The Prince’s Cave, Loch nan Uamh

A few years ago, while on a drive up to Mallaig, we stopped to look at a cairn by the side of Loch nan Uamh. This isn’t a prehistoric cairn, but a 20th century one – it’s a memorial, in fact. A plaque on it says (in English and Gaelic):

‘This cairn marks the traditional spot from which Prince Charles Edward Stuart embarked for France, 20th September 1746. Erected by the Forty-five Association, 1956.’

Having spent months on the run from the Duke of Cumberland’s forces after his defeat at the Battle of Culloden, Charles finally managed to board a ship that had slipped into the loch, and was spirited away to France. Several of his supporters went with him, taking the only option that offered survival.

Looking at the record of the cairn on Canmore, I noticed that a couple of miles further west, still on the loch shore, is a feature called Prince Charlie’s Cave. It would be good to find that, I thought, and then forgot about it. Yesterday, we decided to go and look for it.

Loch nan Uamh, the ‘loch of the caves’, is a sea loch, dotted with wooded islands, that opens out into the Sound of Arisaig. The water laps round a hundred little inlets and steep rocky headlands, most of them covered with trees with no visible track to them. It strikes you that this would be a great place to hide if you knew the landscape. In those turbulent months, both before Culloden and after, this is what Charles’s supporters were thinking, too.

In 1745, Charles’s arrival in Scotland was just as surreptitious. On 22nd July the Duteillay, a French frigate, made landfall on the island of Barra Head (Berneray) in the Western Isles; here a man went ashore in search of a guide who could help navigate around the small islands, and he brought back Callum MacNeil, piper to the MacNeil chief. The following day the Prince was carried ashore onto a beach on the island of Eriskay.

In 1745, Charles’s arrival in Scotland was just as surreptitious. On 22nd July the Duteillay, a French frigate, made landfall on the island of Barra Head (Berneray) in the Western Isles; here a man went ashore in search of a guide who could help navigate around the small islands, and he brought back Callum MacNeil, piper to the MacNeil chief. The following day the Prince was carried ashore onto a beach on the island of Eriskay.

A few days later, the Duteillay arrived in Loch nan Uamh. The clans in this area were known to be staunchly Catholic, and Charles was confident of support. Having set foot on the Scottish mainland for the first time, he went to Borrodale House, home of Aeneas (Angus) MacDonald, and spent a couple of weeks rallying support. On 19th August 1745, at Glenfinnan on Loch Shiel, he raised his standard before an army of about 1,500 clansmen and declared his intention to fight for the throne he believed was rightly his.

When Charles returned to Borrodale in July 1746, things looked very different. His rebellion had been well and truly smashed. His followers (those who had survived Culloden) were being persecuted; their families were being turned out of their homes and their houses burned. This had happened to Aeneas MacDonald, who was now living in a bothy. But he offered Charles refuge all the same.

There were already rumours that French ships were somewhere off the coast, hoping to rescue the Prince. The entire countryside was being combed by government soldiers, and some of their information came from informers who had switched sides in an attempt to preserve the lives of their families. But if Charles could be concealed for a while, he might yet be saved.

According to contemporary reports, the Prince arrived in Mallaig by boat around 5th July, and his companions spent a few days finding out whether local clan chiefs would offer him protection. MacDonald of Morar was willing to do so, and went off to look for the young son of Clanranald. In the meantime, Charles and his party went to a cave and slept. Morar returned, saying he’d not found Clanranald, and could offer no further assistance. Under cover of darkness, the Prince’s party made their way towards the bothy occupied by Aeneas MacDonald of Borrodale.

John McKinnon, who had escorted Charles to Borrodale, roused MacDonald from his bed and first asked him cautiously if he had heard anything of the Prince. On hearing a negative, McKinnon asked, ‘What would you give for a sight of him?’ MacDonald replied, ‘Time was, that I would have given a hearty bottle to see him safe, but since I see you I expect to hear some news of him.’ McKinnon then revealed the Prince, and handed him into MacDonald’s safe keeping. MacDonald said: ‘I shall lodge him so secure that all the forces in Britain shall not find him out.’

Now, whether this cave on Loch Uamh was the cave in which Charles slept before he went to Borrodale, or whether it was the secure place where Aeneas MacDonald swore to hide him, the fact remains that it’s one of the many caves in which Charles is said to have taken refuge on his merry dance across Scotland. In The Flight of Bonnie Prince Charlie, Hugh Douglas and Michael J Stead write: ‘According to local tradition, Prince Charles spent two days in a cave close to the shore of the loch while Borrodale sent for his nephew Alexander MacDonald of Glenaladale to take over as guardian.’ (They add that Glenaladale had been wounded at Culloden, but came to the Prince without hesitation and became his chief support.)

