Dunadd: behold the king!

If we could hold back the soft curtains of time for a few minutes and glimpse the hilltop fort of Dunadd as it was about 1,300 years ago, we might witness a ceremony that shaped the history of Scotland.

If we could hold back the soft curtains of time for a few minutes and glimpse the hilltop fort of Dunadd as it was about 1,300 years ago, we might witness a ceremony that shaped the history of Scotland.

On a flat slab of rock just below the summit a footprint is carved in shallow relief. As he gazed across the lands that were his by blood and sword, a new ruler of Dal Riata would place his foot in this hollow and swear to protect his people against all invaders. An abbot of Iona – Columba himself, perhaps – was there to bless the king and witness the oath.

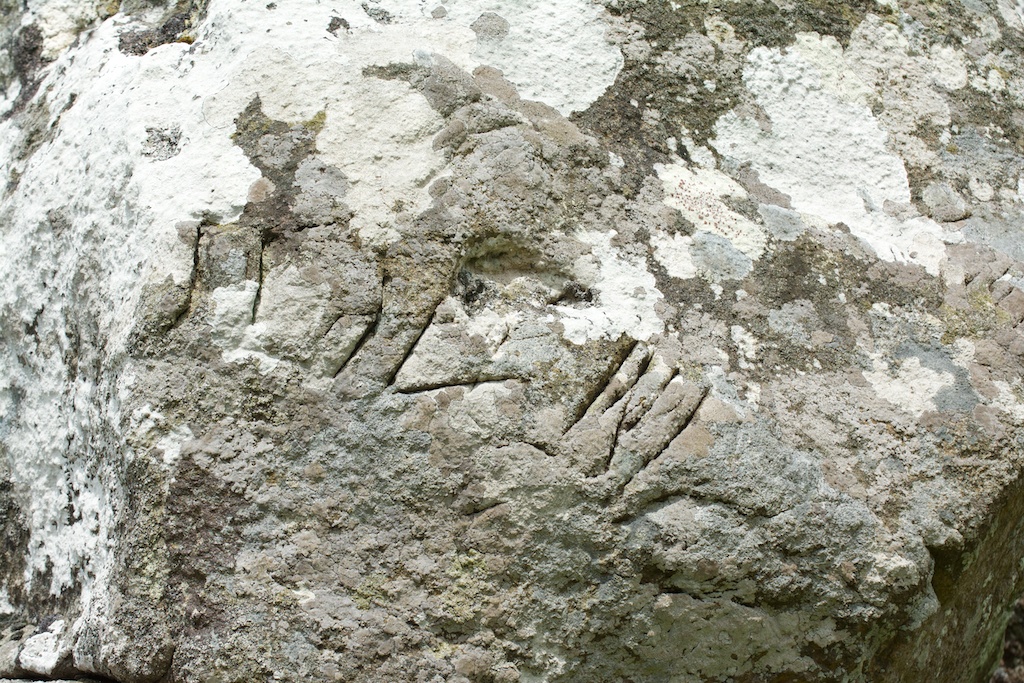

That much we think we know… the rest is conjecture. Close by, the faint image of a boar, carved in Pictish style, and two lines of Ogham script have a significance which we can only grasp at like straws in the wind. A second footprint, now hard to see except in slanting light, was carved a good stride behind the first; and a couple of yards away a small boulder has been hollowed out, perhaps for use as a basin. What did it contain? What was dipped in it?

That much we think we know… the rest is conjecture. Close by, the faint image of a boar, carved in Pictish style, and two lines of Ogham script have a significance which we can only grasp at like straws in the wind. A second footprint, now hard to see except in slanting light, was carved a good stride behind the first; and a couple of yards away a small boulder has been hollowed out, perhaps for use as a basin. What did it contain? What was dipped in it?

The low rocky mound of Dunadd captures your gaze as you travel north from Tayvallich through the ancient landscape of Kilmartin Glen. Below it, the River Add, from which the fort gets its name, snakes around in lazy curves through the flat peatland of Moine Mhor, the ‘great moss’, before flowing out to sea. A couple of whitewashed farmhouses nestle around its base, and away to the south are the oak woods that mark the beginning of Knapdale.

