Glengarrisdale and Maclaine’s skull – a mystery re-exhumed

If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you might remember that last year we visited Glengarrisdale on the north-west coast of Jura. It was here, in 1647, that the Maclaines of Loch Buie, who had a fortress on the hill above the bothy, had a set-to with the Campbells of Craignish. Plenty of blood was spilled, and for some reason a skull of one of the murdered Maclaines lingered above ground, either in a cave or on a rock on the shore, for over 320 years. From what I can gather, it was last seen in 1972.

You can read the full story here: Glengarrisdale and Maclaine’s Skull

Quite how Maclaine’s skull managed to survive at Glengarrisdale for so long is a mystery in itself. Its resting place was known to local people and it was exhibited to visitors on several occasions. In the late 1800s, the geologist Sir Archibald Geikie examined it and noticed that it bore the cuts of a claymore.

Maclaine’s skull was such an long-established feature that it was marked on old OS maps. There was a superstition that, if it disappeared, it would always return, but by 1976 it had disappeared and it has yet to fulfil its destiny and come back. However, I’m not even sure how many people know where to look for it. For all we know, it could be languishing in one of the many inaccessible caves that pierce this rocky coastline. One of them – but which one? – is still marked on OS maps as ‘Maclean’s Skull Cave’ (their spelling).

And that really brings me to why I’m writing this post, because last week we got the chance to go back to Glengarrisdale and have another look. Colin and I joined a boat-charter group of seven, all keen for an adventure. On a morning that promised clear skies and hot sun we piled into Farsain, operated by Tony and Julie, plastered ourselves with sunscreen (a rarely-needed commodity on the west coast) and set off exuberantly through the Corryvreckan, whose waters were gently swirling on the slack tide. It was good to see so many birds – gannets, guillemots and eiders – and a pod of porpoises broke the surface occasionally, quite far off, no doubt hunting for fish.

The Corryvreckan

Approaching Glengarrisdale

Scrambling out onto the rocks at Glengarrisdale, I remembered its wild magic and felt a rush of pleasure to be back. The curve of the sand, stained with seaweed and warmed by the sun; the sloping expanse of green foreshore – reedy in spring but now a waving sea of bracken; the red-roofed bothy, looking neat and freshly whitewashed, and the peaty river gurgling its way out to sea. We deposited our bags on its bank and I rinsed my arms in the cool water.

We’d come to Glengarrisdale on a kind of mission, which was to search for clues to the whereabouts of Maclaine’s skull. Was it really lost, or was it hidden away somewhere? Our friend Jarek, who was one of the party, believed that the Skull Cave was somewhere between the bothy and the shore, so we all headed over there for a closer look.

Bracken isn’t my most favourite thing. Apart from harbouring ticks – which I try not to think about – it masks the rocks, the holes and the bogs that lie beneath, so you have to be extra careful about where you put your feet. But you can’t go to Jura and then moan about the bracken, so I just plunged into it and looked forward to coming out the other side.

