Deer carvings at Dunchraigaig

In the autumn of 2020, some extraordinary carvings of deer were discovered in an early Bronze Age burial cairn in Kilmartin Glen. They were noticed by Hamish Fenton, a visitor to Dunchraigaig cairn, who shone a torch on the underside of its immense capstone and noticed something that looked like a deer with antlers.

The discovery caused something of a sensation, and in the months that followed the interior of the burial chamber was thoroughly examined and recorded, using techniques that included a process known as structured light scanning. In all, five animals were revealed: two red deer, one of which has clear anatomical features such as antlers, legs, a long neck and a short tail, and three more animals that are less distinct but which may represent young deer. All the carvings have been ‘pecked’ into the rock using a hard implement, most likely a stone tool. It is believed that they were done before the capstone was put in place, which would certainly have made the work easier; they may even have been carved into a nearby outcrop of rock, which was later cut up to build the cist.

Dunchraigaig Cairn was first excavated in the 1860s, when three stone burial cists were discovered, containing burnt and unburnt human remains. Although no organic material has survived from this excavation, the cairn is believed to be around 4,000 to 5,000 years old. What makes the newly-discovered deer carvings so significant is that these are the first known depictions of animals of this age to be found in Scotland.

What they represent is a matter for speculation: they could be purely figurative, or they might have a deeper meaning that connected them in some way with the people buried there. Deer were an important source of food, skins and tools, and early human inhabitants of Kilmartin Glen would have been very familiar with the way their life cycle and behaviour were attuned to the seasons.

A few weeks ago, I went down to Dunchraigaig with a torch and some waterproof trousers, in order to take a closer look.

The cist is visible as a long low opening in the side of the cairn, its roof consisting of a huge flattish slab of rock resting on stone supports. Getting in there and lying down to look at the underside should have been a simple matter, but once inside I found myself thinking about the likely proximity of spiders and the weight of the rock above!

