Loch Nell: the Tomb of the Giants and a Serpent Mound

“And now we were in the very midst of a land of legends.”

R Angus Smith, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1879)

Early on a Sunday morning in July, with a shimmering haze promising later heat, it seemed like a great idea to go dowsing along a serpent mound by Loch Nell. There were only two potential drawbacks to this plan: one, I’m still a beginner at dowsing, and two, I was not entirely convinced that the serpent mound existed.

But, having consulted the trusty database of Canmore, which plots all known archaeological sites on a zoomable map, I was sure at least that the remains of a chambered cairn could be inspected; and I knew that the views would be beautiful, regardless.

So from Kilmore we took the minor road that winds its way up Glen Lonan – the ancient Road of the Kings – and parked beneath some trees at the south end of Loch Nell, where a tiny crannog is lapped by gentle waves.

I had another reason for wanting to visit this quiet inland loch that is known mostly to fishermen. The chambered cairn had been kind of calling to me ever since I learned that it was, at one time, known as ‘the Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn’. How can you know this, and not want to look for it?

Fionn and the Fianna…

Not for the first time, we’re blurring the boundary between history and legend. In Irish mythology, which spread at one time across Scotland, the landscape was peopled with giants – heroic warriors whose great deeds were immortalised in stories told by elders and bards, handed down by word of mouth to successive generations. The stories were of love and lust, hope and despair, victory and loss. Characters were often shape-shifters, possessed of superhuman qualities or magical powers. One of the main protagonists was Finn or Fionn MacCumhaill, leader of a warrior band known as the Fianna, and hence some of the stories are known as the Fingalian legends. One story, which has echoes of King Arthur, says that Fionn never died but instead lies sleeping in a cave, surrounded by his warriors. When the hunting horn of the Fianna is sounded three times, he will rise again. So you can see how deliciously tempting it is to imagine that a cairn known as ‘the Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn’ is his secret resting place.

Loch Nell can appear gloomy and uninviting but that morning it was a blissful summer blue, a breathless, bottomless realm in which woods and clouds and hills were mirrored with crystal clarity before a warm wind stirred them into the abyss. We climbed over a gate and headed up through a field of reedy grass and bracken, feeling the heaviness of the heat on our backs. The chambered cairn was easy to spot, as its light-coloured stones stood out against the green hillside. And it was certainly impressive. Perched on a group of boulders set upright, the surviving capstone is so huge that you wonder at the effort of getting it there. The space beneath was too tight to crawl into, even if I’d wished, and was filled with ferns, grasses and foxgloves.

At one time, heaped stones would have covered this burial chamber, but over the centuries the mound has been scattered and lost. The bare structure of the grave itself is all that remains. During an excavation which took place in 1970, it was discovered that the chamber had been divided into two compartments. Sherds of Neolithic pottery, flint flakes and fragments of beaker vessels were discovered. Cremated bones and a food vessel were also found in cists that had been dug into the cairn, representing subsequent burials.

We noticed that the upper surface of the top stone was plastered with birds’ droppings, bleached even whiter by the sun. White feathers were scattered in the hollow and a smashed eggshell lay close by. Perhaps ducks or geese had been nesting there; quite fittingly, I later found this reference to the Gaelic name of Loch Nell:

“The name is poetic, Loch-a-neala, the lake of the swans; there may have been many such birds here once, but they are gone.”

R Angus Smith, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1879)

I sat and admired the glorious view across Loch Nell and then thought about my dowsing rods. This wasn’t the easiest terrain to dowse, as I kept stumbling into deep hollows hidden by the long grass, and it was as much as I could do to encircle the mound while focusing on the rod. It dipped at regular intervals throughout the circumference, suggesting lines of energy converging on the centre and creating a star-like pattern in my mind.

Looking across the first cairn towards the second (directly above it), with the serpent mound visible as undulations in the bright green bracken

A couple of hundred yards off, a second cairn was visible as a low grassy mound which has been hollowed out – the result of an excavation, according to one account, conducted in 1871 by a Mr J S Phené. Emerging from it, I could make out a low, sinuous shape in the landscape that seemed to bend around some clumps of willow, heading in the direction of the loch.

