Glengarrisdale and Maclaine’s skull

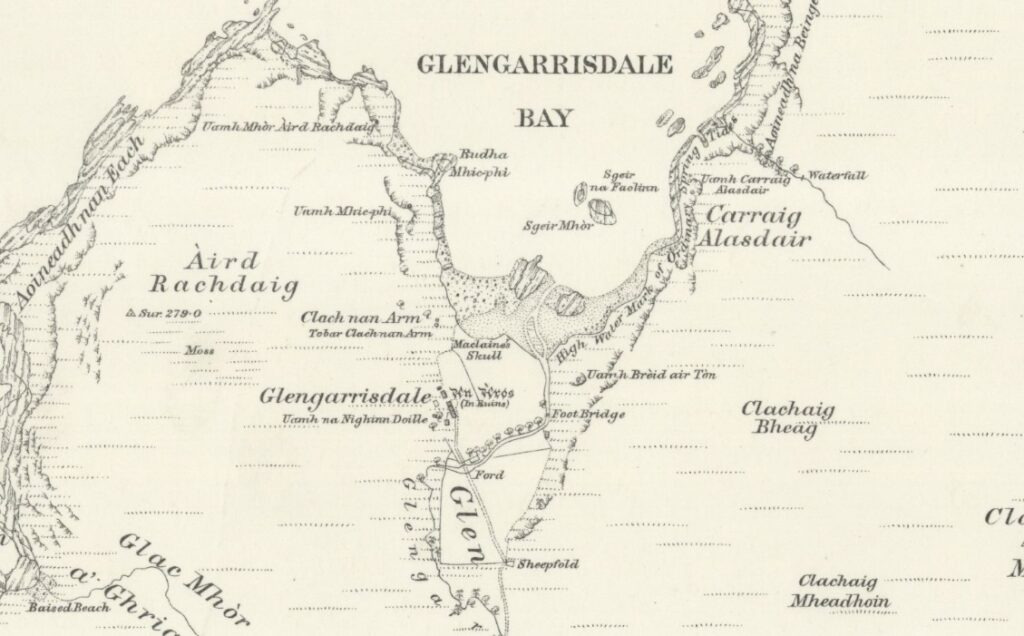

I’m going to start this post with a map, because it’s central to the story. It’s an old one, part of the 6” OS map of Argyllshire from 1881 (sheet CXLVII, surveyed in 1878).

Map courtesy of National Library of Scotland

It shows Glengarrisdale Bay on the Isle of Jura. If you look at the central part (click to enlarge), you will hopefully spot a place-name that’s a little out of the ordinary. ‘Maclaine’s Skull’ could easily be a curious geological formation that’s been given a fanciful title. But it’s not. It is a real human skull. The reason it’s marked on the map is because it has been there for over three centuries: the owner, a Maclaine (we don’t know his Christian name) lost it in 1647. Attached to it is a blood-soaked story of a clan feud, a massacre, and revenge – and what makes it even more interesting is that the details are preserved in some of the other place-names in Glengarrisdale.

