From the River Awe to Loch Etive

Where to go for a walk that’s somewhere different, but not so far from home that you’ve wasted most of the precious November daylight driving there and back? This is what I was pondering the other day, knowing also that I needed to be here morning and evening so that I could go and see the delightful Tigs, who was relying on me to supply him with kitty treats (and other food, of course).

We ended up in Taynuilt, a village not far to the east of Oban. Here, in the graveyard of Muckairn Parish Church, are the ruins of a much older church, known as Kilespikeral or Killespickerill. The weather and the light were perfect for admiring old stonework, especially with the magnificent backdrop of Ben Cruachan under a fresh covering of snow.

Kilespikeral is an unusual name, and I wondered which saint might be remembered here. According to the National Records of Scotland, a church was built here in the early 13th century by Harald, the first Bishop of Argyll, and it used to be known as Cilleasbuig Earaildd (Bishop Harold’s church).

The website of the Scottish Episcopal Church sheds further light on it: ‘Until 1188, Argyll had been part of the Diocese of Dunkeld, but in the reign of William the Lion, the then Bishop, John the Scot, petitioned that Argyll, as a Gaelic speaking region should be served as a separate diocese with a Gaelic speaking Bishop. Harold, his former Chaplain, was consecrated as the first Bishop of Argyll. His Cathedral was first located in Muckairn near Oban, before it then moved to Lismore.’

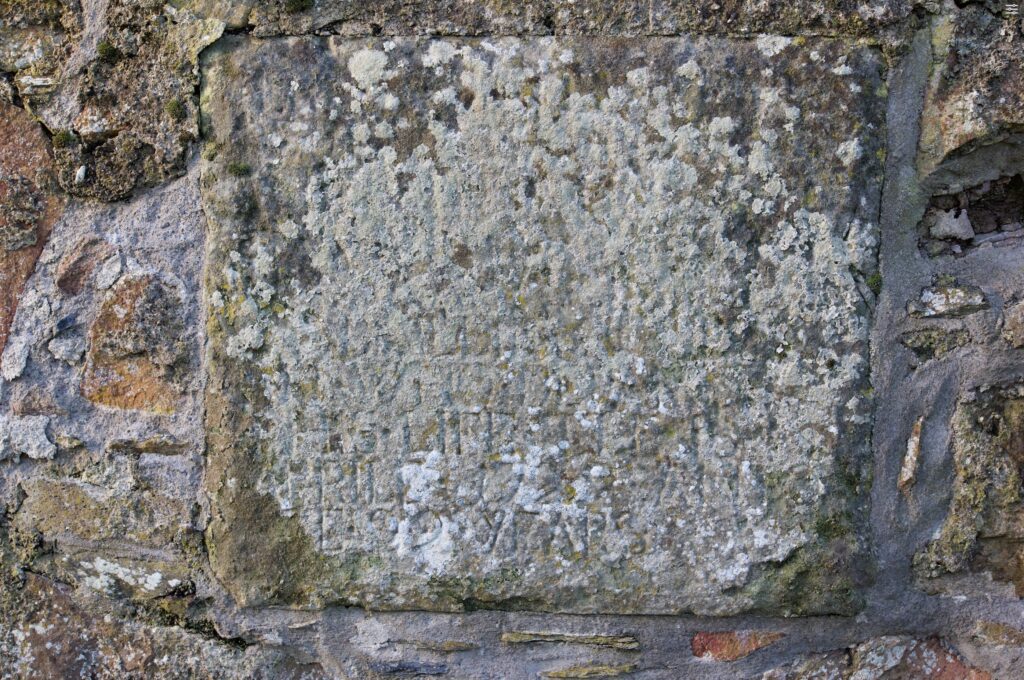

Above: old grave slab next to the church; below: a memorial stone built into the (probably partly reconstructed) wall. Sadly it’s now largely illegible, but I thought I could see ’99 years’ in the bottom line

I had no idea that a church of such importance was once here. It seems from various sources that the ruins were smothered in ivy until fairly recently, but that has now been removed. Only the east and south walls survive to any great extent; architectural notes refer to a small square aumbry in the east wall and the remains of a window embrasure and an arch in the south wall, but it’s hard to get a grasp of what the church might have looked like. Harled walls, perhaps, like the old churches further west, but was the roof made of slate or thatch?

With the recent demise of the Canmore database, it’s now difficult to find detailed and easily accessible records of historical sites, especially ones that are relatively obscure. However, I’d skimmed through an online description that said a small carving of the kind known as sheela-na-gig was built into one of the walls. We looked for it in vain, and then I realised that I’d totally misunderstood. The sheela-na-gig wasn’t on the old church at all, although that was its former home; it had been incorporated into the ‘new’ church, built in 1829, and there it was, high up in the south wall, clear as day.

