Ossian, Fingal and the Falls of Lora

‘The murmur of thy streams, O Lora! brings back the memory of the past.’

Carthon, from The Poems of Ossian, trans. James Macpherson, 1773

Flowing beneath Connel bridge, a few miles north of Oban, is a tide race known as the Falls of Lora. With every incoming tide the sea rushes up into the loch, and then with the ebb tide it pours out again, each time passing over a submerged sill of rock and creating a stretch of rapids with standing waves and boiling eddies.

The Falls on the ebb tide, with kayakers getting ready to play in them

We see them often, and every now and then I’ve wondered how they got their name. ‘Lora’ crops up in other place-names close by: Beinn Lora is a hill to the north, rising to 1,010 feet with stunning views out towards the islands; and according to the Argyll OS Name Books of 1868-78, the expanse of low-lying farmland called the Moss of Achnacree, described as being ‘studded with ancient cairns, rude Druidical temples, obelisks &c,’ was once regarded as ‘the celebrated plains of Lora.’

The name ‘Lora’ is said to derive from the Gaelic labhra, meaning ‘noisy’, presumably describing the sound of the falls. They feature in one of my favourite books, R Angus Smith’s Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1885), in which a group of friends (possibly invented by Smith himself) discuss the legends attached to a number of ancient places in Argyll. They visit Connel and cross the Falls of Lora by ferry at slack tide (this is in the late 1800s, before the bridge was built). As they wander around the cairns and hill forts at Benderloch and Achnacree, one of the friends, whom Smith calls Cameron, shares an old story which places the fortress of a legendary Irish warrior-hero, Fionn Mac Cumhaill, close to the Falls of Lora.

The name ‘Lora’ is said to derive from the Gaelic labhra, meaning ‘noisy’, presumably describing the sound of the falls. They feature in one of my favourite books, R Angus Smith’s Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1885), in which a group of friends (possibly invented by Smith himself) discuss the legends attached to a number of ancient places in Argyll. They visit Connel and cross the Falls of Lora by ferry at slack tide (this is in the late 1800s, before the bridge was built). As they wander around the cairns and hill forts at Benderloch and Achnacree, one of the friends, whom Smith calls Cameron, shares an old story which places the fortress of a legendary Irish warrior-hero, Fionn Mac Cumhaill, close to the Falls of Lora.

There’s a catch, though. Cameron is drawing on the Poems of Ossian, published by James Macpherson in the 1760s, which are set in a long-lost time of heroes and bards. For his sources, Macpherson claimed to have discovered ancient manuscripts which he translated from Gaelic, but historians now tend to think that he dreamed at least some of the stories up. He did, however, use the protagonists of pre-existing Irish legends as his inspiration.

As a narrator, Macpherson chooses Ossian, a talented bard who was the son of Fionn mac Cumhaill. In Ossian’s poems, Fionn is called Fingal, and he is the leader of a band of noble warriors known as the Fianna. He presides over a magnificent hill fort called Selma, right on the coast, where he hosts great feasts and his bards sing songs in praise of the warriors’ valour. In Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach, Cameron is convinced that Selma is the same place as Beregonium, a hill fort at Benderloch which (in another legend) was said to be the home of Deirdre and Naoise, whose story I told in this blog post.

Adding strength to Cameron’s argument is the fact that a watercourse called Lora is located close to the fort of Selma. Tragic or momentous events are played out against the backdrop of its sound: we hear about ‘the murmur of Lora’, ‘the echoing stream of Lora’, and ‘the banks of the roaring Lora’. It’s true that the Falls of Lora can fluctuate between a murmur and a roar, a phenomenon that gives them a life and a character of their own.

Site of the hill fort of Beregonium, seen from Beinn Lora

The story of Clessámmor and Carthon

One of Ossian’s poems tells of a warrior called Clessámmor, who attends a feast at Selma after an absence of many years. Fingal sees that he is haunted by a deep sadness, and says to him: ‘Mournful are thy thoughts, alone, on the banks of the roaring Lora. Let us hear the sorrow of thy youth and the darkness of thy days.’

