Orkney: the Ring of Brodgar

We arrived on Orkney late on a September evening, driving off the ferry into the streetlights of Stromness and then quickly leaving them behind as we made our way north towards Birsay. In the pitch darkness, knowing that we were passing close to the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness, I peered out of the window and tried to make out their shapes against the night sky. I don’t know if I was hoping that they glowed in the dark, but I could make out absolutely nothing.

So it was next morning, after watching a pale yellow sunrise over the sea, that we made our way south again in search of these iconic landmarks.

Approaching the Ring of Brodgar, with geese flying

Right away, we discovered that Orkney’s reputation for abundant birdlife is totally deserved. The fields held flocks of golden plovers, a sight I’ve rarely seen since my Shropshire childhood, all watching and listening intently for insects in the grass. Some were still in summer plumage, dark bellies fringed with gorgeous spangled ‘cloaks’, while others were already yielding to the onset of winter in more understated outfits of cream, brown and buff.

The morning was cold but calm, and when we got out at the Ring of Brodgar we could hear skylarks singing high above. No one else was about.

Because you have to walk uphill slightly to the stones, which are set in a wide, flat expanse of moorland, you don’t really get much of an impression of them until you’re right there, in their company. Then the whole place really strikes you with its size and stature, as if you’ve come upon it unawares.

The circle itself has a diameter of 338 feet (103 metres) and it stands within a rock-cut henge or ditch. As a result, the space within looks like an enormous stage, on which all the players are standing and facing inwards. And what impressive figures they are: slim and straight-sided, some with noticeably angled tops; up close, they are gnarled and weathered, furry with lichen, and curiously textured from the prolonged assault of wind, water and ice.

‘Divine feminine,’ I wrote in my diary, ‘a real temple feel.’ My inner druid obviously felt right at home. What struck me also was the elemental nature of this place: nowhere to hide, no shade, no shelter from any trees (there are precious few on Orkney). Just the wide-open sky, the equally wide-open moor, and water on almost all sides.

According to the Ness of Brodgar website, there is uncertainty about whether the stones and the encircling ditch were constructed at the same time. The stones themselves are thought to have been erected sometime between 2600 and 2400 BC. They were quarried from a number of different sites on Orkney, among them Vestrafiold, about eight miles away, where – amazingly – similar abandoned stones can still be seen, cut out and lying on the ground, apparently ready for transport. One theory, tried out by a recent TV documentary, suggests that seaweed was placed underneath them to speed them on their overland journey to Brodgar.

Today, only 27 upright stones survive from a circle that may perhaps have comprised 60 or more; the tallest survivor stands over 15 feet (4.7 metres) high. Access to the circle was by specially-constructed, diagonally opposing causeways to the south-east and north-west. Who walked across them into the ring of stones, and what did they do there?

A traditional story, the kind that is attached to stone circles elsewhere, tells how a group of giants were passing by one evening, and on hearing the toe-tapping music of a fiddler who was standing by the roadside they began to dance. They enjoyed themselves so much that they danced all night, but they lost track of time and at sunrise they were all turned to stone, presumably as a punishment for dancing when they should have been working (or asleep in their beds, or even in church).

Some archaeologists have suggested that the stone circle may never actually have been completed, but that it continued to evolve over a long period of time, during which people from different communities and successive generations might have made their own contributions. We can only speculate; but here, of all places, where rock is lying only just beneath the surface, I cannot imagine how hard it must have been to excavate this immense ditch, as well as the holes for the stones themselves, using only rudimentary tools.