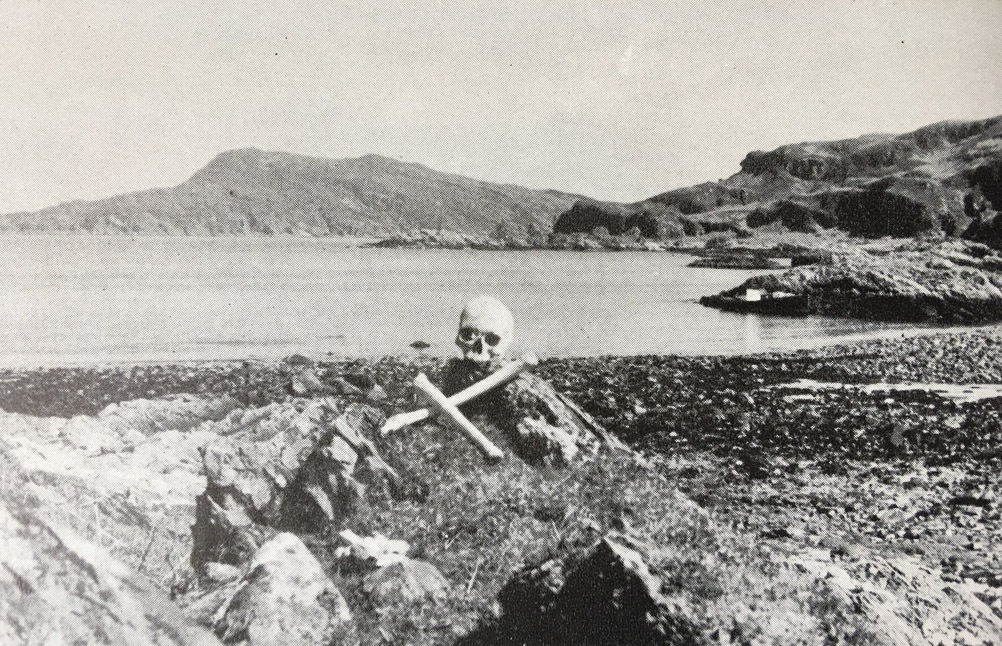

Now, I should say right now that the skull is no longer in its designated spot on the map, which shows it right on the shore, on a rock just above the high tide mark. It was last photographed there in 1972, but by 1976 it had vanished. However, a local tradition claims that, whenever it disappears, it always comes back. It may just be well hidden.

This is the story of how it got there, according to Archibald Campbell who included it in ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’ (1889):

This is the story of how it got there, according to Archibald Campbell who included it in ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’ (1889):

In the mid 17th century, Glengarrisdale was in the possession of the Maclaines of Loch Buie on the Isle of Mull. In good Highland spirit, there was a long-standing feud between the Maclaines and the Campbells of Craignish, just across the water on the mainland. Sometime in 1647 the Campbells heard on the grapevine that the stronghold of the Maclaines at Glengarrisdale (‘An Aros’ on the map, in Gothic font) was weakly garrisoned. Nurturing an old grievance and bristling for a fight, they took to their boats, crossed the Sound of Jura and landed at a place that Archibald Campbell calls ‘Knock-an-tavil’. (If this is on the east coast, it could possibly be Cnoc an Taillir near Lealt).

Walking quickly over the hills, the Campbells reached Glengarrisdale where they spied the Maclaines enjoying a contest of ‘putting the stone’ (another version says that they were swimming). Whichever image you prefer, the important point was that they were off-guard and had placed their swords on a convenient rocky knoll which forever after was called Clach-nan-Arm or ‘the rock of the weapons’. A nearby spring is named Tobar Clach-nan-Arm or ‘the spring by the rock of the weapons’.

Creeping low until they were between the Maclaines and the rock, the Campbells launched themselves on the unsuspecting men and killed them all in cold blood – except for one man, named McPhie. He managed to swim to a headland called Rudha Mhic-phi (McPhie’s Point) and hid himself in a cave called Uamh Mhic-phi or McPhie’s Cave. The next day, he signalled to some Maclaines on board a passing birlinn, who picked him up, heard his story and quickly sailed over to Mull for reinforcements.

Piling into Glengarrisdale and hell-bent on revenge, the outraged Maclaines found that the Campbells had left the scene of the massacre and were on their way home. Whether they were still on Jura at this point is debatable, but Archibald Campbell clearly assumes that they were. He says that the Maclaines went after them, got ahead and then waited in ambush at the foot of a slope called Creachan-Dubha. On seeing them, the Campbells tried to put up a fight but owing to the steep gradient they couldn’t engage in combat properly and “their feet and legs were hewn off by the [Maclaines] with their battle-axes.” Afterwards the Maclaines went back to Glengarrisdale and buried their dead beneath cairns which the writer says were still visible in the late 19th century. All, that is, except one, whose skull remained above ground for the next 370 years. Why, we’ll probably never know.

And it wasn’t just a skull, but parts of a skeleton that were unburied. In the late 1800s the geologist Sir Archibald Geikie was cruising around the island in a steam yacht with his friend Henry Evans and a Miss Campbell of Jura. Miss Campbell told him the story of the battle and revealed that a skeleton of one of the Maclaines was still lying on the shore. Geikie expressed disbelief, so they landed in Glengarrisdale so that he could see for himself. The shepherd, who lived in the little bothy, came out to greet them:

“Miss Campbell asked him where the skeleton was, and he pointed to an overhanging piece of rock about a hundred yards from where we were standing. On reaching this spot, we found a few rough stones lying at the foot of the low crag. These the man, stooping down, gently removed, and below them lay the bleached bones. We took up the skull, which was well formed and must have belonged to a full-grown man. A piece of bone about the size of a half-crown had, evidently by the sweep of a claymore, been sliced off the top of the skull, leaving a clean, smooth cut. This wound, however, had not been considered enough, for the head had been cleft by a subsequent stroke of the weapon, and there was the gash in the bone, as sharply defined as on the day the deed was done. We gently replaced the bones, with the stones above them, and there they remain as a memorial of ‘battles long ago.’” (Sir Archibald Geikie, ‘Scottish Reminiscences’, 1904)

