The Kyle of Tongue: a battle, a hero’s grave and a cow with a gold coin

You might remember in a recent blog post that I mentioned a romantic-looking old fortress atop a promontory overlooking the Kyle of Tongue, which we noticed on our travels in search of wild flowers on Scotland’s north coast.

This turned out to be Caisteal Bharraich (anglicised to Castle Varrich). It’s not the biggest castle I’ve seen, but it seems to have a good deal of history attached to it. This quote is attributed to a minister of Tongue in 1792:

‘There is a cave in the rock upon which the castle [Varrich, near Tongue] is built called Leabuidh Evin Abaruich, i.e., John of Lochaber’s bed, whither he is said to have retired in time of danger. A family of Mackays is descended from him, and are reported still to have in their possession his banner, with the motto wrought in golden letters, Biodh treun—Biodh treun, i.e., Be valiant.’

Rev William Mackenzie, from the First Statistical Account of Scotland, 1792, quoted by Angus Mackay in The Book of Mackay (1906)

In his Book of Mackay (1906), Angus Mackay explores the lineage and history of Clan Mackay, whose ancestral lands lie in Strathnaver in the modern county of Sutherland. (Strathnaver is the ‘strath’ or floodplain of the River Naver, which rises from Loch Naver beneath the isolated mountain of Ben Klibreck and flows north to meet the Atlantic at Bettyhill.) Angus Mackay’s account tells of blood-feuds and battles, not just with other clans but between rival branches of the Mackays themselves. It’s hardly surprising that the name Mackay is said to come from the Gaelic Mhic Aoidh, meaning ‘son of fire’.

By dipping a hesitant toe into these ferocious skirmishes, we find Angus Du Mackay in 1426 (or thereabouts) making a raid on Moray (an old province in north-east Scotland), and later fighting a pitched battle on Harpsdale Hill, about two miles south of Halkirk in Caithness. The motive for these excursions, according to historian Angus Mackay, was revenge for the murder in 1370 of Angus Du’s father and grandfather at the hands of Nicolas, brother to the Earl of Sutherland.

And for many years before that, there was no love lost between the two clans. Angus Mackay explains: ‘Between Iye [Mackay] of Strathnaver and the family of Sutherland there existed a protracted feud, which caused much bloodshed on either side…’

But by 1433 (give or take a few years) things had got much more complicated. A few years previously King James I had summoned the Highland chieftains to his Parliament in Inverness, with the aim of bringing them all to heel, and he had taken Neil Mackay, eldest son of the 7th Chief, Angus Du, as a hostage, imprisoning him on the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth. As a result, when a band of Sutherland men advanced on the Mackays of Strathnaver, the now elderly and frail Angus Du could not send his eldest son into battle with them: that duty fell to his second son, Ian Aberach, who was still in his teens and inexperienced in warfare. What made matters worse was that among the invaders were two cousins of Angus Du – Morgan Nielson Mackay and Niel Nielson Mackay – and they were looking to seize the Mackay lands from Angus Du.