This sent me on a quest to find out more about sheela-na-gigs…

These small and ancient-looking stone figures, consisting of a grotesque-looking head and body of a woman displaying her genitalia, occur in churches throughout Britain and Ireland and have perplexed historians for generations. However, they seem to be uncommon in the west of Scotland. Apart from at Taynuilt, the nearest ones to us are on Iona’s nunnery – which is apparently badly weathered – and at Kilvickeon in the south-west of Mull, which I’ve visited a long time ago without knowing it was there or taking any photos that happen to include it.

Theories about their purpose and symbolism have varied widely over time: some 19th century historians believed that they were placed in a building to ‘avert the Evil Eye’, and that ‘the enemy passing by would be disarmed of evil intent against the building on seeing it.’ Others expressed their moral indignation at the woman’s pose and nakedness, and thought the figures were designed to ‘eradicate lewdness.’ Unable to explain how such immoral womanly behaviour was illustrated in a church, some writers suggested that the carvings must have originated elsewhere.

But another theory has been put forward, that these carvings show a woman in labour. In her book, Sheela-na-Gigs: Unravelling an Enigma, Barbara Freitag places the sheela-na-gig ‘in the realm of folk deities in charge of birth.’ She continues: ‘Folk deities are found in peasant societies and they belong to the common people. I shall argue that in the folk world Sheelas were associated with life-giving powers. Their assumed main task was assistance in childbirth, but they were probably also regarded as guarantors of fertility in humans, animals and crops.’

Barbara admits that there is little evidence to back up this theory, but she suggests that these carvings represented beliefs – some would have called them superstitions – that were too widespread and deep-rooted among the population to be disregarded by the Christian church, so a compromise was reached whereby the figures were preserved and displayed until such time as they could be quietly disposed of.

Considering that these little figures might go back as far as the 12th century – according to some studies, anyway – the fact that some still survive shows just how unwilling church-goers were to abandon a symbol of a former belief, even if the basis of it might have been forgotten. Maybe no one would admit to something that amounted to paganism, but it’s easy to understand their reasoning: a walk around any old graveyard will prove just how many women died during or after childbirth, and how many of their children died in infancy.

It should be remembered that this is just one theory, and the discussions around the purpose of sheela-na-gigs are wide-ranging and complex. However, to my mind, I actually prefer these blatantly alive-looking (albeit rather distressed) figures to the macabre symbols seen on many gravestones from the 1700s that are collectively described as ‘memento mori’, consisting of skulls and crossbones.

Happy with our detective work, we moved a few hundred yards north, to Bonawe, where an 18th century iron furnace is still beautifully preserved, and then headed down a tree-lined lane towards the River Awe.

Bonawe iron furnace

I’ve often wondered exactly where the River Awe – which emerges from Loch Awe – flows out into Loch Etive, and we followed the last half mile or so of its four-mile course in order to find out. Crossing a nicely-designed footbridge, we walked alongside the river and then up and around a hydro power station before coming out onto the pebbly shore of Loch Etive. To the north-west, Ben Starav reared its snow-dusted head. A few fish-farm boats were moored, but there was no one about. Brisk little waves were lapping onto the shore, driven by the kind of nagging wind that makes your bones ache. It was impossible to linger in one place. We looped around and headed back.

There’s an old story about the origin of Loch Awe that I think I’ve mentioned before, but it’s worth revisiting because the season seems so right. The Cailleach, or hag-goddess of winter, was watching over her herd of deer on Ben Cruachan. It was her custom to guard the spring that flows from the mountain’s peak: every evening she would place a capstone over the well, and every morning she would lift it off. But one evening, as darkness fell, she was so overcome with tiredness that she forgot. That night the well overflowed, filling the glen below and creating Loch Awe. And from Loch Awe, the water gouged out a channel between the mountains, allowing the River Awe to find the sea.

During the autumn and winter months the Cailleach came into her power. She wielded a staff of blackthorn with which she struck the ground, causing it to freeze. The first snowfall of winter was seen when she washed her great white plaid in the whirlpool of the Corryvreckan, a task that traditionally took three days, and then spread it across the hills to dry. But in spring, she threw her blackthorn staff under a holly tree and yielded her power to Bride or Brìghde, who ruled over the summer months while the Cailleach slept. It has been suggested that Brìghde and the Cailleach are two aspects of the same goddess.

It’s interesting to read in Anne Ross’s The Folklore of the Scottish Highlands that Brìghde ‘was taken over into Christianity as St Brigid of Kildare,’ and that she was ‘held to be the midwife of the Virgin Mary.’ St Brigid was ‘invoked in the Highlands by women in child-bed who sought her assistance in an easy and safe delivery.’

It’s tempting to try and connect Brìghde and the Cailleach with the much-eroded little carving that still sits on a low hill in the shadow of Ben Cruachan, and indeed some historians have explored the idea that Sheela-na-gigs represent an Earth goddess in some form; however, our understanding is full of gaps and there are too many unanswered questions. But we can be pretty certain that herds of deer – beloved of the Cailleach – come down from Ben Cruachan to drink from the river. We saw plenty of their hoofprints as we walked along its banks.