But if you were visiting Dunadd 2,000 years ago, you wouldn’t have arrived by land at all. The site was first chosen as a natural fortress around 300 BC, and at that time the sea would have lapped at its feet. How do we know? Scientists have measured the gradual uplift of the land since the last ice age, a natural reaction after the weight of ice was finally removed; and pollen samples taken from the surrounding peat have allowed them to measure fairly accurately the rate at which the island became a peninsula and then a landlocked hill. Today, the sea lies a couple of miles to the west.

But if you were visiting Dunadd 2,000 years ago, you wouldn’t have arrived by land at all. The site was first chosen as a natural fortress around 300 BC, and at that time the sea would have lapped at its feet. How do we know? Scientists have measured the gradual uplift of the land since the last ice age, a natural reaction after the weight of ice was finally removed; and pollen samples taken from the surrounding peat have allowed them to measure fairly accurately the rate at which the island became a peninsula and then a landlocked hill. Today, the sea lies a couple of miles to the west.

Whatever significance Dunadd might have had to the first inhabitants of Kilmartin – the shadowy people who set up the stones of Nether Largie and Temple Wood and buried their people in the chamber at Dunchraigaig – its status in the early 6th century seems to have taken a huge leap up, thanks to the arrival of some new settlers. These were the Gaels, also known as the Scoti or Scots.

Whatever significance Dunadd might have had to the first inhabitants of Kilmartin – the shadowy people who set up the stones of Nether Largie and Temple Wood and buried their people in the chamber at Dunchraigaig – its status in the early 6th century seems to have taken a huge leap up, thanks to the arrival of some new settlers. These were the Gaels, also known as the Scoti or Scots.

Who were the Gaels?

Most historians believe that the Gaels came from Ireland, just 20 miles across the sea, perhaps spurred by the need for more land or the desire to expand their territory. Curiously, their nickname, ‘Scoti’, has roots that stretch back beyond memory, to the legends that describe the birth of Ireland’s people.

Most historians believe that the Gaels came from Ireland, just 20 miles across the sea, perhaps spurred by the need for more land or the desire to expand their territory. Curiously, their nickname, ‘Scoti’, has roots that stretch back beyond memory, to the legends that describe the birth of Ireland’s people.

“…Scoti also had unfavourable connections. For some users of the word it meant something like ‘pirates’ – and it holds within it an echo of a time when these people were viewed, at least by someone else, as marauders who came from the sea.” Neil Oliver, ‘A History of Scotland’.

The Gaelic kingdom of Dalriada encompassed parts of Ireland and much of western Scotland from Kintyre right up to Ardnamurchan and Lochaber; and for its people, Dunadd became a prime focus of ceremony and power.

“Dunadd has produced the largest, most diverse range of imported pottery of any site in the Celtic West.” Historic Scotland

We can sense the wealth of the people who came to Dunadd through the things they left behind. Precious metals were worked here – gold and silver, as well as copper, lead and tin. Findings include fragments of moulds for penannular brooches, sherds of crucibles, pieces of pottery and glass, and a 7th century garnet and gold jewel of the quality found at Sutton Hoo. Traces of orpiment, a yellow mineral used for painting illuminated manuscripts, have also been discovered – evidence, perhaps, that the occupants of Dunadd were recognising the teachings of Christianity. Did the monks of Iona obtain their pigments here as they worked on the Book of Kells?

We can sense the wealth of the people who came to Dunadd through the things they left behind. Precious metals were worked here – gold and silver, as well as copper, lead and tin. Findings include fragments of moulds for penannular brooches, sherds of crucibles, pieces of pottery and glass, and a 7th century garnet and gold jewel of the quality found at Sutton Hoo. Traces of orpiment, a yellow mineral used for painting illuminated manuscripts, have also been discovered – evidence, perhaps, that the occupants of Dunadd were recognising the teachings of Christianity. Did the monks of Iona obtain their pigments here as they worked on the Book of Kells?

There is also the interesting possibility, fuelled by the writings of the Anglo-Saxon chronicler Bede, that Northumbrian kings might have sought refuge at Dunadd when their lives were endangered by their own people.