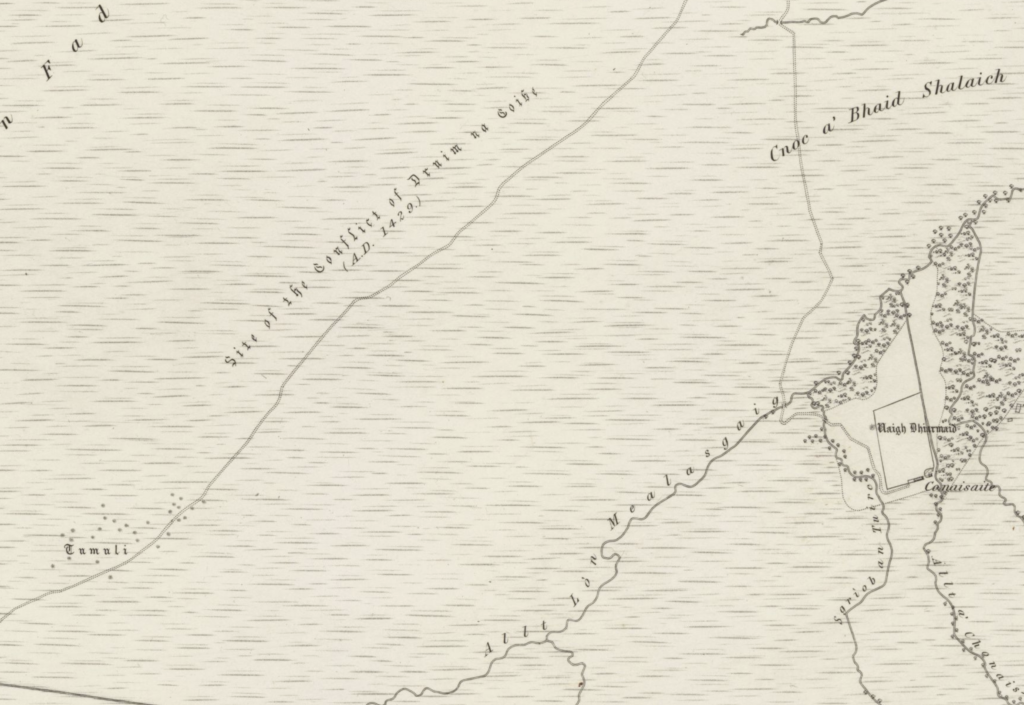

When the two parties got within hailing distance, Ian Aberach was derided by the invaders as a calf on which they would soon put some shackles. But he cleverly led them on, drawing them as far as possible into his father’s territory before giving the order to attack. On a hill called Carn Fada, between Ben Loyal and the village of Tongue, and not far from Caisteal Bharraich, the Battle of Drumnacoub took place.

Section of 6” OS Map of 1878 showing ‘Site of the Conflict of Druim na Coibe’, courtesy National Library of Scotland maps.nls.uk

Section of 6” OS Map of 1878 showing ‘Site of the Conflict of Druim na Coibe’, courtesy National Library of Scotland maps.nls.uk

‘The Mackays, securely posted with their backs to the brae, hurled defiance at their foes and gave them a long-range discharge of arrows.’

Angus Mackay

Then came the hand-to-hand fighting. The Mackays soon drove back the aggressors and killed their leaders, including Morgan and Niel Mackay. The fight turned into a rout, with fugitives fleeing up the slopes of Ben Loyal. Beside a burn that flows into Loch Loyal, according to historian Angus Mackay, ‘a stone marks the graves of the last party killed in the flight.’ Ian Aberach Mackay had triumphed, but at a cost: his ailing father, who had insisted on being borne into the fray on a litter, had been killed by an arrow as he was carried off the field.

Loch Craggie and Loch Loyal

In a paper published in June 1867 in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, James Horsburgh noted that: ‘Beyond Ribegal at Drim-na-coub, where a battle was fought between the Mackays and Sutherlands, are to be seen the graves of those who were killed.’ I wonder if these are the ‘tumuli’ that appear on the map, scattered on the south-western fringe of the battlefield.

There were further battles, and I won’t go into them here, although historian Angus Mackay praises the skilful tactics of Ian Aberach who left no one in any doubt that he was a true ‘son of fire.’ But it seems that he had to watch his back, because several attempts were made to assassinate him. On such occasions, as observed by the Reverend William Mackenzie, he sought refuge in a cave close to Caisteal Bharraich, which became known as Leabaidh Ian Aberich or John of Lochaber’s bed.

In case you are curious, Ian Aberach or Aberich was known as ‘John of Lochaber’ because he had been fostered by relatives of his mother, who was a daughter of Alexander MacDonald of Keppoch in Lochaber. Alexander, in turn, was a son of John of Islay, Lord of the Isles. If Ian’s mother’s name has survived, I have yet to find it.*

Caisteal Bharraich or Castle Varrich (image from Wikimedia)

As for Caisteal Bharraich itself, the structure seems to have consisted of at least two storeys and it is generally assumed that it was once a stronghold of Clan Mackay; Historic Environment Scotland suggests that it is ‘probably a 16th-century reconstruction of an earlier tower,’ and adds that it was abandoned before the 18th century. There is a tradition that the Bishop of Caithness stayed here when he was travelling between his residences at Scrabster and Balnakiel. But castle’s elevated and commanding position, combined with its modest size, have led others to believe that its purpose was largely defensive.