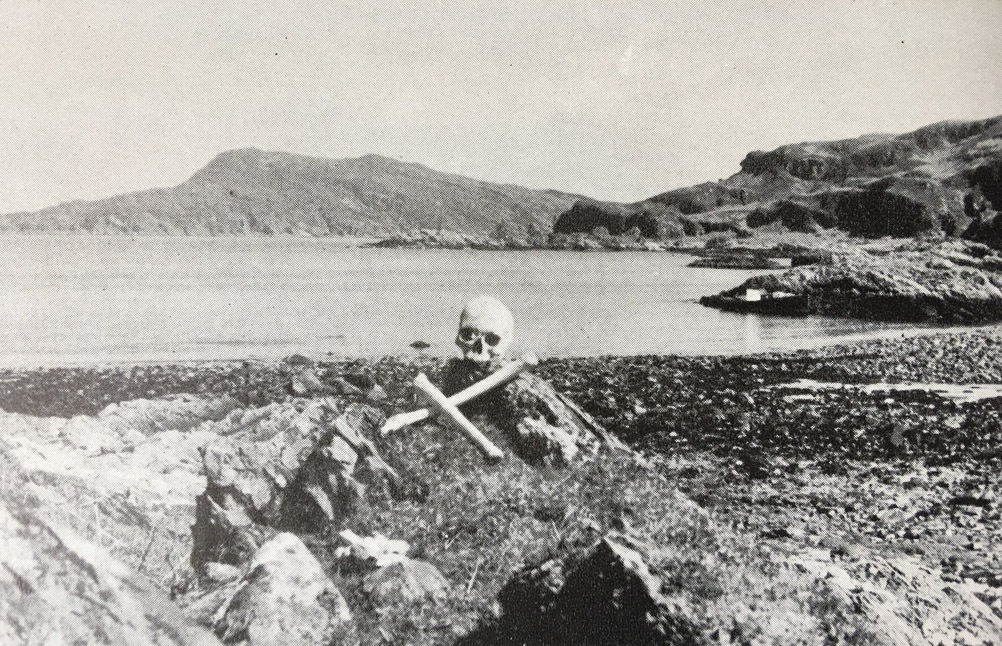

In an old black-and-white photo (above), reproduced in John Mercer’s Hebridean Islands (1974), the skull has been posed on a rock, and I was keen to pinpoint the exact location. You’d think it would be easy, but it wasn’t. A bewildering number of rocky knolls were poking out of the bracken, and each time I convinced myself that this could be the one, but the background didn’t quite match up. Colin was excited to find some field gentians in flower, and many of the boulders wore a pink topping of heather.

Field gentian

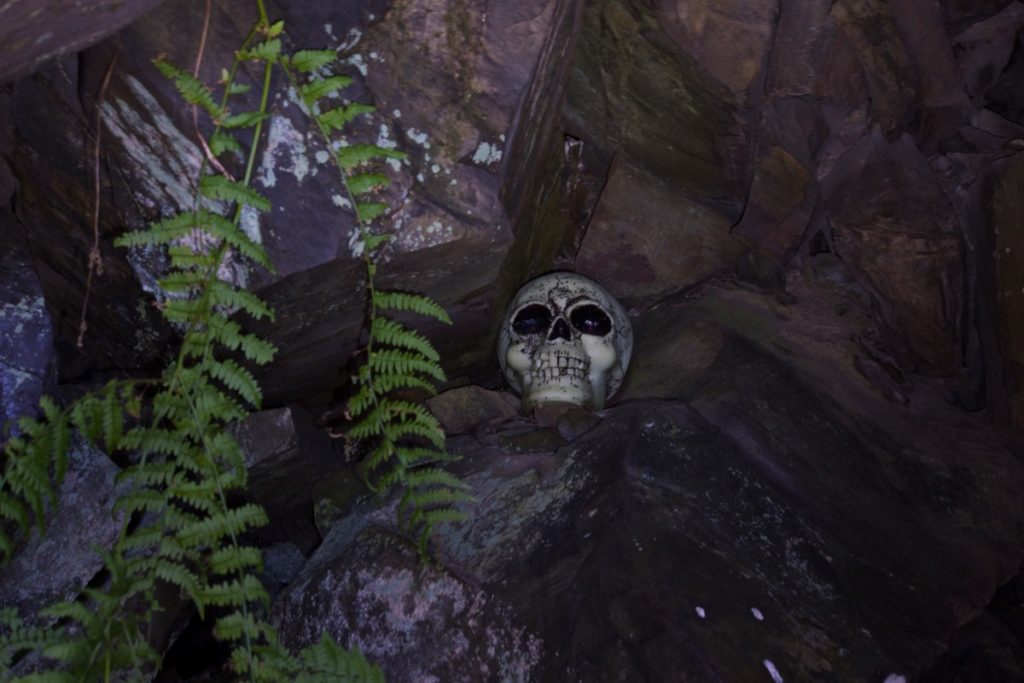

We’d all temporarily lost sight of one another when Jarek shouted, from about half-way up a cliff, “I’ve found a skull!”

It’s amazing how quickly you can move across difficult terrain when you really want to. We found Jarek standing on a ledge next to a small cavity, its entrance fringed with bracken and nettles. He looked like he’d had quite a surprise. “I think it might be plastic,” he said, half-apologetically. We bent and peered into the darkness. A rather ghoulish human skull gazed back at us. In its black eye sockets, something glittered. It was obviously fake – a Hallowe’en toy – but for a brief second it tricked my mind, even though I knew it wasn’t real. I wish I’d seen Jarek’s face when he first spotted it.

