The old pinewoods in Glen Orchy

Standing outside on these dark mornings, when there’s no wind and the sea is so still that the lights on the island of Luing are reflected in the water, you can hear the clatter of dead leaves coming down off the trees, colliding with branches and other leaves in their path with a noise like running footsteps, or some unseen creature moving through the darkness of the wood. Sometimes there’s just one, but the next moment there are more – stirred by a vagrant breeze perhaps, abandoning their grip in unison to tumble haphazardly onto the damp ground.

And then a tawny owl calls from a few fields away, immediately answered by another, and some distant geese set up a clamour that rises and falls like a wave, breaking and settling back into the stillness. Before long the robins wake up, sending out little staccato notes of surprise before offering their first tentative trills to the slowly lightening sky.

It was on this kind of morning, encouraged by a forecast of broken cloud, that we decided to head off into Glen Orchy.

For about ten or eleven miles – although it seems much longer – the River Orchy tumbles over a succession of falls and rapids, flanked on both sides by woods of birch, alder and oak as well as commercial forestry plantations of Sitka spruce mixed with larch. Bare hillsides rise steeply up to the skyline, while the only road – narrow, with passing places – hugs the bottom of the glen, never far from the river, so that glimpses of deep pools and or cascading white water can be seen through the trees.

Following a route that I’d seen on the excellent Walkhighlands website, we parked by a bridge over Eas Urchaidh (the Falls of Orchy) and walked up a forest path, stopping every other minute to watch the clouds lifting off the hills, or to look at the myriad tiny droplets of water that were afloat in the air, illuminated momentarily by the sun. In fact, the cooled air was so saturated that every surface glistened with thousands of beads, catching the light now for the first time and flashing with fire. Next to a burn that was rushing to join the main river, a birch tree was festooned with bejewelled cobwebs, visible as you walked in the sunlight but quickly fading when you stepped back into shadow.

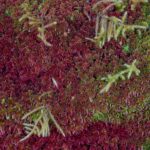

On one side of the track, likely the side that doesn’t get so much sun, sphagnum mosses were rampant, in particular the ruby-coloured variety, and all kinds of fungi were either sprouting from the trunks of trees or pushing up through the leaf litter like a miniature forest. Colin is fascinated by them all, and quickly got wet knees as he angled himself to take photos. Blue tits were twittering around the trees, no doubt looking to feast on the spiders whose webs had been so beautifully exposed. The changing light was just mesmerising. At this rate, we’d be lucky to get back by nightfall!

The track winds upwards at a gentle rate, and after about an hour or so of slow going we arrived at the fenced reserve of Allt Broighleachan. Big old Scots pines with their crusty, pinkish-red trunks lifted their heads above brilliant yellow birches, with lower-growing junipers around their feet, and everywhere a rusting tangle of once-rampant bracken. We forded a burn, which was still flowing strong after the rains of last week, and began climbing again, up a path that was now running with water and distinctly boggy in places.

The views began to open out, revealing big expanses of bog myrtle, blaeberry and heather and the light golden flanks of surrounding hills. To the northwest we could hear the bellowing of stags, and we stopped to try and make them out on a distant ridge. Through binoculars, we watched one stag advancing on another that seemed to be guarding a small group of hinds. The challenger was chased off with more haste than dignity, while the hinds grazed on.

According to Tony Dalton, writing in True Tales from the West Highlands and Islands, ‘sometime in the eleventh century a band of Mac-an-leisdears [sons of the arrow maker] settled in Glen Orchy, where they became arrow makers to Clan MacGregor.’ He explains that the Gaelic word leisdear, pronounced ‘leshjer’, had been anglicised into ‘Fletcher’ by the 18th century.

The birch woods of Glen Orchy are said to have provided material for the Fletchers’ skilled hands, as recalled in this traditional poem (which I’ve quoted in a previous blog post):

Bogha a dh’iubhar Easragain

Sioda na Gaillbhin

Saighead a bheithe an Doire-dhuinn,

Ite firean Locha Treige

Bow of the yew of Easragan

Silk of Gallvinn

Arrow of the birch of Doire-donn,

Feather of the eagle of Loch Treig.

There are stories of bloodthirsty raids and battles connected with the MacGregors and their adversaries but it doesn’t seem quite right to go into them here, when there was so much beauty and serenity in the day. But there’s an interesting tradition that the Fletchers ‘were the first to raise smoke to boil water in Glenorchy,’ which gave them a claim on the land.

Having seen this lovely remnant of old woodland, it’s easier perhaps to imagine what the country might have looked like before humans started to make a noticeable impact: woodland groves interspersed with more open country, trees growing to maturity and then falling where they stood, their dead trunks giving support and shelter to other forms of life. There’s a wonderful sense of nature flourishing and responding to the changing seasons, vibrant and diverse and resilient.

We watched a pale half-moon setting over the hill and then turned to retrace our steps, leaving the stags to their roaring, which would probably carry on into the night. Miraculously, we kept our feet dry on the walk back down. I can still smell the rich, fragrant dampness of it all, and I want to keep it somewhere safe in my mind for the short winter days.

Reference

- Clifton Bain, The Ancient Pinewoods of Scotland (2013)

- Tony Dalton, True Tales from the West Highlands and Islands (2016)

- Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, The Peat-fire Flame (1937)

- Walkhighlands – Allt Broighleachan pinewood

Photos copyright Jo and Colin Woolf

10 Comments

K Brooks

Your photos are beautiful; they take me there.

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much! That’s lovely to know.

Zee

The photos are worth wet knees (and more) and the narrative is simple and compelling. Thank you for sharing and taking us along on your walks.

Jo Woolf

Colin thought so, anyway! Thank you, and I’m very glad you enjoyed it.

Finola Finlay

A walk in a true wood like this is a balm to the soul. Your words and photographs are a perfect homage to place.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Finola! You’re so right, that’s exactly what it felt like. I’m glad that such places still exist.

Richard Miles

A fascinating blog Jo.Good to see those fine veteran Scots pines which are fragments of the Caledonian forest .They are fairly abundant on the many small islands in Loch Maree.

You reference Alastair Alpine McGregor whom my grandmother new quite well.She used to recite poetry in English and Scottish Gaelic which fitted in with McGregors interest in Scottish folklore .I just about remember her powerful Scottish East coast accent.

Richard Miles

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Richard! Yes, those big old pines are magnificent. Fascinating to hear that your grandmother knew Alasdair Alpin MacGregor. It sounds as if she had some tales to tell herself! I’d love to have heard her reciting the poetry.

ROBERT HAY

Simply beautiful Jo. Any more words woould be superfluous.

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much, Bob! Hope all is well with you.