Stronefield: a mill, an abandoned settlement, and a lost Jacobite’s cave

Right at the bottom of Kilmory Knap, past the beautiful little chapel and the white sands of Kilmory Bay, the wooded hillsides and quiet pebbly bays hold a wealth of secrets that speak of long-lost human haunts and memories.

Poring over an OS map, it’s possible to see scattered settlements, now in ruins and abandoned, their identity preserved only in place-names. Stronefield is one of them. A handful of buildings and enclosures are marked about half-way up a slope overlooking the valley of Abhainn Mhor, a burn which empties out into Loch Caolisport. A ruined mill lies a mile or so to the south-west. Having found a couple of short articles about it in an old issue of ‘The Kist’, we decided to go and have a look.

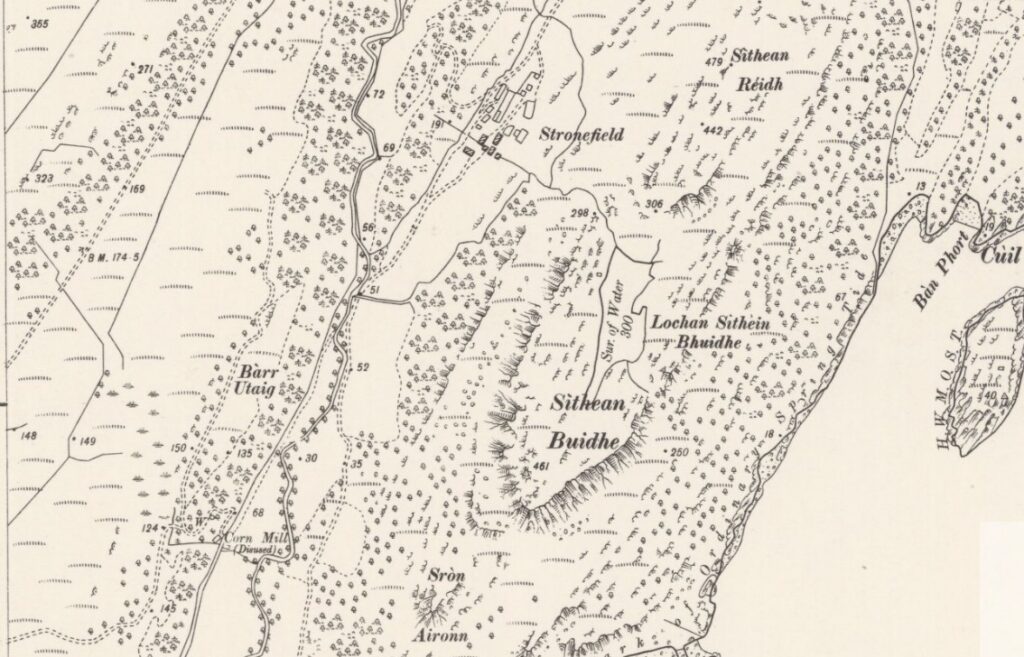

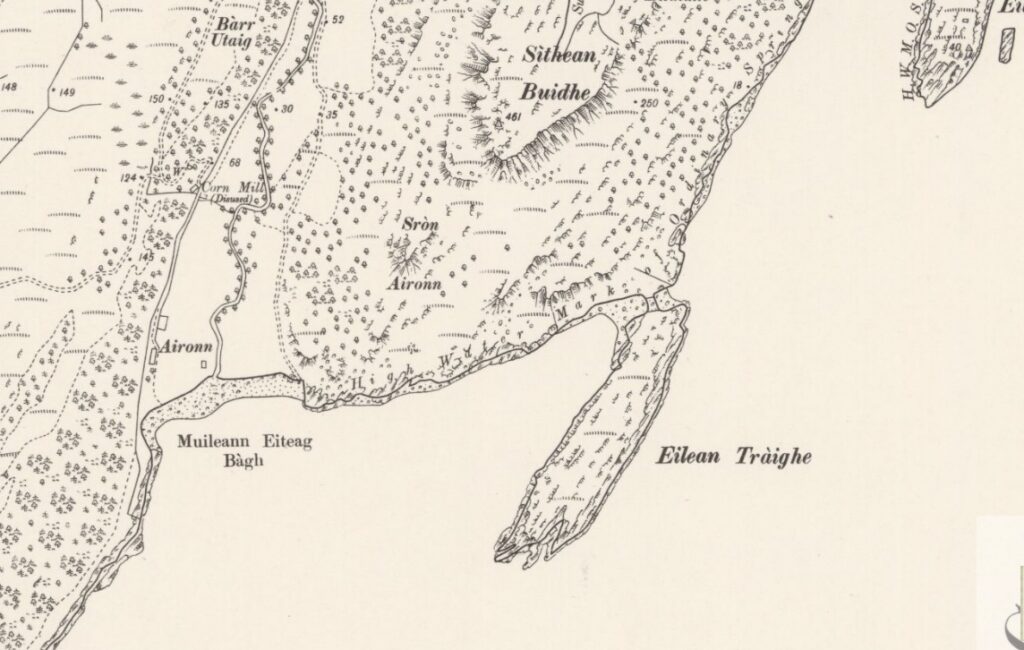

Above and below: 6″ OS Map from 1900, showing Stronefield, the hill of Sìthean Buidhe and its lochan, and Aironn corn mill and settlement. Maps courtesy National Library of Scotland.

A farm track, deep and well-worn with centuries of use, winds its way over the rough rocky prominence of Cnoc Mòine before plunging down into a wooded glen. We set off on a fine clear morning in June, with the sun promising later heat; the sheep which were grazing on the moor were already seeking the shade of trees. As we started to descend into the woods, a couple of cuckoos flew across our path and into the trees, calling loudly. A pair, no doubt, and the female would soon be eyeing up the nest of an unsuspecting warbler or pipit, if she hadn’t found one already.

A farm track, deep and well-worn with centuries of use, winds its way over the rough rocky prominence of Cnoc Mòine before plunging down into a wooded glen. We set off on a fine clear morning in June, with the sun promising later heat; the sheep which were grazing on the moor were already seeking the shade of trees. As we started to descend into the woods, a couple of cuckoos flew across our path and into the trees, calling loudly. A pair, no doubt, and the female would soon be eyeing up the nest of an unsuspecting warbler or pipit, if she hadn’t found one already.

Above: old buildings at Balimore, our start point

From the high branches of an oak tree we could hear – and eventually see – a lovely little wood warbler, singing its heart out among the leaves. Wood warblers aren’t that common; our first view of one was at Taynish earlier this year. This one was in full flow and it was lovely to take time and listen to its distinctive, repeated notes. Another one was answering, further off. Late spring is always such an energised and magical time, when the trees themselves seem to resonate with birdsong.

Wood warbler

When we reached the mill, it was hard at first to distinguish the old masonry from the trees. The shade here was so deep that everything was cast in a greenish light. Trees are reclaiming the crumbling stonework, both from outside and within, and the ground beneath was lush with buttercups, speedwell, the tiny yellow stars of tormentil and the last few bluebells. The water that cascades down the glen no longer powers the water wheel, which has long gone although its position is still evident.

