Book review: ‘The New Sylva’

In 1664 the horticulturalist John Evelyn published a book called ‘Sylva – or, A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber in His Majesties dominions.” This was the first printed book to be published by the Royal Society, of which Evelyn was a founding member; and it was also the world’s first comprehensive study of trees.

In 1664 the horticulturalist John Evelyn published a book called ‘Sylva – or, A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber in His Majesties dominions.” This was the first printed book to be published by the Royal Society, of which Evelyn was a founding member; and it was also the world’s first comprehensive study of trees.

This year, exactly 350 years after ‘Sylva’ was printed, a modern-day version has been released; and over the last couple of weeks I have had the delight of reading it.

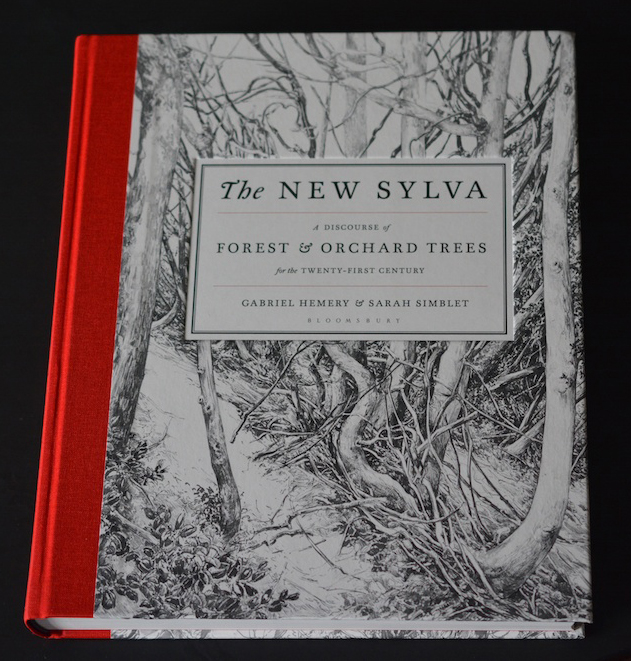

“The New Sylva – A Discourse of Forest & Orchard Trees for the Twenty-First Century” is written by Gabriel Hemery and illustrated by Sarah Simblet. It’s clear just how much of a challenge this would present to any author, just by its very nature… but it is also obvious, right from the start, that for Hemery and Simblet this was a labour of love.

[ “Illustrated with over 200 exquisite drawings, The New Sylva describes the tree species that play a significant role in today’s society, and offers a deep and enriching understanding of our orchards and forests.” ]

Even before I had unwrapped ‘The New Sylva’ from its clear cellophane cover, I knew that this was going to be a book to treasure.

Although eager to read about the tree species, I got pleasantly lost for a while in the historical background to Evelyn’s original work. It was written in the reign of Charles II, in response to concerns about Britain’s dwindling resources of timber for shipbuilding – and with good reason. I learned, for example, that it took 1,200 trees to build the Mary Rose, pride of Henry VIII; the felling of these trees alone would have cleared 75 acres. Between 1730 and 1789, Britain’s shipyards consumed about 8,000 oak trees per year.

Since that time, we have done very little to make amends:

“About half of the ancient woodlands in Britain that survived until the 1930s have been lost to development or otherwise damaged… Those that remain are mostly small and fragmented.”

An ancient woodland is one that has been in continuous existence since 1600 in England and Wales, and 1750 in Scotland. Sadly, it is all too easy to overlook the importance of this unique habitat – and it’s not just the trees themselves that are at risk:

“Native tree species generally tend to support greater biodiversity, compared with introduced trees… our native oaks support more than one hundred times more invertebrate species than sweet chestnut.”

I was shocked to read that, during the last century, over 40 species of animals, insects and plants that lived in Britain’s broadleaved woodlands have become extinct.

Instead of promoting a campaign of pure conservation, Hemery says we must also encourage genetic diversity within a species: this allows healthy variation and an increased resistance to disease. He also recommends maintaining a diversity of species and structure in our woodlands, using systems of continuous forest cover rather than clear felling. He believes that “…building resilience in future forests will be a decisive factor in our ability to help wildlife adapt to environmental change.”