Now, finding secret caves isn’t the most rewarding activity, unless you’re prepared to spend a long time looking in the most inaccessible places (they weren’t designed as visitor attractions, after all). We don’t have a great track record, having tried, and failed, to find a reputed Jacobite cave in the hills around Stronefield in Knapdale. But this one is marked on the map, after all. How hard could it be?

Quite hard, as it turned out. I’d read a brief description of how to get there, but it wasn’t detailed enough. Luckily it was low tide, which made crossing the bay a lot easier, but even on the other side the ground was extremely boggy. Streams were draining onto the shore, their courses hidden in mud with a grassy covering. The only option was to move quickly.

I’d read that the cave lies next to an oak tree, so I was glad when a big oak tree loomed up, next to a promising outcrop of rock. Nothing there. Another oak tree – nothing. We scrambled around, lost the path, found another (or was it the same one?) and carried on. In a wooded hollow, we looked across at an irregular rock face that might have been a coastal cliff at some stage. In the jumble of trees, rhododendrons and fallen boulders it was hard to make out any distinct features at all. But Colin found a way round the bottom, and was half-way up the side when he called out that he’d found it.

The opening was quite low, and we had to crouch to get in. From a fairly small outer chamber, we could see that there was, some three or four feet below, a potentially bigger one. Colin slid down with a torch, and I followed. The floor was mushy with dead leaves, and water was dripping from somewhere above. A kind of passage – obviously a natural one – opened out into a wide space with a high roof, large enough to contain several people comfortably. Whether or not Charles would have been able to cook a meal is difficult to say: maybe the smoke would have been seen. But he would have been near-impossible to find.

I have to admit that I’m not over-keen on caves, so I didn’t linger in there. The Prince didn’t stay long, either, but for different reasons. When Borrodale’s son went out to check the lie of the land, he saw ‘the whole coast surrounded by ships-of-war and tenders, as also the country by other military forces.’ The Duke of Cumberland’s soldiers had found out that Charles was in the area, and had thrown a cordon around the whole of Moidart to block his escape. A week or so later, the Prince managed to slip undetected between two guards, and headed, via Glenshiel, for Glenmoriston. Here, he slept in another cave, and declared himself to be ‘as comfortably lodged as if he had been in a royal palace.’

Charles was running around the hills in the summer, and biting insects were an absolute menace. John MacDonald of Borrodale wrote that the men ‘…greatly suffered by mitches [midges], a species of little creatures troublesome and numerous in the highlands; to preserve him [the Prince] from such troublesome guests, we wrapt him head and feet in his plaid, and covered him with long heather.’

Charles was running around the hills in the summer, and biting insects were an absolute menace. John MacDonald of Borrodale wrote that the men ‘…greatly suffered by mitches [midges], a species of little creatures troublesome and numerous in the highlands; to preserve him [the Prince] from such troublesome guests, we wrapt him head and feet in his plaid, and covered him with long heather.’

Charles played this desperate game of cat-and-mouse for another two months, relying on loyal Highlanders to conceal and guide him from one shelter to the next. Travelling east into Badenoch, he took refuge in Cluny’s Cage, a hide-out on Ben Alder where Ewen MacPherson of Cluny, Chief of Clan MacPherson, is reputed to have hidden for nine years after Culloden. In the early hours of 13th September, a couple of Cluny clansmen and a tenant of Lochiel arrived at the Cage with good news: two ships were in Loch nan Uamh, and were waiting to take Charles to France.

I’m not sure how much patience I would have had with the Bonnie Prince. Apparently, when he heard that he had a chance of escape, he played a trick on his host, John Roy Stewart, by hiding behind a door and jumping out at him so that he fell into a pool of water in a dead faint. Seriously, Charles?! These people were already under enough stress!

Back on the shore of Loch nan Uamh, Charles made a speech to the men he was leaving behind, assuring them that he expected to return and reimburse them for their losses and trouble. Then he was rowed out to the ships, along with about two dozen of his followers who had opted to go with him into exile. In the early hours of 20th September, the Hereux and the Prince de Conti weighed anchor and headed west, out past the Small Isles and into the Atlantic, charting a route that would keep them well away from British men-of-war.

Charles made it to France, but never returned to Scotland. Those men who had aided him were sought out and either executed or cruelly punished. In the Highlands, livelihoods and homes were destroyed, and an entire way of life was lost.