This is the kind of story that immediately makes you want to hurry over to Glengarrisdale and see it for yourself – and yes, to check the coastal rocks and crags for any lingering skulls. However, getting there is more difficult than you might think. To reach Jura by ferry, two sailings are required – one to Port Askaig on Islay, and another across the narrow Sound of Islay to Feolin Ferry on Jura. Once there, the only road on Jura (called the ‘Long Road’) stops just over half-way up the east side of the island. Then you’re left with a long and demanding hike over rough, boggy terrain to reach the uninhabited west coast.

The only other option is to arrive by boat, timing it carefully to coincide with slack tides through the Corryvreckan and taking a dinghy so that you can get ashore. This is the means by which we explored Glengarrisdale a few days ago, and I’ve got to say that it is one of the wildest, most idyllic places I’ve ever seen.

The day was bright, virtually windless, with a calm and sparkling sea. As Farsain slipped through the Corryvreckan just a few gentle eddies were whirling, as if someone was lazily stirring the water from below. The dark cliffs and crags of Jura rise straight from the sea, punctuated at intervals by secret sandy bays that are as tempting as they are difficult to access. On the hills above, red deer grazed. Jura has long been known for its deer: its name is said to derive from the Old Norse dýr-ey, meaning ‘deer island’.

The day was bright, virtually windless, with a calm and sparkling sea. As Farsain slipped through the Corryvreckan just a few gentle eddies were whirling, as if someone was lazily stirring the water from below. The dark cliffs and crags of Jura rise straight from the sea, punctuated at intervals by secret sandy bays that are as tempting as they are difficult to access. On the hills above, red deer grazed. Jura has long been known for its deer: its name is said to derive from the Old Norse dýr-ey, meaning ‘deer island’.

Splashing ashore in Glengarrisdale, we took a look around and breathed in the quiet magic. A short expanse of sand gives way to lines of seaweed, patches of pale rounded pebbles and tussocky grass. The Glengarrisdale river, shallow, peaty and ice-cold, flows out to sea from the heart of the glen. To one side, backed by a low rocky knoll, is a tiny white-washed building that was once a croft and is now a walker’s bothy, and the ruins of other buildings stand nearby. From the top of a rugged promontory two wild goats stared at us with huge round eyes.

We made our way over to the east side of the bay, where a long vertical gash in the rock face is the shadowy entrance to a cave. This feature is marked on modern OS maps as ‘Maclean’s Skull Cave’ – presumably because the skull resided in here at some point in its long history. We went inside, gazing up into the high ‘roof’ and peering into natural cavities. We were surprised to find that the cave had another entrance at the back, making it fairly light inside but very draughty.

We made our way over to the east side of the bay, where a long vertical gash in the rock face is the shadowy entrance to a cave. This feature is marked on modern OS maps as ‘Maclean’s Skull Cave’ – presumably because the skull resided in here at some point in its long history. We went inside, gazing up into the high ‘roof’ and peering into natural cavities. We were surprised to find that the cave had another entrance at the back, making it fairly light inside but very draughty.

Near the cave entrance is a big lump of rock with a pronounced overhang – no doubt another natural feature that has been carved by the sea. Was this the “overhanging piece of rock” below which Geikie found the bones? Looking around at the landscape, I tried to bear in mind that sea levels have risen and fallen dramatically over thousands and millions of years as glacial periods have come and gone, and the features that now stand high and dry on Jura’s coast were once scoured by the waves.

Near the cave entrance is a big lump of rock with a pronounced overhang – no doubt another natural feature that has been carved by the sea. Was this the “overhanging piece of rock” below which Geikie found the bones? Looking around at the landscape, I tried to bear in mind that sea levels have risen and fallen dramatically over thousands and millions of years as glacial periods have come and gone, and the features that now stand high and dry on Jura’s coast were once scoured by the waves.

We crossed the river by some fairly randomly placed stepping stones, skirted the bothy and explored the western shore, where some weird and fantastically-shaped crags bisect the beach. To eat our picnic lunch, we sat on a rocky outcrop with a flattish grassy top. Were we sitting on Clach-nan-Arm, the rock of the arms? It looked like a convenient place, but there were many other possibilities. Then, in the warm afternoon sun, we picked our way across slopes and boulder fields to McPhie’s Point, where we found McPhie’s Cave. This one was quite deep and had plenty of uncomfortable crevices into which a person could secrete themselves, should they wish. The floor was thick with goat and deer droppings, out of all proportion to the number of goats and deer that we’d seen. I’m guessing they’ve been going in there for shelter for more centuries than we can imagine!