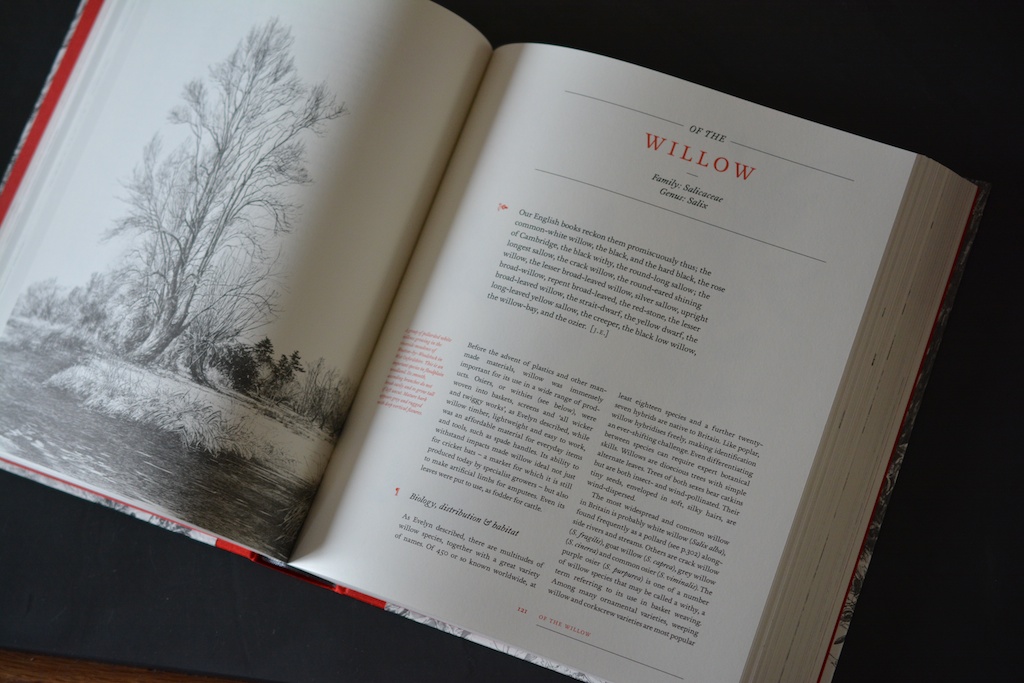

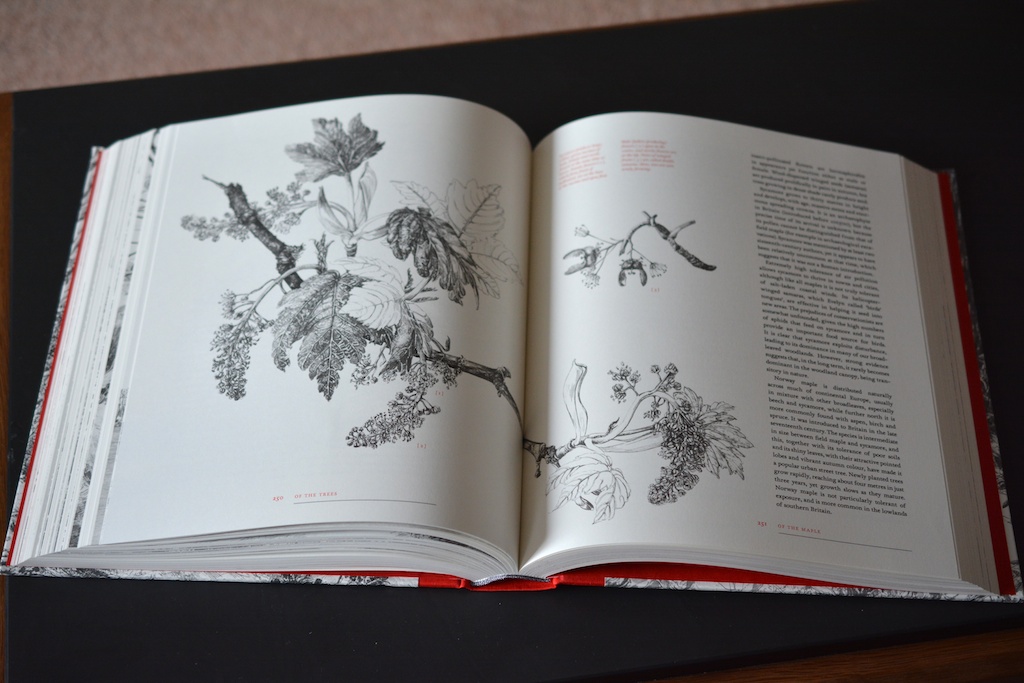

Progressing to the species themselves is like wandering into a forest and stopping by every single tree in turn, to examine it in wonder (except that you’d never find all these species together in a single wood!) Oak, birch, ash, holly, pine, juniper… the trees that colonised Britain after the last Ice Age are joined by comparative newcomers such as horse chestnut, plane, poplar and larch. Over 100 species are described in total, and we learn about their characteristics, their distribution, the conditions they need to flourish and the diseases that affect them.

Progressing to the species themselves is like wandering into a forest and stopping by every single tree in turn, to examine it in wonder (except that you’d never find all these species together in a single wood!) Oak, birch, ash, holly, pine, juniper… the trees that colonised Britain after the last Ice Age are joined by comparative newcomers such as horse chestnut, plane, poplar and larch. Over 100 species are described in total, and we learn about their characteristics, their distribution, the conditions they need to flourish and the diseases that affect them.