This is Aironn Mill, an old corn mill named after the small settlement (now abandoned) just a short distance away on the shore; however, it’s also known as Stronefield Mill, from the settlement further up the glen. Canmore reveals that it originally belonged to the township of Balimore; in the hearth-tax schedule of 1693, a mill here is mentioned as being part of the Knap estate. The surviving building is thought to date from the late 1700s, when the estate was owned by the Campbells of Inverneill. By 1869 it had fallen into disuse.

Above: the wall where the waterwheel was fixed

In his article in ‘The Kist’, (1974), F S Mackenna observes that an archway in the north gable was blocked up at some stage to allow for the construction of a drying kiln. He adds: “The very width of this archway seems to prove its former use by carts, although how they negotiated such a steep road seems rather a mystery… In the 1830s the thatch began to be replaced by a covering of woven hair, similar to the hair-cloth floors used in drying hops in the Kent oasthouses in my youth.”

In the same issue, Henry Rogers writes that water was brought to the mill by an artificial lade some two thousand yards from the burn; this lade filled a hollow which was dammed with stone and turf, and from this hollow a further lade was cut, passing under the track and down to the mill. In this way, the water supply could be regulated as any excess water would just spill over the top of the dam.

Above: the lade; below: a grinding stone

Turning north-east, we crossed the burn, which was low in water, and made our way up the glen, stopping for a few minutes to cool down in the shade of a birch wood. The remains of a stone building were visible further up the hill, and as we approached, more buildings came into view. Impossible to say how many houses were once here at Stronefield, or how many people might have lived in them. The low rubble walls of livestock pens can still be traced on the ground, some adjoining the houses and some a short distance away.

In the Argyll OS Name Books of 1868-1878, Stronefield is mentioned as having “three small farm houses and outbuildings, the property of […] Campbell Esq., of Inverneill.” Among the named authorities confirming the spelling of this and many other local place-names are Duncan McKellar and Alexander McAlpine, both of Stronefield, and Archibald McMillan of Aironn (spelled ‘Airon’). Apart from anything else, this gives a strong clue to the names of the families who last resided here. At that time, Aironn had “a couple of cotters’ houses.” On the OS map of 1900, six buildings at Stronefield are shown as roofed (at least 10 are unroofed), while at Aironn there no roofed buildings and the corn mill is marked “disused”. Sìdhean Buidhe (‘yellow hill’), an outcrop to the south-east, is described as “a remarkably tough rocky hill.”