Above: The second cairn, looking south-east over the end of the loch

The second cairn had obviously been opened, but a lot of its covering was still in place. In between the rocks, wild flowers had woven summer garlands of fragrant thyme, delicate pink stonecrop, bright yellow tormentil and feathery grasses. Dowsing had become all but impossible by that time, because of the lumpy terrain underfoot; winter might be a better time, when it’s easier to see where I’m putting my feet. I did detect what I thought might be some kind of flower pattern around the burial mound, but I was more interested to see a single hazel tree, unusually exposed and solitary, leaning in towards the mound. Drawn by the energy, or driven by the weather? The south-westerly gales could well play a part, but I couldn’t see any other trees that were similarly shaped. It had a good crop of nuts, too.

The second cairn, with attendant hazel (above and below)

So were we looking at a serpent mound or a natural geological formation? Some sources have suggested that the curving shape is an esker, caused by the deposited sediment of streams that were flowing inside glaciers. When the glacier retreats, the ground beneath is revealed with its ‘ghosts’ of long-gone streams. When choosing their site for a burial, Neolithic people may have deliberately positioned the cairn and joined it to the esker so that it created an S-shape. Alternatively, the entire structure may have been man-made.

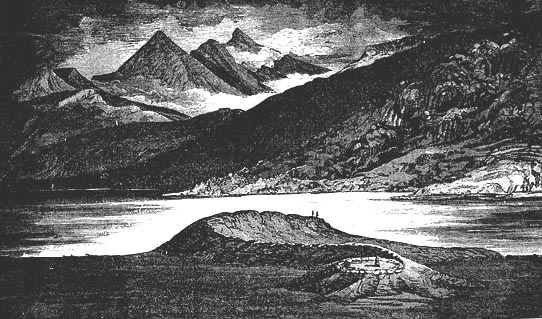

In 1883, the Scottish travel writer Constance Frederica (‘Eka’) Gordon-Cumming published a fascinating account of her visit to the “Great Dragon” by Loch Nell, which she describes as being “wonderfully perfect in anatomical outline.” The ground beneath her feet was much less overgrown at the time, and by removing some of the peat-moss and heather she found “that the whole length of the spine was carefully constructed with regularly and symmetrically-placed stones at such an angle as to throw off rain…” This feature, she believed, had been instrumental in preserving the structure from erosion. She could see that the “spine” was a long narrow causeway, “made of large stones, set like the vertebrae of some huge animal.” On the burial mound – which she calls the “head” – she found a circle of stones “exactly corresponding with the solar circle as represented on the head of the mystic serpents of Egypt and Phoenicia, and in the great American Serpent Mound.” Emanating from the head, “diverse small ridges… may have represented the paws of the reptile.”

Drawing of the serpent mound, from Constance F Gordon-Cumming’s ‘In the Hebrides’

Gordon-Cumming also points out that the burial cairn and serpent mound seem to have been carefully positioned so that someone standing on the burial mound

“…would naturally look eastward, directly along the whole length of the Great Reptile, and across the dark lake, to the triple peaks of Ben Cruachan. This position must have been carefully selected, as from no other point are the three peaks visible.”

‘In the Hebrides’ (1883)

Even before reading her account, we noticed that the peaks can be seen through a relatively narrow gap in the hills when you’re standing on the cairn and looking across the serpent mound.

View over the cairn and serpent mound with the peaks of Cruachan visible in the distance

View over the cairn and serpent mound with the peaks of Cruachan visible in the distance

The Victorians loved the idea of druids making bloody sacrifices, and Gordon-Cumming is obviously influenced to some extent by these imaginary scenes, as she alludes to “white-robed priests” making offerings on the “mystic altar.” She discusses the serpent myths of various cultures worldwide, and reveals some interesting details about the Loch Nell mound, such as the local tradition that in times past it was a place of public execution. She also details the items found during the 1871 excavation, namely human bones, charcoal and charred hazelnuts. “Surely the spirits of our Pagan ancestors must rejoice to see how faithfully we, their descendants, continue to burn our hazel-nuts on Hallowe’en, their old autumnal Fire Festival, though our modern divination is practised only with reference to such a trivial matter as the faith of sweethearts!”

