Sueno’s Stone

On 13th or 14th April 1746, an English soldier named James Ray was riding towards Inverness with a company of Government troops under the command of the Duke of Cumberland. Ray had an interest in history, and on reaching the town of Forres he stopped to examine an eye-catching wayside feature. He wrote:

‘Just before we enter’d this Town on the Right Hand, we were presented with an Obelisk, a flat square Pillar of Stone, which rises about 23 Foot above ground, and is said to be no less than 12 or 14 Foot below, and its Breadth near five; it is all one entire Stone; great Variety of Figures are carved thereon, some of which are distinct and visible, but the Injury of the Weather has obscured those towards the Upper Part; what the Import or Signification of it is, I could not be informed: Camden* says, it was erected as a Monument of the Fight between King Malcolm, Son of Keneth, and Sueno the Dane.’

*William Camden’s Britannia, first published in 1586

Ray and his company moved west, passing through Nairn on their way to Culloden Moor, where, a couple of days later, a battle would shatter the hopes of an exiled prince and change the nature of Highlands forever.

The relic that caught his attention, and which he described in his account of the Jacobite rebellion, is known as Sueno’s Stone. I’ve often seen pictures of it, so I expected it to be quite a size, but still I was totally unprepared for the shock, when we went up to Forres the other day and saw it at first hand. It is absolutely huge.

Sueno’s Stone stands over 21 feet (6.5 m) tall, and is nearly four feet (1.2 m) broad at the base. It is set into a massive socket stone, which is partly buried. Stabilising stone steps were added in the early 18th century.

You’d think that the stone’s visual impact would be undermined by its current situation, on the outskirts of a housing development with the hum of traffic from the busy A96 less than a hundred yards away. On the contrary: it looks like a giant from another, more dangerous time, that has had to be restrained inside a glass case for the safety of passers by. Its presence is extraordinary. You can feel the power of it, even though you can’t touch it (and I did wish that I could).

So, at the time that this stone was first put up, which was sometime between the late 9th and early 10th centuries, we can only imagine with what awe it must have been regarded – and, according to all the theories about its origin, that was exactly what its designers intended. On the side that faces roughly east, which is the side you see first, dozens of small human figures are carved in a series of panels. This stone is telling its own story, like a graphic novel – and the story is one of conflict and violence.

Although they are much weathered, it is possible to make out that the figures are armed; some are on horseback, while some are on foot. According to a description published in Canmore’s site report (an extract from Exploring Scotland’s Heritage, 1986), the panels show, in succession from top to bottom, the arrival of an army in preparation for a battle; men fighting on foot, including a match between champions of both sides; a besieged stronghold (which may be a broch); the decapitation of prisoners, whose bodies can be seen laid out in a row; horse riders (or just horses) fleeing from rows of soldiers; a curving shape, perhaps a canopy, over more bodies and heads including one in a kind of square ‘frame’, which may denote a significant person; and the dispersal of the vanquished army, which even now has a look of savage triumph about it. The report observes that ‘this is war reporting on a monumentally self confident scale.’

Sueno’s Stone must therefore commemorate a battle of huge significance. The victors may have wanted to leave a permanent mark on the landscape, reminding those opponents who were left (if there were any) just how powerful they were. But who were the combatants, and when did it happen? Did the battle take place here, where the stone stands? Do we have any clues at all?

Firstly, it seems to be accepted that the stone stands on or near its original position, although it may well have lain buried in the ground for many centuries. As for the battle it depicts, there are several theories. The first involves the stone’s traditional name of Sueno: it was claimed by some early historians that Sueno or Swein was a Norse leader who clashed with the Picts or the Scots (or both). Adding colour to this theory is the presence of a large Pictish fort a few miles away at Burghead which was destroyed by fire in the 10th century, quite possibly by Viking raids. In 1726, historian Alexander Gordon noted that the connection between a ‘King Sueno’ and this stone was long known.

The 19th century historian, W F Skene, saw in the carvings a possible depiction of Sigurd the Mighty, Norse Jarl or Earl of Orkney. The Orkneyinga Saga tells how Sigurd defeated a Pictish leader known as Máel Brigte the Buck-toothed, then cut off his head and strapped it to his saddle; but Máel Brigte had his revenge even after death, because his protruding tooth cut into Sigurd’s leg and he died of the resulting infection.

Curving shape, perhaps a canopy or a bridge; immediately beneath it on the left is a row of bodies lying horizontally; on the right are severed heads, one of which is surrounded by a square ‘box’

A third scenario draws in a figure called Dubh (Duff). He was King of Alba, a kingdom of both Picts and Scots, and was killed by the men of Moray (which had its own power-base) in a battle that took place at Forres in 966. The information sign at the stone explains that Dubh’s body is said to have lain under a bridge at Kinloss, and suggests that the curious curved shape – suggested earlier to have been a canopy – could be the bridge in question. Furthermore, the carved head with the square ‘box’ around it could be the head of the king.