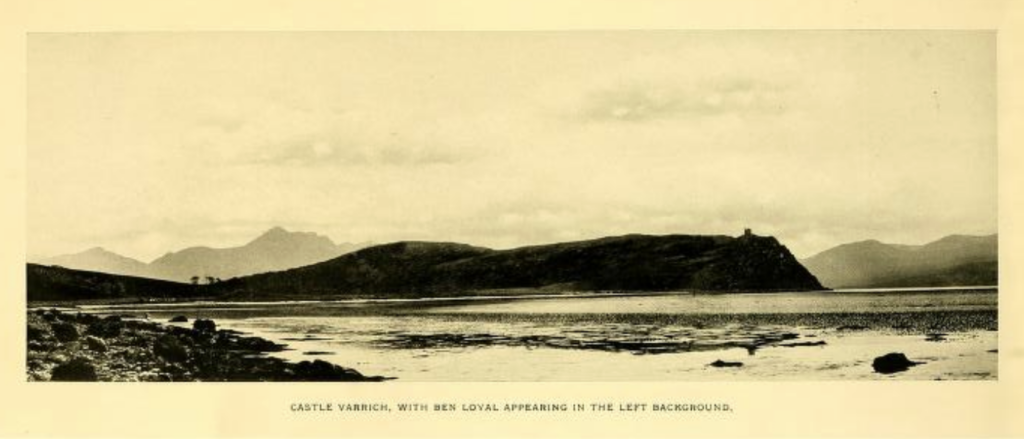

Castle Varrich and Ben Loyal, an illustration which appears in Angus Mackay’s Book of Mackay (1906)

When the east wall collapsed after a storm in 2015, a programme of consolidation work was developed which not only stabilised the structure but incorporated a free-standing steel staircase allowing visitors to admire the magnificent views. The castle re-opened in May 2018.

Now that I know a lot more about its history, I wish we’d taken the opportunity to explore Caisteal Bharraich when we were driving past it in July. However, rain was lashing at the windscreen and we had holiday accommodation to find, so we chickened out. Our one blurred photograph has, however, led me on an interesting trail across the wider landscape, thanks largely to the OS map of 1878…