From the same era, another writer, Dr R Angus Smith, whom I quoted earlier, is inclined to dismiss the serpent mound idea as sentimental nonsense. In ‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’ (1879), he recalls his visit to Loch Nell and it is to him that I owe my first discovery that the chambered cairn was known as “the tomb of the giants, and of the Finn.” But Smith, obviously writing from a logical historian’s point of view, gives his opinion that there is “not even a faint reason” for the continuance of this myth. Additionally, although he acknowledges that among the Celts the serpent was “a very interesting animal”, and he admits that many ancient cultures revered them, he sees no reason to accept the idea of “saurian worship” by the side of Loch Nell. In the same paragraph, however, he recounts a relatively recent story about a man who, while fishing on a local loch, saw an eel passing by beneath his feet in the morning, “and it passed all the time he was there, and when he returned in the evening there it was still passing, so that it must have been a very long sea-monster.”

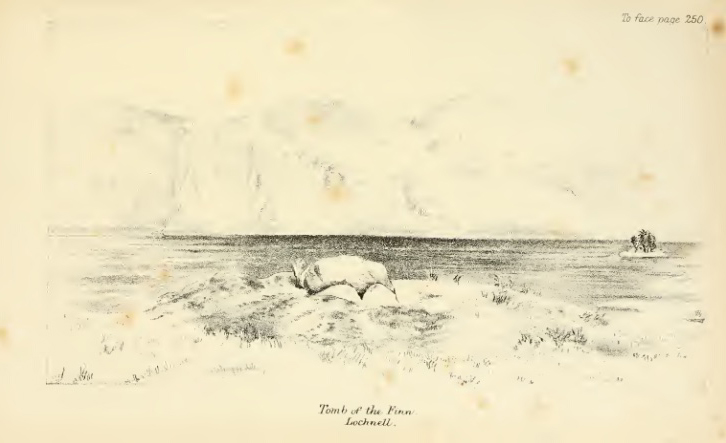

R Angus Smith’s report was illustrated with drawings by his niece, Miss J Knox Smith. This one is captioned ‘Tomb of the Finn, Lochnell’.

R Angus Smith’s report was illustrated with drawings by his niece, Miss J Knox Smith. This one is captioned ‘Tomb of the Finn, Lochnell’.

I love the stories and experiences that are preserved in Smith’s book. It was written at a time when visits to such places as Loch Nell involved procuring a horse and cart from somewhere like Oban, and asking directions at cottages or farmhouses along the way. Smith was not alone – he took with him several friends, and often describes their conversations about the places they visited. If they found something they wished to excavate, they didn’t hesitate to do so, earnestly but not always very thoroughly – which is probably a mercy. It is the kind of stuff that would give modern conservationists recurring nightmares, but there’s an innocent curiosity about it, a genuine desire for learning and an enjoyment of intellectual discussion.

Having rowed out to Loch Nell’s two crannogs (there is a second at the northern end), Smith dug down into the southernmost one and found the ashes of burnt peat, along with bones, charcoal and nuts. He was satisfied that he had found a “lake-dwelling” which had once been surrounded by a wall. Interestingly, he also revealed that Loch Nell had its own inundation story:

Having rowed out to Loch Nell’s two crannogs (there is a second at the northern end), Smith dug down into the southernmost one and found the ashes of burnt peat, along with bones, charcoal and nuts. He was satisfied that he had found a “lake-dwelling” which had once been surrounded by a wall. Interestingly, he also revealed that Loch Nell had its own inundation story:

“Stories had been told us of a buried city which was submerged by the floods that made the lake, and of which parts could be seen on a clear day. It was also said that there, on the larger of the islands of this loch, the Campbells of Lochnell lived in former times.”

After inspecting the crannog, cairns and (dubious-looking) serpent mound to his satisfaction, Smith continued his exploration of the loch shores and the track beyond. He was obviously in his element. He wrote:

“Every mound here has an artificial look, and one almost expects to find history at every step.”

I know exactly how he felt.

Tales of Glen Lonan…

The chambered cairn is not alone in having a traditional connection with Fionn MacCumhaill. A little further up Glen Lonan is a standing stone known as Diarmuid’s Pillar. According to the story, in later life Fionn was engaged to be married to Gráinne, daughter of the High King, but at their betrothal feast Gráinne fell in love with Diarmuid, one of Fionn’s young warriors. Determined to wed him instead, Gráinne gave a sleeping potion to the guests and the two lovers ran away together. Eventually Gráinne’s foster-father negotiated peace with the outraged Fionn, but that wasn’t the end of the story. Diarmuid was doomed by a prediction that he would be killed by a boar, and despite knowing this, he joined a boar-hunt organised by Fionn. When Diarmuid was mortally wounded by the animal, Fionn alone had the power to save his life by allowing him to drink water from his hands, but he allowed the liquid to slip through his fingers, and Diarmuid died. The standing stone is said to mark his grave.