Looking around, I wondered what life was like here: it looks idyllic now, but in the 1800s and before it must have been hard to scrape a living off the land.

And it seems that, in the 1700s, there were other challenges too – either for local residents or travellers from further afield. Just over the other side of the ridge we’d noticed a ‘Jacobite’s cave’ marked on Canmore’s map, with a brief description:

Cave about 150′ up cliff; concealed entrance, long ledge, hearth, stone seats, escape chute and cleft down which food is said to have been lowered from above by herdsmen. Traditionally used by refugees waiting for shipment to France. (M Campbell and M Sandeman, 1964)

We couldn’t resist trying to find the cave, so from Stronefield we headed roughly south-east, skirting Lochan Sìthean Bhuidhe and pushing through a hillside of hummocky heather and dwarf willow. Over the crest of the ridge, the slope fell more steeply in a tumble of large boulders down to Loch Caolisport; we could hear more cuckoos calling from across the water.

Above and below: Lochan Sìthean Bhuidhe

Heading up from the lochan

First view of Loch Caolisport

Could we find the cave’s ‘concealed entrance’? Among a whole hillside of jumbled rocks on a difficult gradient? The answer, I’m afraid, is no. We checked out a number of crevices that might – just – have accommodated one person, if they were prepared to wedge themselves in at an angle; but there was nothing large enough to contain a hearth or stone seats. What made it even trickier was that everything was overgrown.

Any Jacobites in there?

Any Jacobites in there?

Maybe it’s a good thing that it was impossible to find; the place was well chosen. In the 18th century the folks around here would have known their landscape intimately, well enough to walk over it in the dark; they’d have known the best places to hide, probably from having played here as children. I can’t help wondering though, who might have taken refuge in the cave, and whether they made it safely to France. Who did they leave behind? And did they ever come back? So many untold stories.

The boulders gave way to a lovely birch wood, but we were still high above the shore of Loch Caolisport and needed to get down. On an overhanging bluff, we stood and gazed at the tantalising beach below us. The ‘slope’ that we thought would give us easy access to the shore turned out to be a 100-foot drop down an uncomfortable-looking cliff. So gorgeous, so frustrating! But we’d already battled our way through some difficult terrain, and didn’t fancy turning back. We decided to get down there as best we could. I’m pretty glad no one was there to witness our technique and our running commentary, but anyway within about 15 minutes we had safely deposited ourselves on the shore. With hindsight, I totally agree with Messrs McKellar, McAlpine and McMillan that Sìdhean Buidhe is “a remarkably tough rocky hill.”

Above and below: the birch wood… and trying to get out…

Now what?

Above and below: the cliff we climbed down (some of those boulders are loose!)

It was then just a matter of rounding the headland, so after dabbling a little in the warm sea we picked our way across the beach boulders to Muileann Eiteag Bàgh (which F S Mackenna translates as ‘white-pebble-mill-bay’). An old name, and still very fitting – it’s banked with rounded white pebbles, perhaps the remnants of a raised beach, and the old mill lies less than half a mile away. From there, we walked across a field and rejoined the track that leads up from Aironn Mill, through the oak woods where the wood warblers were still singing, and then out across the open fields where the puddle-hollows in the track were baking hard and dry in the afternoon heat.

Above and below: the beach of Eilean Tràighe

Muileann Eiteag Bàgh (above and below)

Looking back up towards Stronefield from the beach

The remains of a row of cottages at Aironn… perhaps one is the former home of Archibald McMillan

A stiflingly hot car awaited us. Kilmory beach was busy so we kept going, glad of the breeze through the windows. At home, we got the maps out again. Where is the Jacobite’s Cave? We have a better idea now – we might have gone a little too far down the ridge. In late autumn, when the bracken and other plants have died down, we might take another look.

Reference & reading:

- F S Mackenna, ‘Stronefield Mill’, and Henry Rogers, ‘Stronefield Mill’, The Kist (vol. 7, 1974) (PDF)

- Canmore: Aironn Mill

- Canmore: Stronefield

- Canmore: Jacobite’s Cave

- Argyll OS Name Books, 1868-1878

- Maps sourced from National Library of Scotland

Photos copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf

22 Comments

Linda Wilson

An area I know well and love, beautifully described and photographs wonderful. Thank you

Linda Wilson

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Linda! Glad you enjoyed it. We loved our day there, even though it was a bit challenging! There are lots more places down that way I want to investigate.