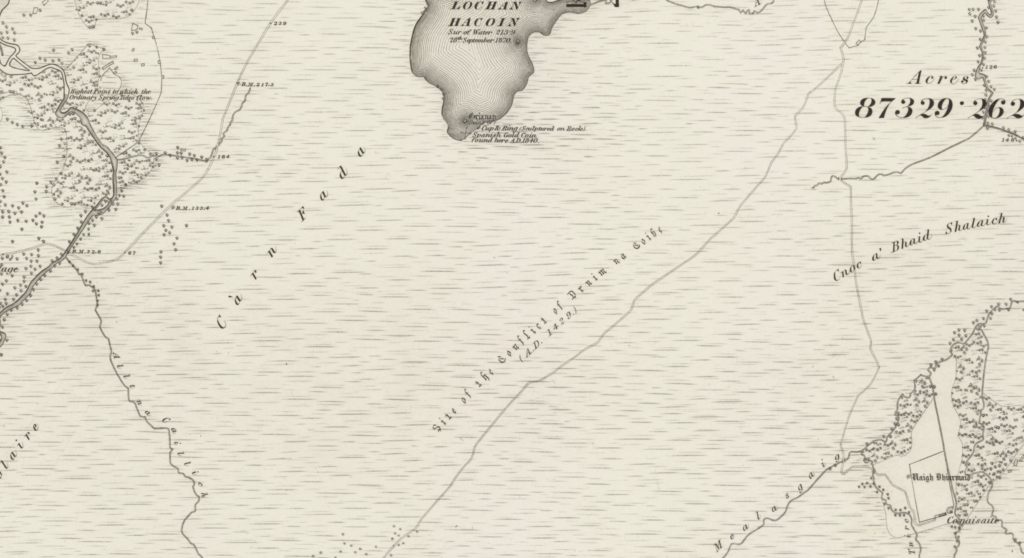

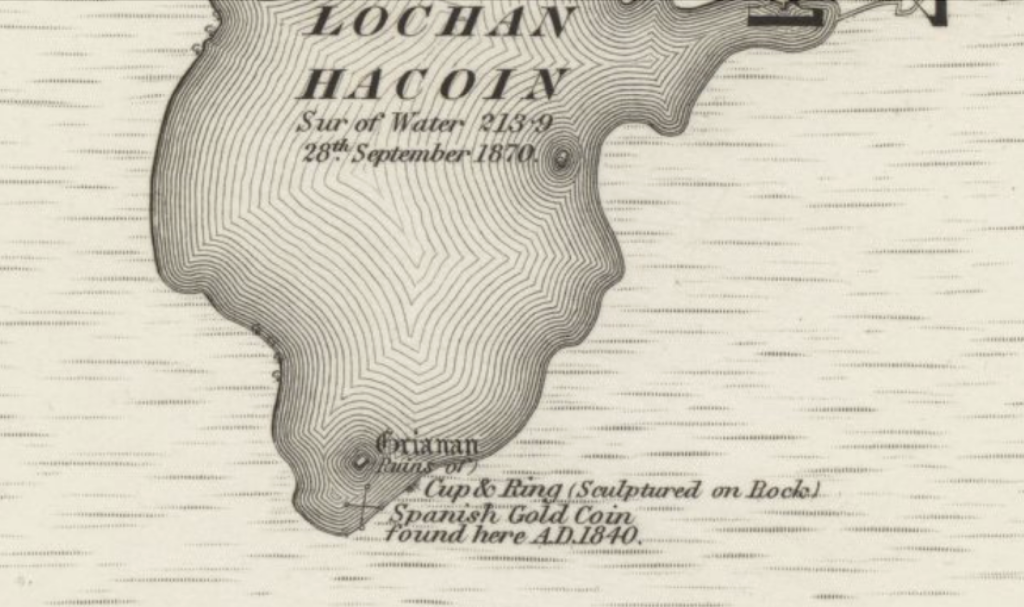

Above and below: Section and enlargement of 6” OS Map of 1878 courtesy National Library of Scotland maps.nls.uk

It begins with the name of Lochan Hacoin (now Lochan Hakel), to the north of the battlefield. The loch is said to be named after a Norse king, and a building on an island in the loch, marked ‘Grianan’ (‘sunny place’) was reputedly his hunting seat. (The island may in fact be a crannog.) A rock on the shore bears cup-and-ring marks, attributed in folklore to the work of fairies who lived on the island; and a cross on the map marks the spot where a Spanish gold coin was found in 1840.

Entries in trove.scot, the new home of the former Canmore database, try to shed some light on this last find, but also raise further questions: ‘A gold coin now in Dunrobin Museum was taken out of Lochan Hacoin… in the cleft of a cow’s hoof. It is Spanish and probably connected with the wreck of an Armada ship, some of whose guns are still at Tongue…’ (1874)

A second paragraph continues: ‘In 1746, the Hazard, a French war sloop carrying money to Prince Charles Edward, was run ashore at Melness… to escape capture by pursuing cruisers. The crew, in trying to make their way south overland with their treasure, were intercepted by the MacKays at Loch Hacon. The Frenchmen, seeing there was no chance of escape, threw the greater part of the money into the loch. Several of the country people found some of it afterwards. (H Morrison, Guide to Sutherland & Caithness, 1883)’

A cow with a gold coin in its hoof sounds like the stuff of Celtic legend, and I’d love to think that this enchanted creature still roams the slopes of Ben Loyal, leading lost and exhausted walkers to the nearest guest house and paying for their board and lodging.

But if I have to accept that the cow willingly surrendered its gold coin, and that it is now in the Dunrobin Museum, the more likely scenario is the second one offered by trove.scot – in other words, that it was part of the supply of gold intended to finance the attempt of Bonnie Prince Charlie to seize the British throne. In March 1746, a French sloop (formerly HMS Hazard, but stolen by Jacobite sympathisers and re-named Le Prince Charles Stuart) was carrying French, Spanish, Irish and Scottish soldiers along with weaponry, ammunition and £13,000 in gold coins for the support of Bonnie Prince Charlie and his followers. Their plan was to put into the harbour of Portsoy in Banffshire and proceed overland to Inverness.

Finding the coast too closely guarded to make landfall, the ship headed north and then west around the top of Scotland and was chased into the Kyle of Tongue by a Royal Navy frigate. The Captain of Le Prince Charles Stuart, a man called George Talbot, hoped that the shallow water of the Kyle would deter the larger vessel from pursuing them further, but instead his ship ran aground on a sandbank, with the Navy frigate still close enough to open fire.