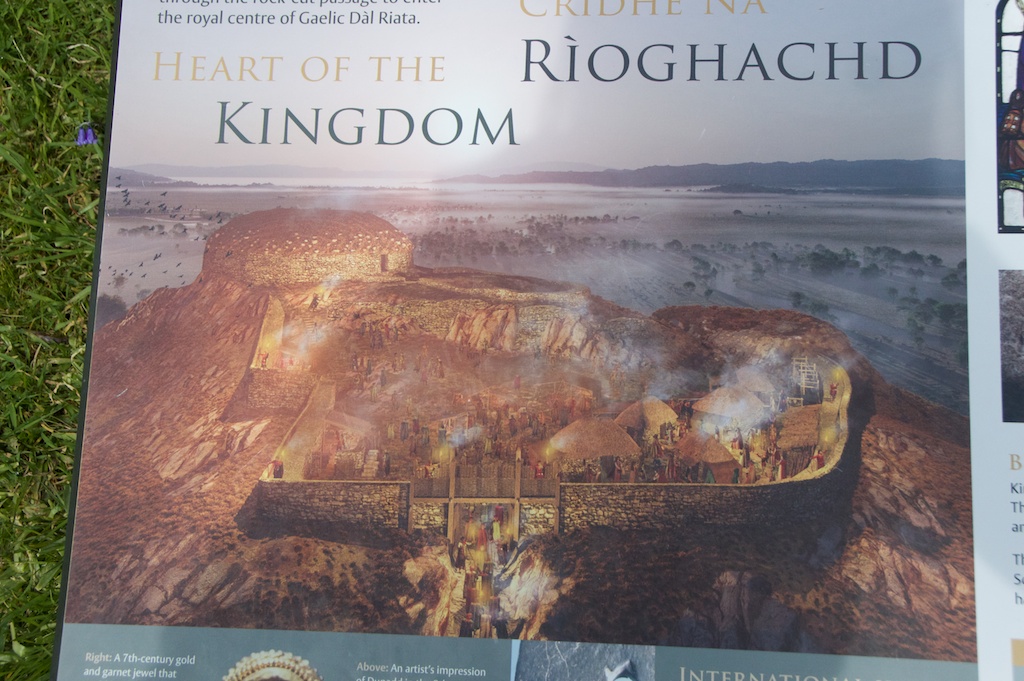

I photographed the illustration on one of the information boards at the site, because I think the artwork is fantastic. It shows the fortress alive with the light of fires and humming with people. In the distance, the woods and salt marshes stretch away towards the Firth of Lorn.

The fortifications at Dunadd were wrapped around the summit of the hill in successive layers so that visitors must have had the impression of progressing through three or four distinct tiers before they gained the king’s presence. Natural passages in the rock were enhanced to make an easily guarded gateway, and you still get a sense of entering a special place as you walk up there. Ruined ramparts and the remnants of buildings can be made out, and there’s a well, now seemingly dried up, whose water – according to legend – used to rise and fall with the tide.

“When kings of Dal Riata placed one foot in the footprint to be inaugurated, they were betrothing themselves to the land that fed their people. In Ireland, where six such royal footprints are known, records claim that the stone recognises and proclaims the rightful king.” Historic Scotland

“Tradition says that this is the footprint of Oisin or Fergus Mor Mac Erca, the first King of Dál Riata who died in 501… Colmcille [Columba] is said to have taken part in the inauguration ceremony of King Aidan here at Dunadd in 574.” St Columba Trail

It’s impossible to resist imagining the ceremonies that took place here. But we know so little. To me, the footprint looked small enough to be a child’s, although records say that it’s approximately a size seven. Try as I might, I couldn’t make out the full extent of the boar carving – you probably need the slanting light of morning or evening to photograph it successfully. The Ogham symbols continue to baffle archaeologists as to their meaning.