A story of heartbreak and loss is shared by Clessámmor, whose hair is now tinged with grey. As a young man, he was welcomed into a fortress called Balclutha which stood on the bank of the Clyde. Balclutha was the seat of a king called Reuthámir, and he had a daughter called Moina, whose hair was ‘as dark as the raven’s wing.’ Moina and Clessámmor fell in love, and were allowed to marry. But a jealous rival showed up and fought with Clessámmor, who killed him and was then forced to flee.

Clessámmor never saw Moina again, but knows that she died soon afterwards. He tells Fingal: ‘She fell in Balclutha, for I have seen her ghost. I knew her as she came through the dusky night, along the murmur of Lora: she was like the new moon, seen through the gathered mist; when the sky pours down its flaky snow, and the world is silent and dark.’

Fingal has reason to know that Reuthámir’s great fortress has since been ravaged by war, and stands desolate and empty. He commands his bards to sing the praise of Moina and welcome her spirit to their own hills, so that she will be among friends. But next morning a strange young war-chief appears from across the sea, bringing with him thousands of armed men: ‘Like the mist of ocean they came and poured their youth upon the coast.’

Fingal has reason to know that Reuthámir’s great fortress has since been ravaged by war, and stands desolate and empty. He commands his bards to sing the praise of Moina and welcome her spirit to their own hills, so that she will be among friends. But next morning a strange young war-chief appears from across the sea, bringing with him thousands of armed men: ‘Like the mist of ocean they came and poured their youth upon the coast.’

This can only mean trouble. Fingal and his warriors seize their weapons and go out to meet the newcomers. But first, Fingal wants to give their leader, who is called Carthon, a chance of peace, and he sends a bard named Ullin to negotiate. Ullin says: ‘Come to the feast of Fingal, Carthon, from the rolling sea! Partake of the feast of the king, or lift the spear of war! The ghosts of our foes are many… Behold that field, O Carthon! Many a green hill rises there, with mossy stones and rustling grass; these are the tombs of Fingal’s foes, the Sons of the rolling sea!’

Carthon replies with contempt. ‘Is my face pale for fear?’ he asks. ‘Why then dost thou think to darken my soul with the tales of those who fell?’ He has no wish for peace: he is looking for vengeance. His ancestral hall was Balclutha, and when he was an infant it was attacked by Fingal’s father, Comhal, and burnt to the ground. To Fingal, he says: ‘Have I not seen the fallen Balclutha? And shall I feast with Comhal’s son? Comhal, who threw his fire in the midst of my father’s hall?’ Fingal sees there is nothing for it but to fight.

But Carthon is only young, and Fingal, who is older and war-seasoned, is struck by doubt. He asks himself: ’Shall I stop him in the midst of his course before his fame shall arise? But the bard hereafter may say, when he sees the tomb of Carthon, Fingal took his thousands to battle, before the noble Carthon fell.’

Cautious, then, of his own reputation, Fingal selects some of his most trusted warriors to face Carthon in single combat. Cathul goes first, but is quickly slain. A warrior called Connal takes over, but Carthon breaks his spear and Connal lies ‘bound upon the field.’ (This refers to the tradition of binding a fallen foe with thongs).

Cautious, then, of his own reputation, Fingal selects some of his most trusted warriors to face Carthon in single combat. Cathul goes first, but is quickly slain. A warrior called Connal takes over, but Carthon breaks his spear and Connal lies ‘bound upon the field.’ (This refers to the tradition of binding a fallen foe with thongs).

Then it’s Clessámmor’s turn. As the noble warrior advances, Carthon sees that he is older in years than himself, and has a sudden premonition. Should he kill this man, or preserve his life? ‘Stately are his steps of age! Lovely the remnant of his years! Perhaps it is the husband of Moina… often have I heard that he dwelt at the echoing stream of Lora.’

Carthon parries Clessámmor’s spear, and asks him: ‘Warrior of the aged locks! Is there no youth to lift the spear? Hast thou no son to raise the shield before his father to meet the arm of youth? Is the spouse of thy love no more? Or weeps she over the tombs of thy sons?’