Looking south up the Kyle of Tongue, with Ben Loyal under cloud to the left

A fierce gunfight followed, with the French ship getting the worst of it. In desperation, the survivors on board gathered up everything they could carry, scrambled ashore under cover of darkness and headed south, still hoping to make contact with the Prince. But they had been seen, and even in this sparsely inhabited region there were British government soldiers, among them Mackays under Lord Reay, who knew the country much better than they did. At Drumnacoub, where the Sutherland men and the Mackays had clashed more than 300 years earlier, they were intercepted and arrested.

Most of the gold was seized and shared among Government supporters. But there are stories that the fleeing Jacobites threw some of it into Lochan Hakel or buried it somewhere around the Kyle of Tongue. Had it reached the Prince before Culloden, he might at least have been better able to feed, equip and pay his exhausted men. But instead he suffered a crushing defeat and was soon running for his own life, leaving behind a legacy of devastation and retribution.

Maps are wonderful things, especially when they preserve old place-names that have legends attached to them. There’s a further story I want to mention: just to the east of the battlefield of Drumnacoub is a spot marked as Uaigh Dhiarmaid or Diarmaid’s grave.

This is a legend that has been told for centuries: Diarmaid O’Duibhne belongs to the Fianna, the renowned band of warriors led by Fionn Mac Cumhaill. He is young and honourable, but he is blessed – or perhaps cursed – by a ‘love spot’ on his forehead which makes every woman fall in love with him. He usually keeps it hidden beneath a cap, but at a feast held to celebrate the betrothal of Fionn Mac Cumhaill to Gráinne, daughter of the High King of Ireland, Gráinne glimpses Diarmaid’s love spot, and is instantly smitten.

Heedless of her pledge to marry Fionn, Gráinne pours a sleeping draught into the other guests’ wine, places the protesting Diarmaid under a ‘druid bond’ which was effectively an oath to do her bidding, and runs away with him. But it isn’t long before Fionn and the Fianna wake up, and then they are hot on their trail, so that the fleeing couple can never rest more than one night in the same place.

Eventually Gráinne wins the reluctant Diarmaid’s heart, and she becomes pregnant; but their time together is drawing to a close. One night, as they sleep at the foot of a hill, Diarmaid hears the hounds of the Fianna baying in the distance and makes his way towards them, inevitably meeting the still-vengeful Fionn.

Fionn gives Diarmaid a challenge. A ferocious wild boar is rampaging about the hill, having escaped the spears of the huntsmen. Fionn knows that Diarmaid is fated to be killed by a wild boar, and Diarmaid is too courageous to refuse. The boar charges at Diarmaid and breaks his sword; after a vicious struggle, Diarmaid strikes it dead with the hilt. But Fionn insists that Diarmaid measure the length of the boar by walking along its spine with his bare feet; and then Diarmaid, too, is close to death, his foot pierced by one of the beast’s poisonous bristles, with Gráinne weeping over his body and Fionn trying – but not hard enough – to bring him life-giving water from a nearby spring.

On Ben Loyal (in Gaelic, Beinn Laughail), this fateful encounter is said to have taken place. A scar on the northern face of the mountain is known as Sgrìob an Tuirc, ‘the furrow of the boar,’ gouged by its tusks as it fell.

In his hauntingly beautiful book, The Bone Cave: A Journey Through Myth and Memory, published in 2023, Dougie Strang recalls how he located Diarmaid’s grave by referring to the OS map of 1878. He describes it as a long, unremarkable mound colonised by yellow hawkbit, its shape reminiscent of the upturned keel of a boat whose prow points towards the northern spur of Ben Loyal. Although his logical mind craved the knowledge that comes from an archaeological excavation, he recognised ‘that such an act would be a violation, a contract broken between place and story.’

I love the concept of a contract between place and story, and it is a rare and precious thing to come across instances where that contract has survived.

Strange to find Diarmaid so far from his ‘home’ – but where is his home, exactly? Only because I’m familiar with Glen Lonan, where there is another ‘Diarmaid’s grave’ (close to Tòrr an Tuirc, the knoll of the boar) do I assume that his homeland is in Argyll. But Glen Shee claims him too: his story is preserved in place names around Ben Gulabin,** and there is another Diarmaid’s grave in Kintail, by the shore of Loch Duich. Over in Ireland, Diarmaid’s memory is woven into the landscape of Ben Bulben in County Sligo.