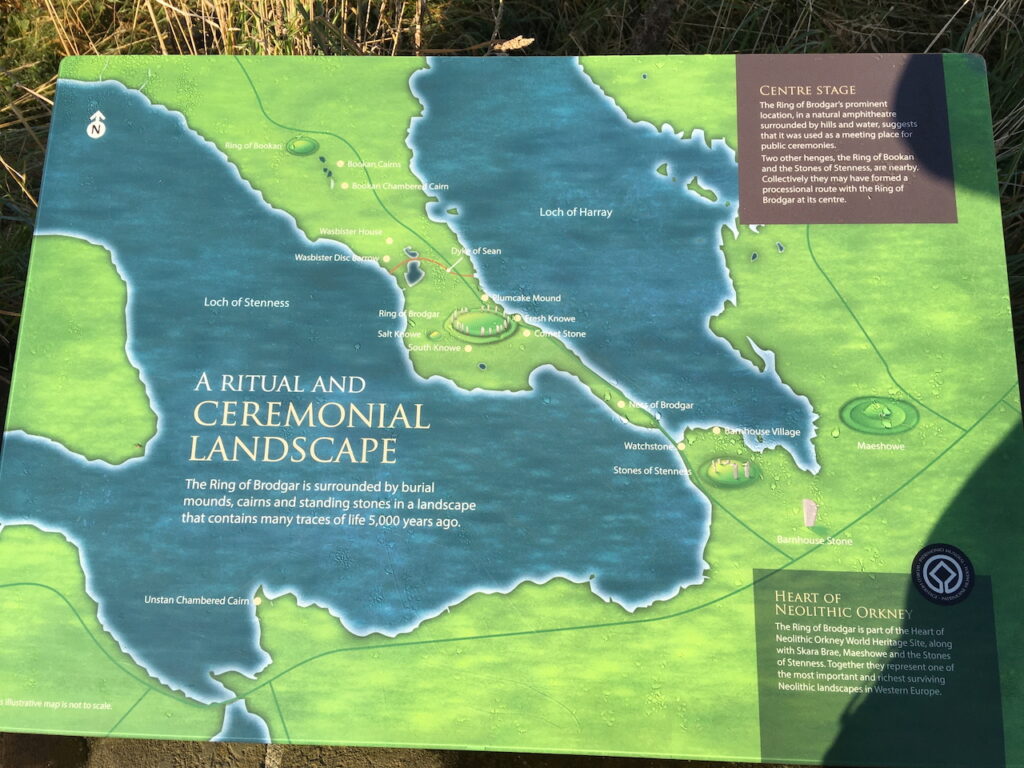

In the immediate vicinity are a number of burial mounds; according to Historic Environment Scotland, these likely date from between 2500 and 1500 BC.

Outlying stone (or a petrified fiddler, whichever you prefer!)

Looking across the Loch of Stenness to the hills of Hoy

It’s impossible to consider the Ring of Brodgar without looking also at the other prehistoric sites around the Ness of Brodgar: the Stones of Stenness, for example, and Maes Howe, a Neolithic chambered cairn. The Ring of Brodgar sits on a slim peninsula that separates the Loch of Stenness from the Loch of Harray; this spur of land is shaped roughly like a human fist, with a long ‘forefinger’ pointing directly at Stenness and its Watchstone, as if this is the answer to everything (perhaps it is!) That’s where we went directly after we’d visited the Ring of Brodgar – an interesting contrast, in several ways – and so that’s where I’ll go in my next blog post.

Meanwhile, I’d like to send you my very best wishes for Christmas and the New Year.

Map from information sign at the Ring of Brodgar

Further reading:

Photos copyright Colin and Jo Woolf

7 Comments

davidoakesimages

Great minds think alike…or so they say.. pop over to my post for today 😃

Jo Woolf

So they do! Solstice greetings to you, David!

bitaboutbritain

Wonderfully told and photographed. One abiding thought I have about stone circles is the organisation, management and effort that went into construction. Whatever their purpose, our ancestors were certainly determined to build them!

Jo Woolf

Thank you! Yes, I agree about that. I keep feeling there’s a big piece of our knowledge missing.

davidoakesimages

I am not sure that all the expert interpretation really explain the though , the imagination, the engineering and logistics behind the creation of the neolithic stone henges and circles. Apart from the shear skill and effort in construction, of stones that even today would be a challenge, I find it hard to understand how their knowledge and skills to source special stones from a great many miles away. Have we made progress I sometimes wonder. Solstice greetings to you and Collin… Iook forward to more Hazel Tree Posts in 2025

Jo Woolf

I totally agree, David. Not just cutting, transporting and raising the stones but also digging ditches out of rock with antler picks. It just doesn’t add up. Thanks for your good wishes and the very same to you!

davidoakesimages

Agreed…. it just seems so impossible..