And as for Loch Etive, its restless waters are fed not just by the River Awe but by burns far to the north, at the head of Glen Coe. Along its shores and on its rocky islands there are place-name memories of another story, that of Deirdre and Naoise, two doomed lovers on the run from a jealous king. Seeking sanctuary, they turned their boat into Loch Etive and lived as fugitives until deceitful kinsmen persuaded them to come home. Then Deirdre looked back at Loch Etive and sang a heartfelt lament for her lost happiness. This is one of my most-loved stories and you can find it in full in my blog post on Deirdre and the Sons of Uisneach.

The Cailleach must have been giving her plaid a thorough wash this week in the Corryvreckan. The hills are white, and there are white horses in the sea. When you need to wear two coats just to put out the bird food, you know it’s winter. But in the bed next to the porch, the green tips of snowdrop leaves have pushed up through the soil. Brìghde might be fast asleep, but the tiniest living things can hear her breathing.

–

Loch Etive features in my book, Britain’s Landmarks and Legends, available from bookshops – or you can buy a signed copy via Colin’s website.

Quotes and reference

- National Records of Scotland

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Scottish Episcopal Church, The Diocese of Argyll and the Isles

- A Corpus of Scottish Parish Churches (St Andrews University)

- Barbara Freitag, Sheela-na-Gigs: Unravelling an Enigma (2004)

- Anne Ross, The Folklore of the Scottish Highlands (1976)

- The Sheela-na-Gig Project offers an alternative interpretation of the Taynuilt carving

Photos copyright © Colin and Jo Woolf

More posts about Loch Etive

- Ossian, Fingal and the Falls of Lora

- Ardchattan Priory

- Ardchattan: in the footsteps of St Baodan

- Looking for the yew of Easragan

12 Comments

Finola Finlay

Lovely post, Jo! The Cailleach. In all her manifestations, was the subject of the latest Into the Mythic podcast. I’m going with the evil eye explanation for the sheela-na-gigs.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Finola! I’m going to check out that podcast episode about the Cailleach right now. Thanks for your take on sheela-na-gigs. I’m guessing that you’ll have seen a good number of them in Ireland as well.

Andy Sweet

I share your winter dilemma of trying to keep drives under an hour to maximise walking time in the light.

There’s a good sheela-na-gig at Rodel on Harris.

https://www.trove.scot/place/200713

Jo Woolf

Thank you for this, Andy. The one on Harris looks much better preserved than most. Looking at the map again for possible walks this weekend – guess we just have to be creative!

freespiral2016

I’m with Finola! Interesting how your adventure seemed to come together with the Cailleach, Sile and Brighde all present. Siles are so fascinating!

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Amanda. That was total serendipity, how the elements came together. I was just looking at your own blog for the sheelas or siles that you’ve come across yourself. I was only vaguely aware of these features before I came across this one at Taynuilt.

Bob Hay

Very interesting report Jo, especially re the ironworks. They made cannonballs for the Napoleonic Wars there (probably to go with naval carronades from Carron Ironworks in Falkirk).

This may sound sacrilegious and may the Good Lord forgive me, but I read somewhere that the English owner of the foundry inniated / invented the kilt for keeping his workers legs dry while trudging through the heather to get to work 😂

Jo Woolf

Thank you, Bob! The ironworks are very well preserved. I believe that a lot of the charcoal came from Taynish woods, where the mounds of the old charcoal burners can still be seen. Crikey, I can’t see kiltmakers rushing to put that story on their websites any time soon! 😂

Bob Hay.

Hoots toots lassie ah cannae help but agree wi’ ye.

Quite an exercise getting the ore up from Cumbria to Lorne.

https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/bonawe-historic-iron-furnace/history/

Jo Woolf

😂 😂 I’m amazed at the industry of it all, and how many people were employed there. It must have looked very different at that time. I was also wondering when the ferry stopped operating, and it seems to have stopped for good in 1966. http://ardchattan.wikidot.com/bonawe-ferry

Richard Miles

Dear Jo,Sorry for my late response.Some years ago we lived on the border of Hereford and Monmouth not far from Kilpeck church.It’s a Romanesque designed church famous for the multitude of carvings,mainly around the eaves and especially the dorrway.There is a Sheelah-Na-Gig high up on the outside.The church booklet suggests the following:-An earth mother goddess.A Celtic goddess of creation and destruction.An obscene hag,a sexual stimulant,a medieval Schandbild to castigate the sins of the flesh.There are more as you know. It’s strange that she is not shown with breasts which I would think was a symbol of fertility.Kilpeck church is worth researching ,it’s quite unique.

Richard Miles

Jo Woolf

Thank you Richard, and no need to apologise at all. It’s good to hear your thoughts at any time. I’ve heard of Kilpeck Church and I’m very interested to read the description of the sheela-na-gig. It’s striking how different the interpretations are – from an earth goddess to a symbol of lewd behaviour. I had a look just now at the church’s website, which includes some good photos. https://kilpeckchurch.org.uk/the-church/a-tour-of-kilpech-church/ What a gorgeous little place, and still so beautifully preserved. If we lived closer I’d love to go and see it! Thank you for telling me about this. Best wishes, Jo