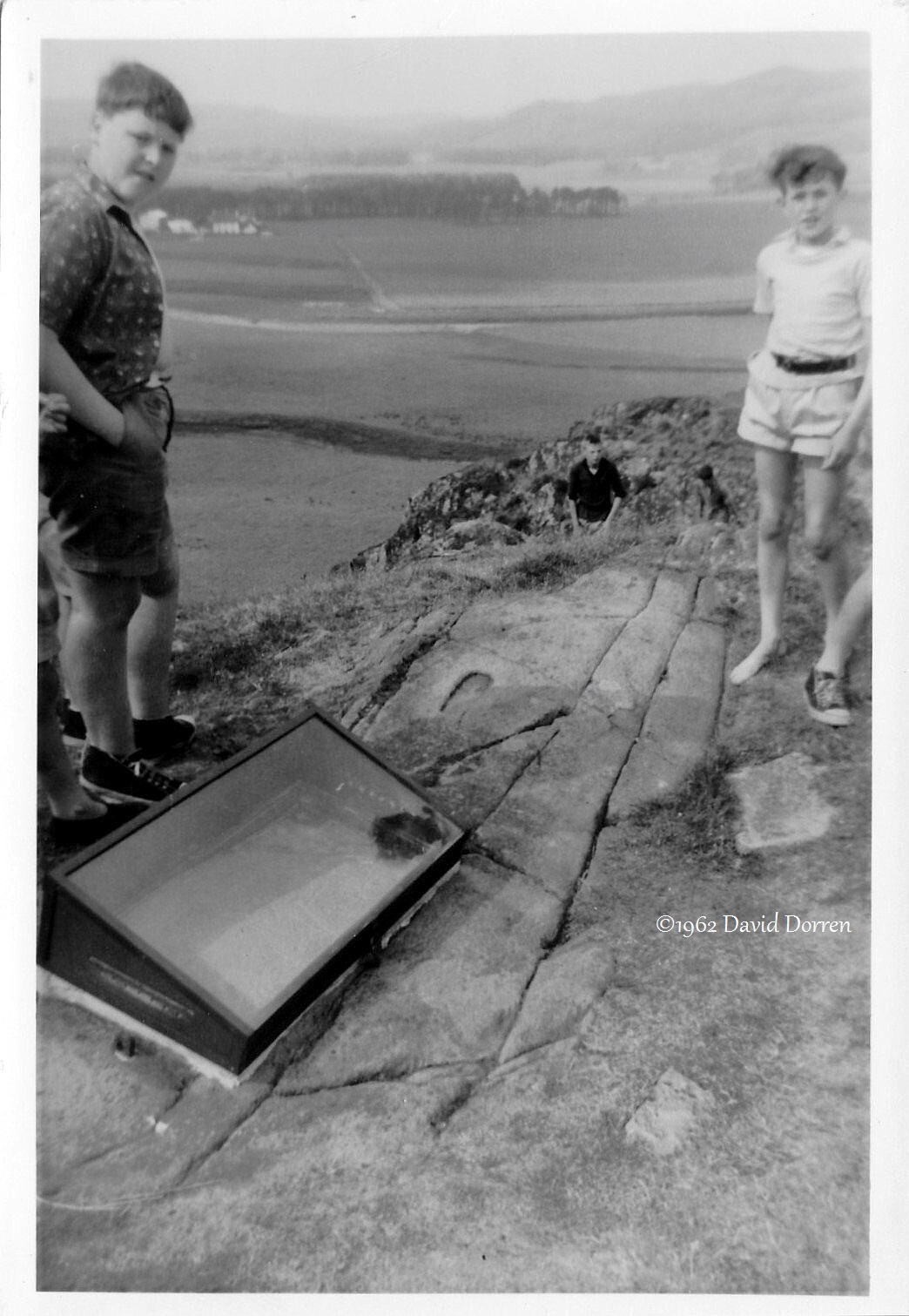

And then I learned something else, half-remembered from reading ‘A History of Scotland’, which I dismissed as being impossible the first time I heard it. In recent years, Historic Scotland has carefully placed a replica slab – complete with carvings – over the top of the original one, after laser-scanning it and preserving it with a protective layer. This was necessary to protect the old stone from constant erosion, as increasing numbers of visitors were naturally tempted to try their own feet for size. I would imagine that lichens were also beginning to obscure the carvings.

And then I learned something else, half-remembered from reading ‘A History of Scotland’, which I dismissed as being impossible the first time I heard it. In recent years, Historic Scotland has carefully placed a replica slab – complete with carvings – over the top of the original one, after laser-scanning it and preserving it with a protective layer. This was necessary to protect the old stone from constant erosion, as increasing numbers of visitors were naturally tempted to try their own feet for size. I would imagine that lichens were also beginning to obscure the carvings.