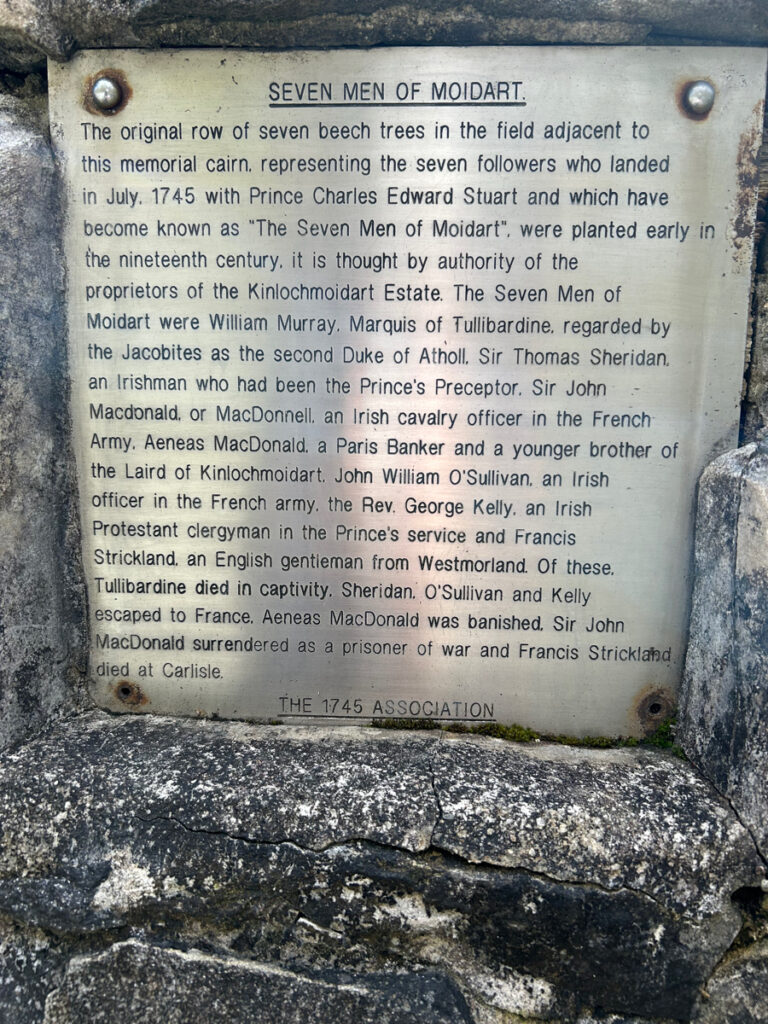

We decided to drive home via Inverailort, Acharacle and Strontian, crossing Loch Linnhe via the Corran Ferry. At Kinlochmoidart we passed another cairn, this one commemorating the ‘Seven Men of Moidart’, who accompanied Charles during his first landing on Scottish soil. They were so-called not because they came from Moidart, but because this was the region from which Charles launched his rebellion.

In the mid-1800s, a row of seven beech trees was planted in their honour. Unfortunately, they have been ravaged by age and storms, and only one or two survive.

Sources and further reading:

- Hugh Douglas and Michael J Stead, The Flight of Bonnie Prince Charlie (Sutton, 2000)

- Robert Forbes, Bishop of Ross and Caithness, and Walter Biggar Blaikie, The Lyon in Mourning (1895)

- Walter Biggar Blaikie, Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from his Landing in Scotland July 1745 to his Departure in September 1746, compiled from The Lyon in Mourning (1897) courtesy National Library of Scotland

- Canmore: The Prince’s Cairn

- The Jacobite Rebellions

- Scottish Cave and Mine Database

6 Comments

SIMON MCLAREN TOUGH

great stuff…..the Bonnie Prince always stirs the emotions

Jo Woolf

Certainly does! Thank you, Simon.

jocelyn markland

Prince Charlie’s Cave . Yes, that’s the correct cave as I learnt. I lived around the lovely Borrodale House for a while, and camped in the big field below. I’d lie awake at night and hear the last train, then the deer barking my presence, and watch bats swooping over the field.

Over a little fence and the cave is in the oak wood and tumbledown boulders.

It’s a very beautiful part of the world.

Jo (Jocelyn Markland)

Jo Woolf

Your description sounds wonderful, Jo! I can just imagine being there on a summer evening and listening to it all. A lovely place to grow up, I would imagine. Thank you for sharing it, and for confirming about the cave. We did wonder how many people visit now – the paths seem trodden up to a point, but not necessarily as far as the cave itself. With best wishes, Jo

STEVEN JOHNSTONE

Charles’s first landfall in Scotland was on Eriskay and not Barra.

Jo Woolf

Hello Steven, thank you for your comment. I’ve looked again at my sources, and in fact the first landfall (defined as sighting of land after a voyage) was at Barra Head, an island also known as Berneray. I had assumed that this was actually the island of Barra, so that was my mistake. This took place on 22nd July, and the next day the Prince was carried ashore onto Eriskay. I have edited my post to make the chronology clearer.