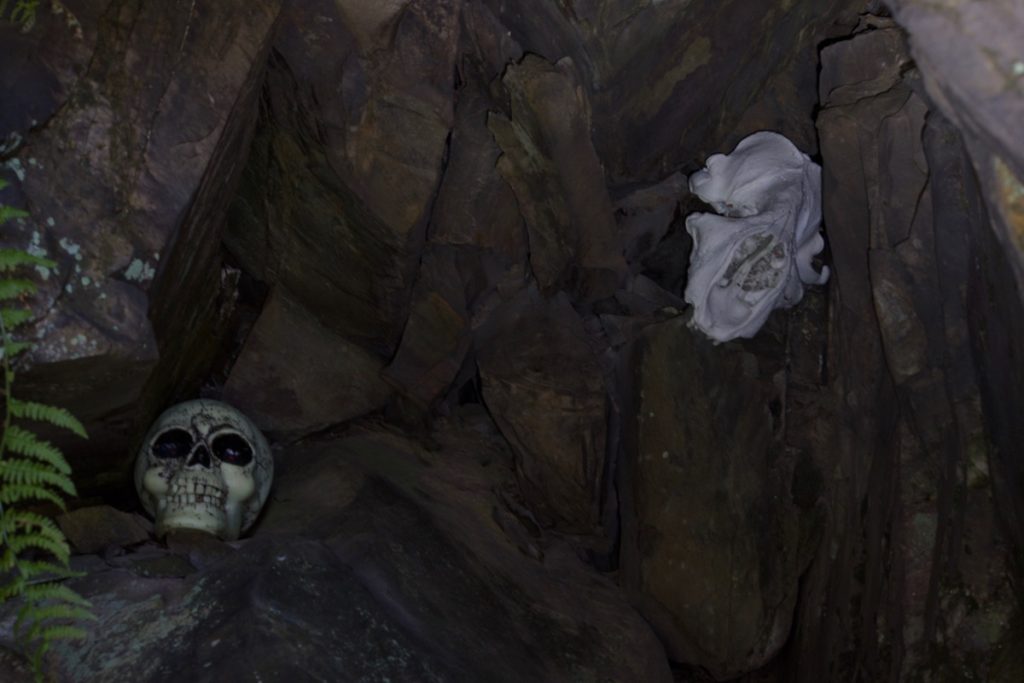

Just for good measure, a seal’s skull had been positioned close by.

Just for good measure, a seal’s skull had been positioned close by.

None of us could quite believe what we were seeing. It certainly proves that if you look for something hard enough, you’ll find it! Tony was the brave explorer who finally brought the skull out, and he posed with it like Hamlet in the famous graveyard scene. The sunlight must have done it good because when he put it back in the cave, it glowed in the dark.

“Alas, poor Yorick!… or is that Jarek?”

“Alas, poor Yorick!… or is that Jarek?”

Well, if that was someone’s idea of a trick, it caught us out perfectly! Has it been found before, I wonder? But we still have questions: was this the real Skull Cave? Did some prankster take the genuine one away with them and replace it with a fake? (If so, please bring it back!) Or did they just find a convenient hollow and plant a plastic skull there in memory of Maclaine? We’ll never know, but it gave us a good laugh.

A few hours later Farsain was whisking us homewards over a silky sea. We were content, windblown, tired, a bit sunburnt, but Jura had cast its spell over us all. I don’t know how many people go looking for a 300-year-old skull on an island, and actually find one. There can’t be many.

Thank you to everyone who made this such a special day: Julie and Tony of Farsain Cruises, and Jarek, David, Neil and the girls.

More about Glengarrisdale:

- Canmore: Maclean’s Skull Cave

- Canmore: An Aros

- National Library of Scotland

- Lord Archibald Campbell, ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition‘ (I, Argyllshire) (1889)

- Sir Archibald Geikie, ‘Scottish Reminiscences‘ (1904)

- Scotland’s Places – Argyll OS name books, 1868-1878

- Peter Edwards, ‘Peace, Love and Glengarrisdale Bothy‘, Writes of Way, October 2010

- John Mercer and Susan Searight, ‘Glengarrisdale: confirmation of Jura’s third microlithic phase’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 116, 1986

- John Mercer, ‘Hebridean Islands‘, 1974

Photos copyright © Colin Woolf

2 Comments

Karen

Sounds like you guys had a splendid adventure and so did I reading about it. Thanks so much for sharing it.

Jo Woolf

We certainly did! It was one of those special days to remember. Thank you, Karen.