I’m a bit ambivalent about this. I can fully appreciate the decision, because no one wishes to see a unique part of Scotland’s heritage being worn away. The work has been done exceptionally well, and after all the original footprint is still there, in its original spot. But at what stage in time will someone think it’s safe to remove the top layer and expose the old stone again? It’s always a compromise, I can see that… but part of me wishes that we didn’t have to make it.

While I was taking photos from the summit, Colin was wandering around the lower slopes in search of wild flowers and insects. He stumbled upon a carving that he first thought was graffiti, but I’m not so sure. It looks like Ogham to me. It’s on a vertical rock face, above head height. It would be so good if it said ‘mind your head‘ in Ogham! If you are an expert on this period of history, I’d be grateful for your opinion.

While I was taking photos from the summit, Colin was wandering around the lower slopes in search of wild flowers and insects. He stumbled upon a carving that he first thought was graffiti, but I’m not so sure. It looks like Ogham to me. It’s on a vertical rock face, above head height. It would be so good if it said ‘mind your head‘ in Ogham! If you are an expert on this period of history, I’d be grateful for your opinion.

Just like the tide, with every rise there has to be a fall. In the Annals of Ulster it is recorded that Oengus, son of Fergus, King of the Picts, seized Dunadd in 736 AD; and although this may not have been the end for Dunadd, and it may well have been regained by the Scots, it was a sign that change was coming. In the late 9th century Dalriada and Pictland were absorbed into the newly powerful kingdom of Alba; the details are hazy, and the process can’t have been peaceful, but the result was that the old Pictish centres of Scone and Dunkeld were preferred to Dunadd. By this time, anyway, the island of Dunadd was probably being reclaimed by the land, making it appear more vulnerable. Some sources state that the Stone of Destiny, upon which all British monarchs are still crowned, was taken from Dunadd to Dunstaffnage for safe keeping, and then moved to Scone.

Just like the tide, with every rise there has to be a fall. In the Annals of Ulster it is recorded that Oengus, son of Fergus, King of the Picts, seized Dunadd in 736 AD; and although this may not have been the end for Dunadd, and it may well have been regained by the Scots, it was a sign that change was coming. In the late 9th century Dalriada and Pictland were absorbed into the newly powerful kingdom of Alba; the details are hazy, and the process can’t have been peaceful, but the result was that the old Pictish centres of Scone and Dunkeld were preferred to Dunadd. By this time, anyway, the island of Dunadd was probably being reclaimed by the land, making it appear more vulnerable. Some sources state that the Stone of Destiny, upon which all British monarchs are still crowned, was taken from Dunadd to Dunstaffnage for safe keeping, and then moved to Scone.

Dunadd may not have been abandoned immediately. British Archaeology says that “one radiocarbon date suggests use of the summit as late as the 11th/13th century”, and the site was still important enough to warrant the reading of royal proclamations here in 1506.

The kings and their court have long gone, and the priests and the goldsmiths, the cooks and servants and the splendid visitors with their rich robes and jewels, but the sense of purpose is still here. At midsummer, with a cuckoo calling from the oak woods across the marsh and the scent of bluebells and hawthorn drifting on the breeze, Dunadd holds you in its thrall.

The kings and their court have long gone, and the priests and the goldsmiths, the cooks and servants and the splendid visitors with their rich robes and jewels, but the sense of purpose is still here. At midsummer, with a cuckoo calling from the oak woods across the marsh and the scent of bluebells and hawthorn drifting on the breeze, Dunadd holds you in its thrall.

Visiting Dunadd

Dunadd is in the care of Historic Scotland, and is open all year; admission is free. To get there, follow the A816 north from Lochgilphead for a few miles and keep an eye open for the signpost which directs you down a narrow road to a car park by the river. You’ll see Dunadd from the main road.

After that, you can drive a bit further north and explore all the other archaeological wonders of Kilmartin Glen!

More information about visiting can be found on Historic Scotland’s website.

Postscript, 20th July 2015:

I am very grateful to Dr David Dorren for sending me this wonderful photo from 1962, which was taken when he visited Dunadd with the Dunoon Scouts. It shows the original rock surface, and a glass case which was being used to protect some of the carving. Amazingly, this case was first installed in 1928. Copyright © David Dorren.