There is another theory, which argues that the defeated men are Picts who were defeated by the Scots under Kenneth mac Alpin (or one of his dynasty) in the mid-9th century. In a paper published by the Scottish Society for Northern Studies (Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters, 2019), historian David Sellar goes further and suggests that a scene on the reverse of the stone may depict the inauguration ceremony of a new king.

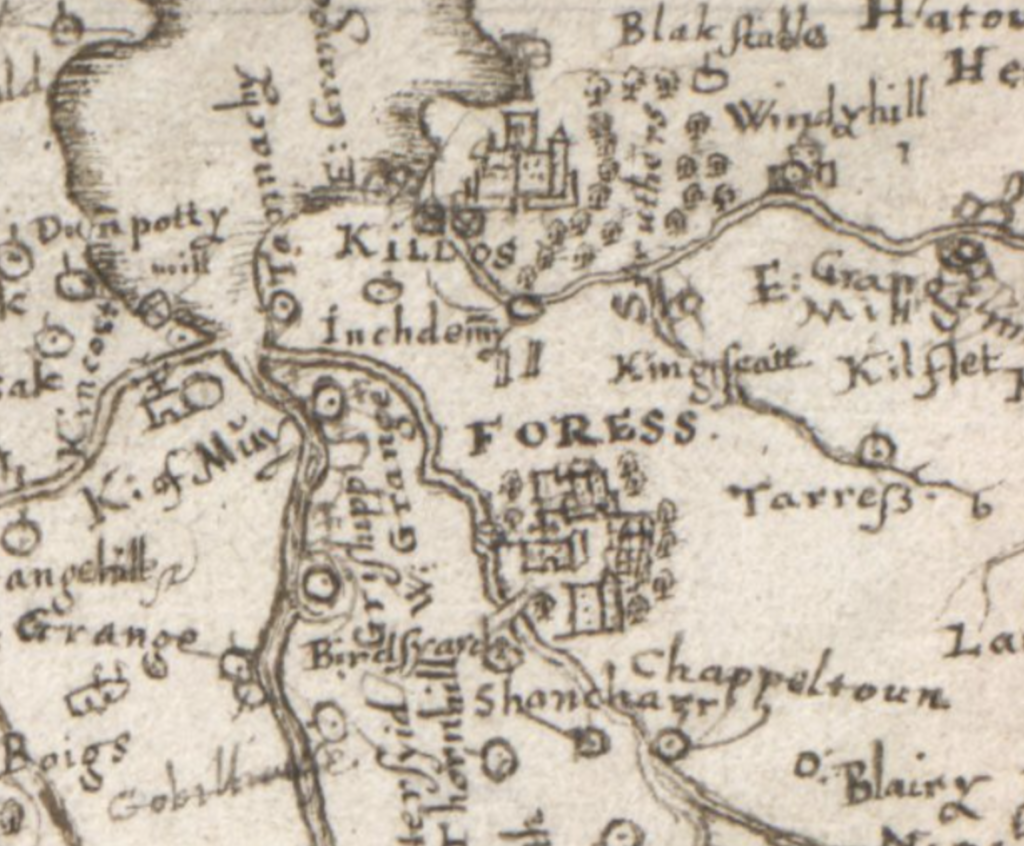

Then it gets even more intriguing, because on Timothy Pont’s Mapp of Murray (Map of Moray, c.1590), two stones of similar size and height are depicted, north of Forres. Did Sueno’s stone once have a twin? On John Ainslie’s map of Scotland (1789), two ‘curious carved pillars’ are drawn and labelled. Written sources make no mention of two stones, and Historic Environment Scotland’s Statement of Significance says that ‘the issue of a putative second stone is… complex and still open to debate.’

Timothy Pont’s map, c.1590, showing two standing stones just above the ‘O’ of ‘FORESS’ (map courtesy NLS)

John Ainslie’s map, 1789, which illustrates and labels two ‘Curious Carved Pillars’. The remains of a fort are shown on Burgh Head (map courtesy NLS)

I have barely mentioned the west-facing side, most of which is taken up with an enormous wheel-headed cross surrounded by a profusion of interlace designs. This in itself is staggeringly beautiful. The conversion of the Picts to Christianity is thought to have begun around the 6th century, with the arrival of evangelising missionary-saints such Ninian and Columba. Historic Environment Scotland says: ‘The carved cross… suggests that this site was a place where people came to pray, perhaps in gratitude for victory in the battle it records, or to remember a patron now long forgotten.’