Clessámmor has no idea that he is facing his own son. He demands to know what Carthon is talking about. He is renowned in battle, he says, and the mark of his sword is in many a field. Defiantly, he tells him: ’Age does not tremble on my hand. I still can lift the sword. Shall I fly in Fingal’s sight, in the sight of him I love? Son of the sea! I never fled.’

Still unsure, Carthon breaks Clessámmor’s spear and seizes his sword instead of killing him. But as Carthon is binding him, Clessámmor reaches for his dagger and stabs him. Mortally wounded, Carthon turns to Fingal, who accepts his sword and assures him of a hero’s burial in this land that is far from his home. Carthon says: ‘A foreign tomb receives, in youth, the last of Reuthámir’s race… But raise my remembrance on the banks of Lora, where my fathers dwelt. Perhaps the husband of Moina will mourn over his fallen Carthon.’ With horror, Clessámmor realises what he has done.

For three days Fingal and his warriors mourn the death of Carthon, and on the fourth day Clessámmor dies of grief. They are buried with honour below Fingal’s fort, and he commands his bards to sing their praises on the day that autumn returns: ‘Who comes so dark from ocean’s roar, like autumn’s shadowy cloud? Death is trembling in his hand! His eyes are flames of fire! Who roars along dark Lora’s heath? Who but Carthon, king of swords!’

(This is greatly abbreviated and paraphrased from Carthon, A Poem, from James Macpherson’s Poems of Ossian, 1773)

–

In Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach, Cameron and his friends walk over the Moss of Achnacree, ‘the celebrated plains of Lora’, where a concentration of burial cairns suggests that this was once a place of significance. Like Ossian, Cameron sees ’the tombs of Fingal’s foes, the Sons of the rolling sea.’ One of the cairns, which Smith excavated in 1871, is traditionally called ‘Ossian’s Cairn’, suggesting that the bard himself was buried there. In view of the proximity of Selma – or is it Beregonium? – it’s tempting to imagine that Carthon and his father, Clessámmor, rest beneath the others.