We crossed the river by some fairly randomly placed stepping stones, skirted the bothy and explored the western shore, where some weird and fantastically-shaped crags bisect the beach. To eat our picnic lunch, we sat on a rocky outcrop with a flattish grassy top. Were we sitting on Clach-nan-Arm, the rock of the arms? It looked like a convenient place, but there were many other possibilities. Then, in the warm afternoon sun, we picked our way across slopes and boulder fields to McPhie’s Point, where we found McPhie’s Cave. This one was quite deep and had plenty of uncomfortable crevices into which a person could secrete themselves, should they wish. The floor was thick with goat and deer droppings, out of all proportion to the number of goats and deer that we’d seen. I’m guessing they’ve been going in there for shelter for more centuries than we can imagine!

Above: a candidate for Clach-nan-Arm, which has intriguing remains of low stone walls built into the side of it

Above: McPhie’s Cave and (below) the view from inside

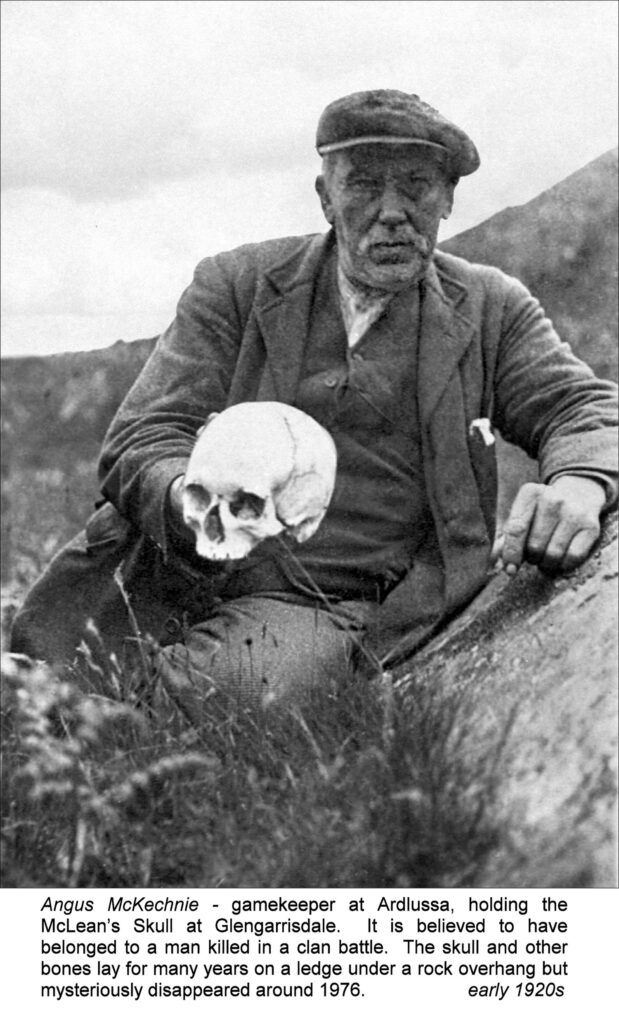

I walked over to the bothy on the way back and had a peek inside. No one was there, and the two small rooms were just as the last guests had left them – simply furnished, with lots of half-burned candles and empty whisky bottles. From reading other blog posts, including one published in 2010 by hill-walker Peter Edwards on Writes of Way, it seems that the bothy’s last permanent resident was Kate Johnson, a crofter who lived there during the 1940s. Peter’s blog is well worth reading for his own experiences of staying there, and the history of the place. He includes in his post a photograph from the 1920s (shown below) of gamekeeper Angus McKechnie holding Maclaine’s skull.

Below: The skull in its former resting place, included in ‘Hebridean Islands’ by John Mercer (photographer unknown)

The crag immediately behind the bothy is said to be the site of An Aros, the stronghold which the Maclaines left unguarded back in 1647, with disastrous consequences. According to surveys listed on Canmore, in 1932 it was possible to make out two irregular enclosures, but in the 1970s there were “no identifiable remains of the supposed castle…” The old map shows a cave close by, named as Uamh na Nighinn Doille – ‘the cave of the blind girl.’ I didn’t find it, and I can’t yet find any story attached to it. A good reason to return!