The version given by Dr R Angus Smith is that the water was brought “in the hands of the most beautiful women, to make the cure certain; but the ladies could not manage to bring any – the way was long and rough and the day was hot, so that before they arrived their hands were empty.” Although he notes that “it is said in Ireland that Diarmid was buried on the Boyne”, he admits that around Loch Nell there was a persistent local sentiment that this was his last resting place:

“…when some persons lately were looking for a stone kist in this place which is called his grave, a poor woman going by said, in great anxiety, ‘Oh, oh, they are lifting Diarmid.’ He is not forgotten yet.”

Legend or history? Is there any difference, or more importantly, was there any difference to the people who knew and loved these stories? We won’t find the physical remains of Fionn or Diarmuid by Loch Nell. As the bards would probably tell us, they are in the water slipping through our fingers, in the wind-blown feathers of departed wildfowl, in the splashing of a fish that is heard but not seen.

Footnotes:

Constance Gordon-Cumming refers to the Serpent Mound in Ohio, which is now described as the largest serpent effigy in the world, believed to have been built around 321 BC. I have found reports of serpent mounds elsewhere in the UK, including Skelmorlie in Ayrshire, and Rotherwas in Herefordshire. However, they still seem to be little-known features that will probably continue to inspire much debate.

Glen Lonan lies along the ancient ‘Road of the Kings’, the route taken by funeral processions bringing the king’s body across country for burial on Iona.

Here is an interesting clipping from the Oban Times, reprinted in Jackson’s Oxford Journal, a weekly paper, on 25th November 1871:

The Serpent Mound at Lochnell—Mr John S Phené, F.G.S., F.R.G.S., the discoverer of the serpent and saurian mounds in Great Britain (which mounds agree identically with those of Ohio and Wisconsin) and who has been for a considerable time engaged in opening tumuli in Scotland for the Duke of Argyll, the Marquis of Lorne, the Marquis of Lothian, the Earl of Glasgow, and other noblemen, is at the present moment in company with an eminent civil engineer who has come with his staff from Glasgow, engaged in again visiting the Great Saurian Mound on the estate of T. W. Murray-Allan, Esq., of Glen Feochan, near this town, with the object of making cross sections of the structure and minuter details of survey than those before taken, with a view to the perfect modelling of this ancient construction, which is clearly a relic of serpent worship. We are glad to hear that when the model is complete, Mr Phené intends to present a cast to the town of Oban.—Oban Times

(I am not aware that the town of Oban has ever been presented with such an interesting cast!)

Sources, quotes and reference:

- Canmore database – chambered cairn

- Canmore database – 2nd chambered cairn and serpent mound

- ‘In the Hebrides‘ by Constance F Gordon-Cumming (1883)

- ‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’ by Dr Robert Angus Smith (1879) via National Library of Scotland

- Transactions of the Edinburgh Field Naturalists’ and Microscopical Society, Vol. VI, Part IV,1910-1911, paper by Mr Symington Grieve

- Am Baile

Photos © Jo & Colin Woolf

10 Comments

Scott K Marshall

Its a pity you dont live futher north you would save me so much research time Jo, lol

Jo Woolf

Haha, but research is fun as well!

Donald MacKinnon

Hi Jo, I’ve just read your excellent article on the Serpent Mound and the beautiful photographs. I visited it about three years ago and walked along its sinuous ridge. Standing on the cist-bearing head and looking along Serpent Mound’s back, I could see that it points directly to the distant summits of Ben Cruachan across Loch Nell. Last year, I read a fantasy adventure called ‘MacLotchim Unleashed!’ by Colin MacIntyre that included the Loch Nell Serpent Mound as part of its plot along with lots of factual information about it – such as the fact that it is aligned according to the spring equinox; its dimensions; the meanings behind the name and the folklore that goes along with it. The plot of the book (which is Book 3 of a series called, ‘On the Track of the Storm Wolves’ involving the Cailleach Bheur of Corryvreckan fame, her assistants and her storm wolves) is packed with a lot more folkore about ancient sites from all over the Highlands derived from authentic Gaelic sources. It even includes footnotes! Just a couple of other examples of localised folklore as I flick through the book: the defeat of the Great Beast of Loch Uladail by a hero called Dos on the Isle of Harris; and the battle between the Ciuthach (a giant) of Dun a’ Chiuthaich (a ruined broch that stand on a tidal island on Uig beach on the Isle of Lewis) and Fionn MacCumhail. There’s also lots of info on ancient sites of the old Celtic Church, including their associated Celtic handbells and fonts. Anyway, the guy appears to know a heck of a lot about this sort of stuff. All the best, Donald.