There has been a suggestion that the cross may originally have faced east, not west, and that sometime in the stone’s more recent history it was re-erected with a different orientation. This may have happened more than once, especially because the cultivation of crops in the surrounding field would have loosened the topsoil. It is known that in 1700, Lady Ann Campbell, Countess of Moray, ordered some stone steps to be built around the base of the stone, to stop it toppling over.

I wondered whether any archaeological excavations ever yielded evidence of a battle, but it appears not. Historic Environment Scotland says that, in 1812 or 1813, eight skeletons with clothing and jewellery were recorded as being found in the vicinity of the stone, and subsequent discoveries (still in the 1800s) included weapons, a Roman coin and stone coffins. However, the locations of these finds are not known.

The slim sides are covered with elaborate scroll-work, in which human figures appear (I found these impossible to make out)

According to legend, Sueno’s Stone marks the place on the ‘blasted heath’ where Shakespeare’s Macbeth met the three malevolent witches who made such fateful predictions about his life. Macbeth’s companion, Banquo, asks:

How far is’t call’d to Forres? What are these

So wither’d and so wild in their attire,

That look not like the inhabitants o’ the earth,

And yet are on’t?

Act I, Sc.3

It is also said that the witches were captured and imprisoned within the stone, and that if it is ever broken they will escape and cause further mayhem. In 1787 Sueno’s Stone was visited by the poet Robert Burns, who had been staying with the Brodie family of nearby Brodie Castle. He wrote: ‘Mr Brodie tells me the muir [moor] where Shakespeare lays Macbeth’s witch meeting, is still haunted – that the country folks won’t pass by at night.’

This long-standing horror of witches was a country-wide superstition, fuelled in the 16th century by the royal witch-finder himself, King James VI. In Forres, many unfortunate women were apparently rolled down from nearby Cluny Hill in barrels and then burned to death. Not far from here, next to a low roadside wall in the centre of town, a boulder called ‘the Witches’ Stone’ is said to mark the spot of one such burning. And at a time of such relatively recent barbarity, Sueno’s Stone would have seemed just as ancient as it does to us now.

–

Reference and quotes:

- James Ray, A Compleat History of the Rebellion, from its First Rise in 1745, to its Total Suppression at the Glorious Battle of Culloden, in April 1746 (1747).

- David Sellar, ‘Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters’ (PDF), from Moray: Province and People (Scottish Society for Northern Studies, 1993

- R P J McCullaugh, ‘Excavations at Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1995

- J G Lockhart, The Life of Robert Burns, 1828

- Canmore site report

- Historic Environment Scotland’s Statement of Significance

- HES: arrival of Christianity in Scotland

- Maps courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

Images copyright © Colin & Jo Woolf

10 Comments

davidoakesimages

Well that is quite a read… all those times visiting and passing through Forres and totally unaware of the stone (pillar). Thanks so much again for yet another fascinating post 😃

Jo Woolf

Thank you, David! It actually took a bit of finding, because it’s down a no-through road on an estate, not at all where I imagined. Absolutely worth it though!

Finola

What an extraordinary monument! It reminds me of Irish high crosses, of course, and probably dates from a similar time, but I’m not sure there are any quite THAT big. Some have carved scenes of soldiers and some were likely carved as part of a display of wealth and power by high-status individuals. Here’s a good piece on one of them: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/ireland-s-high-crosses-medieval-art-and-engineering-1.4230543

Jo Woolf

I know, it’s jaw-droppingly huge! Thank you for the article, I enjoyed reading it. Those carvings have survived amazingly well, in comparison. Interesting to know that the work of one individual sculptor can be recognised and traced. Just erecting a cross in the right position must have been so risky!

freespiral2016

This is just an incredible stone, and what a history!

Jo Woolf

Yes, it’s fascinating! So many possibilities. Incredible to think of the people who have stood and looked at it, over about a thousand years.

Bob Hay

One could touch it in the 1950’s Jo. I was at the Outward Bound Sea School in Burghead (itself a massive Pictish fort http://www.burghead.com/burghead-fort/) for a month and we were taken on a trip to see the stone. With imagination running riot you could almost feel energy surging through your arm touching it and your scalp tingling.

Did you visit the well at Burghead and see the Pictish bull carvings?

http://www.burghead.com/the-well/

Jo Woolf

How amazing to be able to touch it! What an incredible energy it must have. No, we didn’t visit Burghead but now I want to, haha! The well sounds fascinating. Thanks for the links.

Bob Hay

Jo, I’m sure your readers would be glad to know that Pictish stone carving is alive and well.

Master craftsman Barry Grove has replicated the magnificent Hilton of Cadboll monolith and it’s back in its original setting.

Reminds me of The Monolith in Arthur C Clark’s great movie, ‘2021 A space odyssey’

Jo Woolf

Fabulous workmanship on this! I love it. I didn’t know that the cross-side of the Cadboll stone was chipped off in the 1600s so it could be made into a headstone!