I’d also read that a nearby group of trees is supposed to mark an old settlement, so I went to have a look. The lowest courses of stone walls are still visible on the ground, but whether these were sheep pens or a dwelling it’s impossible to say. I was more interested in a flat area, perhaps about 30 feet or more across, which appeared to have been paved with rounded stones, now half-buried in the grass. There seemed to be a distinct entrance with a path leading to it, also paved or cobbled. What was it for? These random things survive, and lacking any further evidence we try to make sense of them! As I stood and pondered, a cuckoo – the first of the year – called from somewhere way up in the glen.

I’d also read that a nearby group of trees is supposed to mark an old settlement, so I went to have a look. The lowest courses of stone walls are still visible on the ground, but whether these were sheep pens or a dwelling it’s impossible to say. I was more interested in a flat area, perhaps about 30 feet or more across, which appeared to have been paved with rounded stones, now half-buried in the grass. There seemed to be a distinct entrance with a path leading to it, also paved or cobbled. What was it for? These random things survive, and lacking any further evidence we try to make sense of them! As I stood and pondered, a cuckoo – the first of the year – called from somewhere way up in the glen.

After a few fleeting hours in Glengarrisdale, we didn’t want to leave. But the absence of humans, after all, is what makes this place so special. We are privileged to have experienced it at all. There will be other times, and other tides, and meanwhile in my mind at least I can go back there and sit on the stones and gaze around.

There are wonderful natural and historical sites all the way down the west coast of Jura, and it seems that each one has a legend attached to it. We’re planning further trips! Meanwhile our grateful thanks to Tony and Julie of Farsain Cruises, and to Karen, Darren and John for their company on a glorious day.

Reference and further reading:

- Canmore: Maclean’s Skull Cave

- Canmore: An Aros

- National Library of Scotland

- Lord Archibald Campbell, ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition‘ (I, Argyllshire) (1889)

- Sir Archibald Geikie, ‘Scottish Reminiscences‘ (1904)

- Scotland’s Places – Argyll OS name books, 1868-1878

- Peter Edwards, ‘Peace, Love and Glengarrisdale Bothy‘, Writes of Way, October 2010

- John Mercer and Susan Searight, ‘Glengarrisdale: confirmation of Jura’s third microlithic phase’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 116, 1986

- John Mercer, ‘Hebridean Islands‘, 1974

12 Comments

MOIRA GOODMAN

Wonderful interesting article Jo with superb pictures. Thank goodness the clans no longer do battle with each other having McLeans and Campbells in my family as well as McKinlays, McNaughtons and McKays. Jura looks like the perfect place to get away from the madness that has taken over the world.

Jo Woolf

It was fantastic, Moira! We’re looking forward to discovering more of Jura, and some of the other islands too. Yes, thank goodness the clans no longer battle each other! Sounds like you’d have a job deciding whose side to be on too! Good to hear from you and hope you’re all well. x

Euan Cameron

A very interesting read. Thank you. Just to say that I went there with my dad back in the 1960s. We found the skull and some bones. I took a photograph with my Kodak Instamatic camera.

Jo Woolf

Oh, how exciting! I’d love to see a pic if you’d be willing to send me one (you can email me at jo@thehazeltree.co.uk) I’m glad to know that people have found the skull and remember it – I’d like to think it’s still there somewhere!

Finola

An excellent adventure indeed, and what an amazing landscape. It’s got everything – remoteness, unearthly beauty and lots of stories!

Jo Woolf

Yes, it really has! We are so looking forward to exploring more of it. I just love knowing these wild places exist!

john speirs

great article jo and it was such a lovely day out thanks to you and colin for inviting me to join the trip

Jo Woolf

Thanks, John – it was fun, wasn’t it? Looking forward to the next one!

Ashley

Wonderful, Jo, as usual! Splendid pictures too. The older I grow the more I want to run away to somewhere like this but of course I don’t run like I used to! ? Perhaps I could walk there ?. As I have only 3% Scottish genes I wouldn’t be intruding or stepping on any clans toes!?

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Ashley! Oh yes, we often dream of living on our own island! We saw a number of lovely little bothies, including one on Scarba. That’s a good thought about the Scottish genes, or lack of them – not sure where I’d be on that one, with Scott as my family name!

Karen Reader and Darren Thomas

That’s another wonderful adventure that you have described so well, Jo. Our thanks to you both for inviting us to come along with you and also to the new team at Farsain Cruises. It was a brilliant day!

Jo Woolf

Thank you! It was so nice to have you both along! What a fabulous day, I still love looking at the pics. Looking forward to the next one!

It was so nice to have you both along! What a fabulous day, I still love looking at the pics. Looking forward to the next one!