ranald of Craignish)

Young Ranald of Craignish was sent by his father to ‘Airidh-Sceòdinnis’, the district between Kilmartin river (Sceòdag) and Loch Craignish, to be fostered by McIsaac of Largie (Learga Mhic Iosaic). McIsaac was noted for his strength and bravery, and also for his expertness in military exercises, as they were then known. These manly and soldierly qualities recommended him to Campbell of Craignish as a suitable person to be entrusted with the fostering of his son Ranald.

When Ranald’s period of fosterage was completed he left Largie, accompanied by his eight foster-brothers (comh-dhaltan), the sons of old McIsaac. They took the road to Ormaig, on the south side of Loch Craignish, and thence turned to the right with the intention of following the path which leads round the loch into Craignish. They had not proceeded far when they entered the wood of Ormaig, which was then infested by a notorious freebooter and his companions. This worthy was nicknamed ‘Am Marsanta Fada’, or Long Merchant; fada, from his length of limb and tallness of stature, and marsanta, from his habit of occasionally sallying forth from the wood disguised as a travelling-packman, and thus visiting the surrounding country for such information regarding the movements of the inhabitants as he could turn to his own account.

On one of these visits he ascertained the time of Ranald’s return home, and the route which he intended to take; at once he resolved to waylay the latter and make him prisoner, with the intention of extorting a heavy ransom for his release. Hastily returning to the wood, he took up a convenient position for carrying out his scheme, and there awaited the approach of his intended victim. When the moment for action arrived, he and his men sprang from their hiding-places and rushed with wild impetuosity on the brave McIsaacs. The latter had barely time to form a circle round their foster-brother when the outlaws were down upon them.

A desperate encounter then followed, from which none of the combatants on either side escaped unhurt. The ‘Long Merchant’ and his band were slain to a man, and one-half of the McIsaacs lay dead on the field. The other half, with young Ranald, were more or less severely wounded; only one of them all, ‘Calum mòr’, was in a condition to return to Largie. This poor fellow left the field wounded and bleeding, and with great difficulty succeeded in reaching his father’s home. Old McIsaac, then blind and bed-ridden, recognising his son’s voice, said:

“Have you come, my son?”

“Yes, father, I have come,” was the reply.

“Where did you leave your foster-brother and your brothers?”

“I left them on the battle-field.”

“Come here, my son, and kiss me, seeing that you have returned to me in life.”

The latter, suspecting no evil, moved towards his father’s bed; but his mother, who watched her husband, suddenly cried, “Fly, fly! He has the dirk (biodag) in his hand.” The son stepped back immediately, but not a moment too soon. The old man, following the sound of his son’s retreating footsteps, darted his dirk after him, accompanying the action with the remark, “You are not a son like your father, else you would not have been here while your foster-brother and brothers lie dead on the field.” (“Cha mhac thu mar an t-athair air-neo cha bhiodh tusa an so, agus do chomh-dhalta agus do bhraithrean ’n an luidhe anns an àraich.”)

The dirk, fortunately, missed the mark, explanations followed, and the old man’s indignation was appeased. Men were immediately sent with a sled (càrn) to bring the wounded home.

When young Ranald recovered, he returned to Craignish, and, in gratitude to the McIsaacs for their fidelity, his father gave Calum mòr McIsaac, already mentioned, a farm on the Craignish lands. The name of the farm has been forgotten, but there is a bay on the farm of Daill still known as Camus Mhic Iosaic, or McIsaac’s Bay.

Extract from ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition‘ Argyllshire series, Vol. I (1889) by Lord Archibald Campbell

An entry in the Argyll OS Name Books (1868-1878, Vol 3, Craignish) confirms that Port Mhic Isaaic is a small bay about half a mile south of Rudha Chuirn, and that its name means ‘Isaac’s son’s port’.

Path to Ormaig

Loch Craignish from Ormaig

Port Mhic Isaaic

Ordnance Survey, 6″ 1st edition, Argyllshire sheet CXXXVIII, published in 1875 (survey date 1871-2) via NLS maps

Photos copyright © Jo Woolf

10 Comments

Finola

Great place name story. McIsaac is a big name in Nova Scotia – wonder if this is where they came from.

Jo Woolf

That’s interesting! Yes, could be!

Ashley

I would imagine that no matter where we walk on these islands there are many stories, mostly untold. No matter where we walk in the landscape, we tread on the lives of our ancestors. We should walk slowly and give thanks for their part in our lives.

Jo Woolf

That’s a lovely thought, and I totally agree!

davidoakesimages

Great story, no matter if true or false, adds to the romance of Argyll. 🙂

Jo Woolf

Very true! There’s no shortage of these tales – the landscape just seems to grow them!

davidoakesimages

Its that rich fertile ground beneath all those wet dripping trees along the Loch shore 🙂

Jo Woolf

Haha, you’re right!

Bob Hay.

Interesting to read that a sled was used Jo. I’ve been pondering a question for a while re the method used to transport rocks and timber building those castles in the West. Sleds seem more simple, rugged and practical than the building and upkeep of wheeled carts where no roads existed.

Jo Woolf

Yes, very true! Wheels need a decent track, or they’re no use at all. Many castles around here were close to the sea so I’m guessing building materials were shipped as close as possible and unloaded on the shore. But as for the hilltop duns, I can imagine a sled, pulled by men or horses, would be a good solution.