There are even tips on cultivation and management: at first I thought these would appeal mainly to foresters or estate managers, but after a paragraph or two I was absorbed in a landscape that sounds like Thomas Hardy’s Wessex with its coppices of chestnut and hazel, pollarded ash trees, and orchards of apple, pear and damson. You realise the truth in Hemery’s observation that “being a forester is akin to running the slowest relay race, the baton changing hands after decades or human lifetimes.”

‘The New Sylva’ has been designed to echo its predecessor in terms of structure and content. The clear and authoritative text is sprinkled with quotes from John Evelyn; it’s almost as if the great man is listening in on the conversation and offering gems of wisdom from the comfort of an armchair. He advises that the coppicing hazel trees is best done after a full moon:

“…cut your trees near to the ground with a sharp bill [hook], the moon decreasing”;

and he accurately foretells a bright future for the plane tree, which was still uncommon in Britain in 1664…

“I am persuaded, that with very ordinary industry, they might be propagated to the incredible ornament of the walks and avenues to great men’s houses.”

What makes this book so lovely is that you can dip into it at random and discover fascinating little facts: the aspen (Populus tremula), is one of the few species that can be identified by sound alone, as its leaves tremble in the breeze; and some of Scotland’s oldest larch plantations owe their existence to the Dukes of Atholl, who brought seed from Austria in the 18th century and even fired it through a cannon to disperse it across inaccessible slopes.

What makes this book so lovely is that you can dip into it at random and discover fascinating little facts: the aspen (Populus tremula), is one of the few species that can be identified by sound alone, as its leaves tremble in the breeze; and some of Scotland’s oldest larch plantations owe their existence to the Dukes of Atholl, who brought seed from Austria in the 18th century and even fired it through a cannon to disperse it across inaccessible slopes.

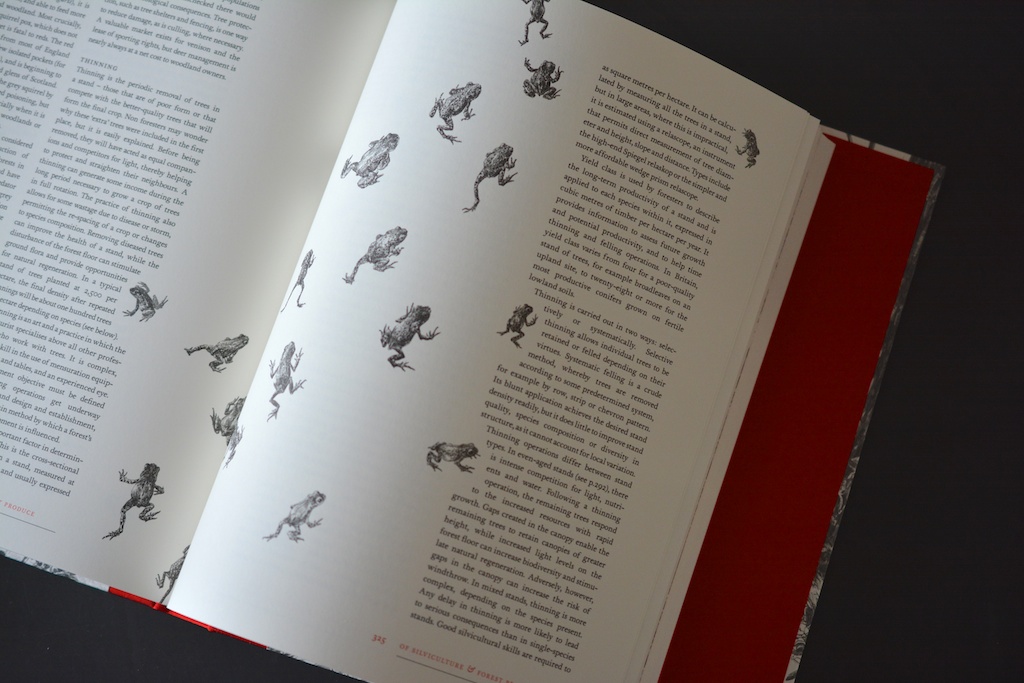

The illustrations are carefully observed and beautifully executed. Sensitive pen-and-ink drawings of trees in the landscape are accompanied by studies of leaves, catkins, blossom, fruit, seedlings, bark… even the wildlife that they support. There are moths, birds and wild flowers, armies of little frogs and delicate feather details.

This is a weighty volume but it is a delight to handle, being printed on lovely thick paper with an excellent quality binding; the layout is clean and simple, with touches of old-fashioned typefaces that evoke Evelyn’s original text.