Sources:

- Historic Scotland

- ‘A History of Scotland’ by Neil Oliver

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland

- BBC History

- St Columba Trail

- British Archaeology

- The Heroic Age: Sea Level Change Around Dunadd and Dumbarton Rock

Photos copyright © Jo Woolf

More ancient sites in Kilmartin Glen and nearby…

21 Comments

oglach

Loved this. I’m no historical expert, but according to some Scotland was named after a princess of Egyptian birth, named Scotia, who led her people from Egypt to Ireland, where some of them eventually moved on to Scotland. This may seem very fanciful to most, but the interesting thing is, according to the Human Genome Project, there exists a gene marker (named Dalcassian Type III) which exists only in human beings from the Dalcassian regions of Ireland (Tipperary and Limerick, mainly) and Northern Africa. (I’m reciting from a poor memory, so you’ll have to check that for yourself.) If any of that is true, it stands to reason that the early Irish inhabitants of Scotland intermarried with it’s natives, and their cultures became intertwined. As for what you assume to be Ogham (I’ve not visited the site myself), if it’s on a vertical pillar, then that’s what it is, at least in some form. Some Ogham can be easily deciphered; the examples that cannot are thought by some to be a sort of musical score written based on the teachings of Pythagoras. Again, fanciful, but we’ll see. Thanks for the piece and the lovely photos.

Jo Woolf

Thank you so much for your detailed comment and fascinating info. I had read that about Scota or Scotia, but I didn’t know about the genetic research – I will be looking that up now! How amazing. That’s a wonderful idea about some Ogham being a musical score – and why not, after all? Sound must have played a great role in ceremonies, as it still does. There is so much we have forgotten, despite our modern technology. Thank you again for your insight and suggestions.

oglach

The thanks goes to you.

Haydyn Williams

Increasingly we are able to decipher Pictish ogams.The issue is that they are using Sengaeilge/Old Irish, mixed in with Brythonic (similar to Welsh) ,and even Old Norse (as at Bressay – Shetland,which is now fully decipherable). For the most part they follow a simple formula “A son of B”,so they are commemorative. There is,according to Dr Katherine Forsyth of Glasgow University a Clear personal name in the ogam at Dunadd,so it seems to be following the regular pattern. There are no musical ogams that I have encountered in my 28 years of study of them…sorry to kick that novel idea. Also,not sure the Stone of Scone was ever there. It certainly wasn’t ever in Ireland,and definitely not at Teamhair. The last mention of the stone at Teamhair is 1019,3 years after the death of Brian MacCennedi. The first mention of the Scone stone is in 2 14th century Scots Chronicles,and the first english source to mention dates from the mid sixteenth century. Lia Fail also never meant “Stone of Destiny”. That is an erroneous translation of the sengaeilge/old Irish. Fail is a shortening of Faileas,which is a place. It it were to mean “Destiny” the word required would be “ciniúint”.

Jo Woolf

Thank your for sharing your insight, Haydyn. I am glad to know that Pictish ogham is gradually being deciphered.

tearoomdelights

A splendid collection of photos, Jo. It is a pity about covering over the original stone. I suppose the new stone gives the same sense of history and it does look as if it’s been very well done, but I can’t help feeling that some connection with the heritage is lost if the original is hidden under a replica.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Lorna! Yes, I know what you mean about the original stone. It’s a compromise, and I can understand the reasons behind it – it’s better than it being removed and placed behind glass somewhere. But part of me would love to have it exposed to the rain and the wind and the air, just as it was for hundreds of years before. We can’t arrest time, that is the thing – however much we try to slow it down.

David McNaught

Great article Jo. It’s certainly a special place to visit that still commands a powerful draw on your imagination. I remember reading somewhere that the ‘graffiti ‘ Colin came across may be just that, runic script left by a marauding Viking..Easy to imagine the longships making a target of Dunadd. Did you come across the replica carving of the boar in the cottage garden as you climb up the hill. Easier to make out and gives you more of a mental picture of what your looking at when trying to identify the real thing. I was there in January, when the low sun helped in picking out the details of the carving. Loved the artists impression of the fort, I’d always tried to imagine how it would have looked. Have to get back there again one day. Dave.