I guess the answer is that Diarmaid’s story lives and is carried in our minds – Dougie Strang speaks of the ‘carrying stream’ not just as a geographical feature but as a current that holds the life force of these legends, maintaining their essence while allowing them to evolve. And as for Diarmaid himself, resting – or so we imagine – within earshot of the battle of Drumnacoub, he might have felt some kind of kinship with the ‘sons of fire.’

Ben Loyal (centre) and Ben Hope (under cloud to the right)

Quite a rambling story this time! If you’ve visited Caisteal Bharraich yourself, or Diarmaid’s grave for that matter, I’d love to hear from you.

A more detailed telling of Diarmaid and Gráinne’s story is in my blog post on the stone circle and standing stone in Glen Lonan.

Footnotes

*If you’ve researched this history and can tell me the name of Ian Aberich’s mother, please get in touch.

** Ben Gulabin features in my book, Britain’s Landmarks and Legends.

Reference

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Historic Environment Scotland blog, Dec 2018: Caisteal Bharraich – a Small Landmark with a Big History

- Highland Historic Environment Record

- Trove.scot: Caisteal Bharraich

- Trove.scot: Lochan Hakel

- The Castles of Scotland

- The Restoration of Caisteal Bharraich

- Angus Mackay, The Book of Mackay (1906)

- Dougie Strang, The Bone Cave: A Journey Through Myth and Memory (2023)

- Culloden Battlefield: The Skirmish of Tongue

- Caithness Field Club Bulletin, 5 April 1983: An Eighteenth Century Sea Battle in the Kyle of Tongue

- James Horsburgh, ‘Notes of Cromlechs, Duns, Hut-circles, Chambered Cairns, and other remains, in the County of Sutherland’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Nov 1867

Photos (unless specified otherwise) copyright Colin and Jo Woolf

9 Comments

ROBERT HAY

Good God Jo, you’ve given us enough of a story there to keep our brains whirling for a month. Who would have guessed that bleak inhospitable area had so much going for it in romance and history.

Totally cut off from other parts of Scotland it was like a foreign country.

Jo Woolf

I know, Bob, I didn’t mean it to be so long but it just kept growing! 😂 I had no idea there were so many stories either – it was a total surprise to find out about the ‘Skirmish of Tongue’. And a coincidence that Dougie Strang whose book I was reading had actually found and slept by Diarmaid’s grave. That’s a book that you might enjoy yourself.

Bob Hay

Yes Jo, we tend to forget that centuries ago Northern Scotland was part of a great Scandinavian trade bloc. They blithely and confidently carried on in their own Scandocentric world. And there again, looking at Neolithic Orkney you could say the same.

Lucky for them Mercator’s Projection hadn’t been invented yet.😀

Jo Woolf

Very lucky! 😂

davidoakesimages

I am glad I bookmarked that post to read later.. task now completed. What a great read, just hope I can remember it all 🙂 But I also had a chuckle on the quote ” Angus Mackay’s account tells of blood-feuds and battles ” wasn’t it always that way, or so it seems…. but also because we had a neighbour for a good number of years (at times it seemed too many), her name was Mary Mackay and boy! was she aggressive and itching for a fight (verbal of course)… but that is another story 🙂 🙂

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, David – I admit it was a bit of an epic! Oh my goodness, Mary Mackay sounds like a true ‘daughter of fire’!

davidoakesimages

She was…..

Finola

Wonderful post! We also have many tales of Diarmuid and Gráinne and many places name Leaba Diarmuid agus Gráinne. Here’s a taste: https://roaringwaterjournal.com/2023/02/12/romantic-toe-head/ The part that made me laugh was “A cow with a gold coin in its hoof sounds like the stuff of Celtic legend, and I’d love to think that this enchanted creature still roams the slopes of Ben Loyal, leading lost and exhausted walkers to the nearest guest house and paying for their board and lodging.” In my experience of Celtic legend the cow would have been far more likely to lead walkers to their doom.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Finola! I had missed that post by yourself and have just read and enjoyed it. Ah well, you know how legends evolve! This particular Celtic cow has seen the error of her ways and wants to be hospitable!