Jo Woolf

Wow, thank you for all this information, Donald! I hadn’t heard of Colin MacIntyre’s work. I shall have to look for that! I love how legend is tied to actual places, and when you visit them they seem so magical somehow, half in this world, and half in the other. It seems as if the books are a mine of information about history too. I must admit that I’ve been inspired to write a few stories myself, inspired by some of these legends and embroidered by imagination.

Donald MacKinnon

Many thanks for replying so quickly, Jo. Yes, it seems as if almost every mountain, hill, rock, wood, loch or ancient site once had a story associated with it, which was kept alive in the memories of the local people. Knowing the authentic local folkore deepens the significance of a place and it’s as if you seem to see through a window to a far-off time – as if past the briefly manifests itself before you in the present . Sometimes, you fel that it wouldn’t be such a shock to, say, see Fionn and his warriors careering across the landscape, hunting the deer with their hounds, or Bran and the Black Hound battling together near Dun a’ Choin Duibh. Books 1 and 2 of Colin MacIntyre’s ‘On the Track of the Storm Wolves’ series are called ‘The Cat Snatchers!’ and ‘Winter Storm Wolves Flying High’. He also wrote another book filled with Gaelic legends (which stands on its own as a single volume) called ‘Where Black Wings Rest’, which I also enjoyed. It includes as background for the plot folklore about the supernatural white stags of Ben Alder who lived through many reigns of kings; a mysterious cairn (which actually exists) on top of Creag Meagaidh (it’s called Mad Meg’s Cairn); and it also includes a once well-known Fingalian legend of King Earragan of Lochlann who set out with a fleet of forty warships led by a sacred ship of yew to do battle with Fingal and his men in Glen Coe. Best wishes, Donald.

Jo Woolf

I totally agree with what you say about local folklore and seeing a far-off time as if through a window. Sometimes I feel as if all these things are still going on! Colin MacIntyre’s books will have to go on my reading list! I love the idea of a sacred ship of yew, and the white stags of Ben Alder. Thanks so much for all this info, and for pointing the books out to me.

Richard penrose lochnell

Hi there I come from Oban Argyll as a young boy we used to fish loch nell most weekends from Friday to the Sunday sleeping in the open in summer nights it was a fantastic time of my life. We ate the nuts and the fish that we caught. We would sit around the camp fire and swear we could see and hear things out in the loch like the loudest splashing but nothing to be seen or something moving along the shore but nothing there we were teenagers with imaginations but honestly you never can tell ..I believe it’s magical..I don’t live in Oban now but I was looking at pictures of loch nell and saw your article on it and thought I would share my story.

Jo Woolf

Hi Richard, what fabulous memories and I can well believe the experiences you had. Those are the kind of things that would have been woven into legends long ago, and told to generations around the fire! There’s a magic about these places – you can feel it, as you know, but it’s impossible to explain. Thanks so much for sharing your story.

Frank Yeoman.

Curiously the map shows two cairns. Where Phene say the head of the snake is, no one seems to notice, he also finds another snake mound up at Clenamacrie, Up in Glen lonan, another more obvious esker because sheep have made scrapes in it. These cairns are all contemporary and part of the Cliegh group at the south end of Lochnell. They favoured this type of ridge, for cairn construction. On the shore it was raised beaches. I’m sure that if ophiolateria was being practiced in the early Bronze Age, we would have figured it out.

The N.L.S. Have a good bathymetric chart of Loch Nell, as well as the maps of Timothy Pont. 1583-1614 who made one of Lorn. It shows Lochnell Castle Island, at the head of the loch as some edifice.

I reckon they barged a lot of the stones ashore, and perhaps used it to build their farms. When they flitted. When you row round,what’s left in the loch is still an impressive pile of stone.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Frank! That’s very interesting. I didn’t know about the snake mound at Clenamacrie. Do you have a special interest in the archaeology of this area?