Jo Woolf

That’s very interesting about the Viking ‘graffiti’, David! No, I must have missed the replica boar carving – I could see it on the information board by the stone itself, and that helped to a certain extent, but I could only make out the legs! Yes, wouldn’t Dunadd have been a spectacular sight when it was occupied? Fantastic. It really fires your imagination – you feel as if those long-lost ancestors are almost close enough to touch. Thank you for your comment!

justbod

Another great article Jo! Love the photos and love your writing style – a magical mix of facts and your own observations, ideas and musings! Great article and another place to add to the ever growing ‘must-visit’ list!

Jo Woolf

That’s very kind of you, Justbod! It’s such a pleasure to share these places. Dunadd is very special, and I’ve been wanting to get there for a long time. Kilmartin Glen is one of those extraordinary landscapes where you really feel as if you’re making contact with the past.

Colin MacDonald

Great post, last time I visited Dunadd it was just me and my wife, and a tribe of sheep inhabiting the upper tiers of the site. Incredible to think of Dunadd as an important cultural and political centre when you look at it today, time has certainly passed it by and there is a sadness about it. Although the area is depopulated today, you really get a sense of how militarised Argyll must have been when you look at the hundreds of Duns that existed in all the nearby hills.

In regards to the preservation of the foot print, I was always a little confused as to what exactly had been put over the top of the original rock. Is it a very thin protective layer, like a ‘skin’, or is it larger copy placed over the top of the original to completely cover it? I was never quite sure. I do think it is necessary though to protect it, it’s one of our great (and underrated) cultural treasures.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Colin! Yes, it would be so good to see the area as it was populated in early medieval times. It certainly takes a leap of imagination to see Dunadd as it was, surrounded by water, and bristling with defensive walls. In 1978 the footprint stone was covered by a concrete replica with a protective layer between the two. The replica stone was raised in 2009 (I think) to check on the condition of the original, and to laser-scan it. I guess the artificial surface does protrude slightly above the level of the hilltop but it doesn’t look unnatural. It certainly is one of our cultural treasures, and in one of my favourite parts of the world!

Colin MacDonald

So have I got this right in saying, that the original footprint stone is still there on Dunadd, underneath the replica and that the original wasn’t totally removed in 2009?

Jo Woolf

Yes, that’s true – it lies beneath the replica, still in situ. When the preservation experts checked it in 2009 they were happy with the condition of it, according to a news report.

McEff

Interesting, that, Jo. I first read about Dunadd many years ago in a book by (I think) Geoffrey Ashe called The Quest for Arthur’s Britain. It’s a period of history which is all the more fascinating because the facts are so sketchy.

Alen

Jo Woolf

Yes, very true, Alen – the mystery really has an allure about it! I am interested too in the origins of the Stone of Destiny. Was it the real piece of the Lia Fail that was given to Edward I or a cover from a cess pit that the monks palmed him off with?!

Thomas Gavin (@thomasjohngavin)

Nicely put together, enjoyed haveing a look, always wanted to go, maybe this summer, like the pictures too! Seems like someone has already mentioned this but the “Stone of destiny” that was taken away by Edward’s army is known not to be the real one, when tested it was found to be local Perth sandstone – the real stone of destiny’s origin is middle eastern and made from granite (Stone of Jacob) with inscriptions. Obviously the people who hide the stone couldn’t have been left alive to retrieve it!!

Jo Woolf

Hi Thomas, thank you and I hope you are able to visit Dunadd this summer! Yes, the Stone of Destiny – what an enigma! There’s one rumour that the monks at Scone gave Edward I a stone cover from a cess pit. A wonderful mystery about the whereabouts of the original!

Susan Campbelly

Fab report on Dunadd, such an atmospheric place. Your photos show just what it’s like being there, and the description really conveys the location and information as far as it’s known. No matter how often I visit Dunadd or Kilmartin glen, it has the same effect; sensing the history of people all down the ages coming there for amazing occasions. ☺️

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Susan! I’m glad you enjoyed this. Dunadd was such a wonderful place to visit. Yes, Kilmartin is very special – you can feel it, but you can’t really put it into words.