Ashley

With lovely weather your trip must have felt almost perfect! Thank you for this wonderful post ??♂️

Jo Woolf

We did enjoy it, especially with the bird sightings and the flowers! I remember it was a long hot slog back to the car! But well worth it for the places we found and the amazing views. Thanks, Ashley! 🙂

georgie

I go up there every summer and have my own secret path to stronefield- it is a lovely village. I even met the last inhabitant of the village! Never managed to find the cave though, which is a shame, as it would be very interesting.

Jo Woolf

How amazing that you met the last inhabitant! When was that, I wonder? At some stage we might find the cave, in which case I’ll certainly write a blog post! 🙂

Theresa Frank-Schengili

How many of these poor people will have packed their kist? I enjoy reading your posts every time.

Jo Woolf

Exactly – you wonder where they have all gone, and where their families are now! Thank you very much, Theresa.

Finola

I love the idea of a Jacobite’s cave – how features in the landscape get invested with history.

Jo Woolf

I know – and it makes you wonder how many other caves were used for such purposes, and have been forgotten about!

davidoakesimages

No cave…after all that effort. I guess they would have ensured it was well hidden and of course time makes changes. But then again, maybe another trip is needed. The Chapel is as far as we have ventured, so maybe we need to go that bit further. 🙂

Jo Woolf

Yes, haha! But it’s a good reason to go back. The road does go on quite a bit after the chapel – we went that way earlier in the summer and there were loads of red deer in the fields.

davidoakesimages

OK you have convinced me ?

Jo Woolf

Good, haha! 😀

Kevin Gore

Lovely article as usual, with beautiful photo’s. “oast houses in kent”, seams we both came from the same neck of the woods! (my father strung hop poles on stilts just before i came along) but I much prefer Scotland to Kent. Looking forward to the next one, regards Kev.

Jo Woolf

Thanks, Kevin!! That’s very interesting about the Kent connections! I agree – we love Scotland too.

Ian Finlayson

A friend explored this area recently and linked me to your post. I really enjoyed reading your story about navigating the landscape, finding lost communities and piecing together the history. The struggles with vegetation and finding a safe path sound familiar and when combined with the hottest of days can be exhausting but rewarding.

Jo Woolf

Hi Ian, thank you very much – I’m glad you enjoyed the post! We loved exploring this area and finding Stronefield – such a quiet but atmospheric place. The beaches are amazing and even the clamber down the cliff was well worth it!

Sarah Cage

Marion Campbell wrote a children’s book – the Wide Blue Road – which describes the cave. We spent the whole summer holiday (I think in 1966 or 1967) trying to find it. I do now know where it is, though when I last went to look ( last summer) I couldn’t face the final scramble up the cliff to the concealed entrance, and I wasn’t sure whether it is still viable. We’ve tried to do What3Words to identify the position, but not sure we’ve managed it. I do have it on a Strava walk trace though, and I’m in the process of writing an illustrated booklet of a walk from Balimore via the Mill Bay, up the “goat path” (I believe there were feral goats in the 1960s), past Lochan Sithean Buidhe (which we were told meant the yellow fairy lochan), and then back down past Stronefield.

Jo Woolf

Hi Sarah, that’s very interesting to know, thank you for sharing this! The whole summer holiday – it must be well concealed – I don’t feel quite so bad now that we didn’t find it on one afternoon! Is it possible for you to send me a screenshot (or something!) of your Strava walk trace with the rough location? Was it quite large inside? With best wishes, Jo

Sarah Cage

I’ve been to Kilmory every summer for at least 70 years (my grandparents built Dun a Bhuilg, and my other grandfather was the junior architect. My mother bought the Schoolhouse in Kilmory in 1961, and we’ve been the maintenance crew for the last 15-20 years). I’ve wandered all ofer the area, and found the hut circles above the Abhainn Mhor gorge, and a half-cut-out mill stone right up in the hills (but downhill all the way to the mill), the cup and ring marked rock under Cnoc Stighseir, and some more shielings up about Ellary (found originally from Abhainn Mhor side, not sure I could find them again)

From my memory, the “cave” isn’t that big – about 10 feet by 15 – a place where one bit of cliff has dropped, leaving a 5-6 foot high slice. I’ve now finished the illustrated book (for my grandchildren) including the Strava trace.

If you send me an email address, I could send you the pdf (expecting to sell the books for £2-3 – this is the sixth book I’ve written for our grandchildren of walks in the Kilmory area – I want to record the information which my father (Owen Lewis) passed on to me).

Jo Woolf

Hi Sarah, thank you very much for your update and information about your new book – congratulations, and a lovely idea to preserve these details for your grandchildren. I’d be delighted to receive a copy. My email is jo(at)thehazeltree.co.uk