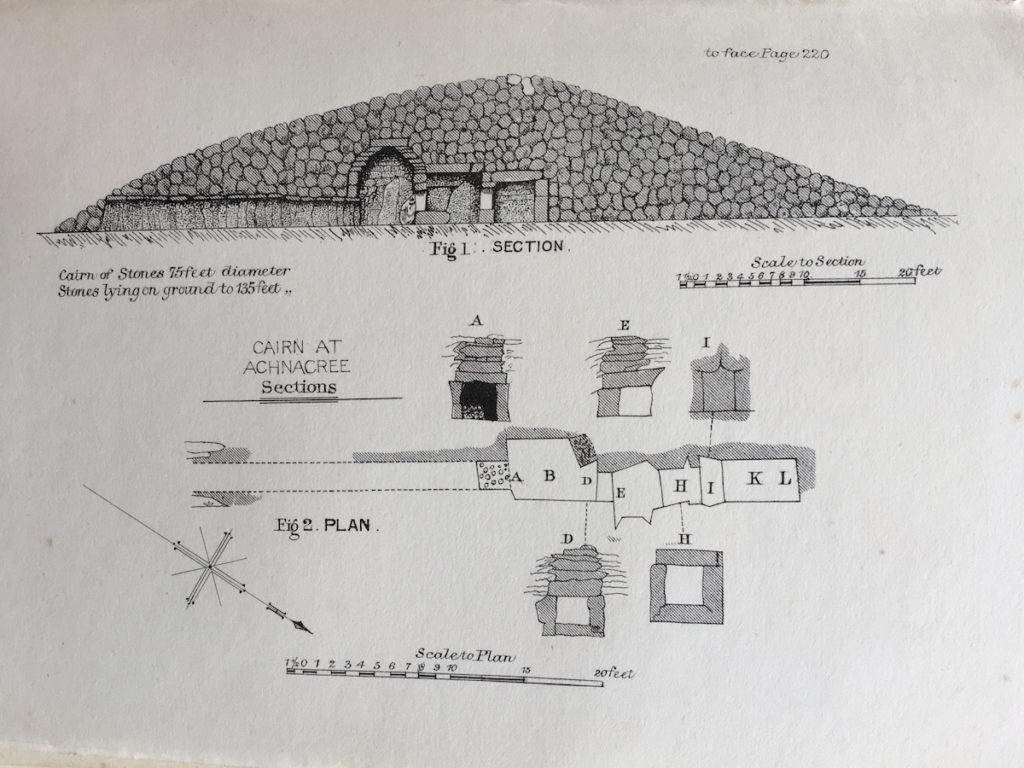

Carn Ban (White Cairn or Ossian’s Cairn) at Achnacree, excavated by Smith in 1871. He found a passage leading to three inner chambers, each roofed by a capstone. The most significant finds included a bowl (now identified as Neolithic) and fragments of two others. Smith’s work attracted a lot of local interest. He wrote: ‘One woman who lived here… said she used to see lights upon it in the dark nights.’

Drawings of Ossian’s Cairn, from R Angus Smith’s Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach. Unfortunately, the structural details illustrated here were lost in the process of excavation.

Cameron points to a ridge called Tom Ossian or Ossian’s mound, and says that local people ‘will tell you that Ossian used to sit there and admire the scene whilst his father Fingal reigned in Selma on the Dun we have studied.’ One of Cameron’s companions, a man called Loudoun, replies: ‘They may fancy anything, but the smallest trace of authority is wanting.’

Loudoun is absolutely right, but he is missing the point about legends. There’s no substance to them. We might as well try and catch the wind. We can’t locate the graves of Ossian and Carthon and Clessámmor, and we’ll never dig up their weapons. They live in a different realm from our own. Meanwhile, the Falls of Lora continue to flow, backwards and forwards, sometimes reaching a roar that Ossian himself would no doubt have liked to hear. In a way, the sound is like a story that is constantly being told and re-told. Its words are uttered with the outgoing tide but then they flow back on themselves, replenishing the source from which they came.

Looking across the Falls towards the Moss of Achnacree or ‘the celebrated plains of Lora’

Old Irish legends are preserved in many other place-names in Argyll: examples include the Tomb of the Giants by Loch Nell, Diarmuid’s Pillar in Glen Lonan, and two duns, each claiming to be the Fort of the Black Dogs: Dun a’ Choin Duibh in Knapdale, and Caisteal nan Coin Duibh here in Craignish. With his Poems of Ossian, James Macpherson has added another layer to those wonderful tales.

Reference:

- The Poems of Ossian, trans. by James Macpherson (1760-63)

- R Angus Smith, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1885)

- The Argyll OS Name Books, 1868-1878, Vol. 1

- Canmore: Carn Ban or White Cairn, also known as Ossian’s Cairn

- The Falls of Lora – information website

Photos copyright Colin & Jo Woolf

8 Comments

Bob Hay

Beregonium does sound a bit ‘Roman’ Jo. Apparently it was a misprint

Appears there’s a valid reason to doubt if any Royal Pictish city was there at the Falls..

https://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/descriptions/84810

But that wouldn’t distract from a great story to people huddled round an Iron Age fort fire hearth on a cold wet windy winter’s night.

Jo Woolf

I know, Bob, the name has evolved so much that it’s impossible to tell what it was originally! I see that Groome was a contemporary of Smith and they must have been aware of each other’s work. At the bottom of this post are some links to more recent articles that discuss the origins of Beregonium/Dun Mac Uisneachan: https://thehazeltree.co.uk/2022/07/13/deirdre-and-the-sons-of-uisneach/

Finola

classic story, wonderfully told. Do you listen to podcasts, Jo? You might enjoy Into the Mythic – start with Brotherly Love.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Finola! Yes, I do occasionally listen to podcasts – have just found Into the Mythic so will give it a go!

Scott K Marshall

Great blog – I shot this area myself recently – my Daughter is named after the falls.

Jo Woolf

Thanks, Scott! Good to hear from you again. What a lovely name for your daughter!

W N Vossbrink

‘Tis a shame that few people today know of and appreciate Macpherson’s Ossianic poems. I’ve loved them for over thirty years.

Jo Woolf

Yes – maybe it’s because they were so heavily criticised at the time, and they’ve never been appreciated in later years for what they are.