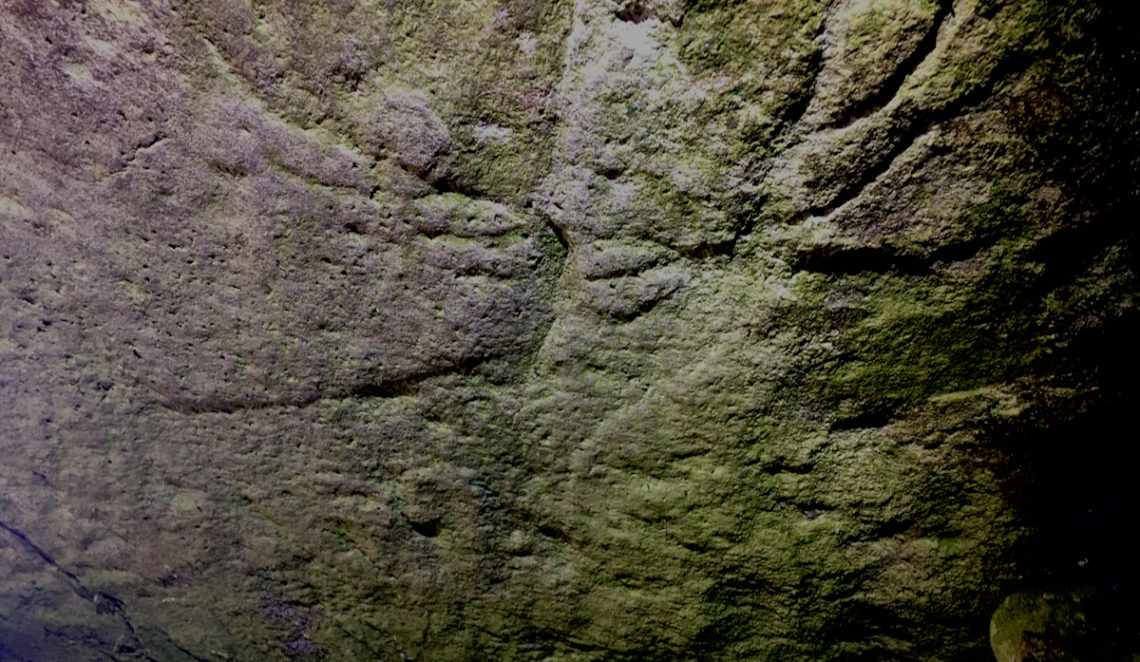

So where were the deer? After some squirming about, an astonishing spread of antlers, almost wreath-like, appeared in the torchlight. They were bigger than I’d expected, and beneath them I could make out a head and body. It’s quite extraordinary.

At very close range, it was hard to know exactly what kind of photos I was taking. I was therefore delighted that one of the deer is quite visible in the images. And what magnificent antlers! They remind me of the ‘branchy deer’ that were pursued by the warriors Gaul and Garno in the poem – reputedly ancient – about Annir and the Castle of the Red-haired Girl.

Amazingly, the second deer is also visible in the photos (I didn’t see it in the cairn itself). It’s close to a supporting boulder, but if you know what you’re looking for you can just make out a head and antlers (lower left in image above). I’m guessing that the other three animals are near impossible to see with the naked eye. All are illustrated in a diagram produced by Historic Environment Scotland (a link to their info sheet is given below).

We’ve been seeing roe deer regularly in the fields down the road – a buck, a doe and two fawns – and the other day a doe was munching away on ferns and other leaves just above the back garden. Red deer are less frequently seen but they’re still around, and from the middle of September we usually hear them roaring. It feels strange yet somehow reassuring to think that the people who carved these deer some 4,000 years ago were hearing and seeing the same things.

This isn’t the only deer carving I’ve come across – a couple of years back we walked to the ‘deer stone’ (right) by the Barbreck river in Glen Domhain. This is smaller, more difficult to find, but very intriguing. You can read more in this blog post.

This isn’t the only deer carving I’ve come across – a couple of years back we walked to the ‘deer stone’ (right) by the Barbreck river in Glen Domhain. This is smaller, more difficult to find, but very intriguing. You can read more in this blog post.

More information:

- Historic Environment Scotland info sheet (PDF) on Dunchraigaig deer carvings

- Historic Environment Scotland – news item

- Kilmartin Museum

With thanks to Tara Coggans, an archaeologist who runs heritage workshops, for telling me more about Dunchraigaig Cairn.

There’s no easy way to observe these carvings – you have to lie inside the cist and look up at the roof. It’s low, dark, and likely to be damp.

Images copyright © Jo Woolf

7 Comments

Bob Hay

Fascinating stuff Jo. Considering how much of a food source deer were to these people, maybe the carvings represented food in the next life. Doubt if we’ll ever know.

I’ve often wondered if the cup and ring art all over Europe was done by itinerant artists or carried to all areas from some original ‘school’ of thought.

I must have walked over the massive Cochno Stone five or six times without knowing it was there when I tramped the Kilpatrick Hills.

https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/will-secrets-behind-5000-year-old-cochno-stone-finally-be-solved-006607

Jo Woolf

Thanks, Bob. That’s an interesting point about the itinerant artists. I think one of the theories about those enigmatic stone balls was that they were a showpiece for a carver’s art, which is a lovely idea. I haven’t seen the Cochno Stone but from what I’ve seen online it looks magnificent. Guessing it has been covered over again now. It does make you wonder what else is beneath your feet, especially around here, and you’re just not aware of it.

Bob Hay.

They did rebury it Jo, to protect it from cretins like this.

https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/mynydd-eglwysilan-0019196

Jo Woolf

Oh my gosh, why????

Bob Hay.

He wouldn’t give a reason.

Simon Tough

social media has a lot to answer for in society!

Jo Woolf

You are so right!