“Trees are intertwined with humanity. They supported the cradle of civilisation and frame all of our lives.”

‘The New Sylva’ is a real treasury of woodland wisdom, and I know I shall be dipping into it regularly, both for pleasure and for reference. This is a book to cherish for generations – but I hope it will also be used as an educational resource, re-connecting our children with the lore and science of trees.

This video from YouTube shows Gabriel Hemery examining the book for the first time:

‘The New Sylva’ by Gabriel Hemery and Sarah Simblet

Hardback, 400 pp, 11.5 x 9.5 inches, published by Bloomsbury Publishing. Priced at £50 (postage free within UK). Read more at www.newsylva.com.

Talking to Gabriel Hemery…

Gabriel Hemery is Chief Executive of The Sylva Foundation, a charity whose mission is to revive Britain’s wood culture. He very kindly agreed to answer some of my questions about ‘The New Sylva’:

Whose idea was it to publish a successor to John Evelyn’s ‘Sylva’, and what were your guiding principles in creating a modern-day version?

The original concept was mine. It stemmed from creating the Sylva Foundation as a charity in 2009 – which I co-founded – as a vehicle to promote the management of forests along sustainable development principles. I was mindful that 2014 would be both the 350th of Evelyn’s Sylva, and the fifth birthday of the Sylva Foundation. Writing an updated version of Evelyn’s landmark work seemed a good idea, both to celebrate the original and to introduce the concept – of what we call in the Sylva Foundation our wood culture – to a modern audience. Planning started for the book in 2011.

The book contains an amazing breadth and depth of knowledge. How long did it take you to do the research?

The whole ‘project’ took over three years. From the original idea to create a book the steps involved meeting Sarah Simblet and shaping early ideas with her, to developing a book proposal, working through a literary agent to attract publishers (we were lucky to have four bidding for it), and sealing the book deal with Bloomsbury Publishing – all took about one year. Research and writing took about 18 months solid, plus a further six months of copy editing, proof reading and so on. In another sense, the ‘research’ for the book entailed all my professional experiences as a forest scientist (or silvologist) to date.

We’re always hearing about worrying new diseases or development schemes that threaten the existence of ancient woodlands. What do you think poses the greatest danger to our native trees?

Firstly, in my view the sooner we can embrace a wider perspective on the notion of ‘native’ the better for the future of our forests. In one sense, I think the obsession with ‘native’ is a significant threat if it clouds both judgement as to what qualifies a healthy forest, and one that is sustainable – i.e. deliver long-term benefits for mankind and nature.

I think the single greatest threat to our trees is man! Either directly through development (e.g. loss of land) and industry (e.g. global trade in plants), or third hand through man-made environmental change. Helping our forests adapt to change is conceivable, protecting them from the inevitable impacts of change is not.

A more technical answer, and perhaps in too much detail, would be as follows. We need to embrace genetic diversity – both within species (i.e. accepting that we should explore introducing/embracing non-native genetic material of a native species), and sometimes where appropriate, other species including non-native if a forest is to thrive. At some point, the latter choice may even need to apply to our ancient woodlands if the climate warms as much as projected for 2080.

What message do you believe ‘The New Sylva’ will bring to readers in the 21st century? And how do you think John Evelyn would view it?

My ambition in writing The New Sylva was to introduce the wonders of forestry to a modern audience, including the lay person. Those involved in forestry will know that it has transformed itself many times in the last century alone. As society has become ever distanced from the natural world, less is understood by members of the public about how we now care for our forests. The term ‘sustainability’ was introduced by a forester and forestry has led the way in developing sustainable practices – it is an amazing ‘industry’ or sector in how it balances the needs of man with that of nature.

I hope that the book will reconnect people with our forests and with wood in deep and meaningful ways, so that once again everyone can celebrate the beauty of a living tree and its gifts both during its life and after it has died. Ultimately this means that the sound of a chainsaw in a forest should be greeted* – it means that the forest is being managed and that nature’s wonder material – wood – will be made available as an alternative to our man-made CO2-producing materials.

*There’s a caveat here of course: the assumption here is that I am talking about forests in Britain, elsewhere in Europe and in the developed world where sustainable forestry practices are applied; it does not apply to illegal logging in tropical forests.

I would hope that John Evelyn would be immensely proud of his legacy, and that even 350 years after his book was published that he was continuing to inspire others to follow in his footsteps. In terms of the book, I think he would be amazed by the beautiful illustrations made by my co-author Sarah Simblet, who after all uses no materials unavailable to artists in the 17th century. Technically, in some areas he may be surprised at quite how little practices have changed – even how some knowledge has been lost. I hope he would be intrigued and excited by the many practices now at play in our forests, the depth of our scientific understanding and the myriad of new products that we are able to produce from wood. ❀