Alexander II and the ‘ghosts’ of his galleys

Looking roughly north-westwards from our house, we can see the islands of Shuna, Luing and the south-eastern end of Mull, with Ben More and the lower hills rising beyond; we can also see the small, low island of Torsa. With binoculars, you can make out a rocky knoll at the north-east tip of it, partly covered in vegetation. It’s barely recognisable now as a man-made structure, but apparently a castle stood here in medieval times; and it may well have been the place where a Scottish king spent the last night of his life.

The site of the old castle on Torsa, highlighted by the sun. Directly behind it (on the Isle of Seil) is St Brandon’s chapel and Ballachuan hazel wood

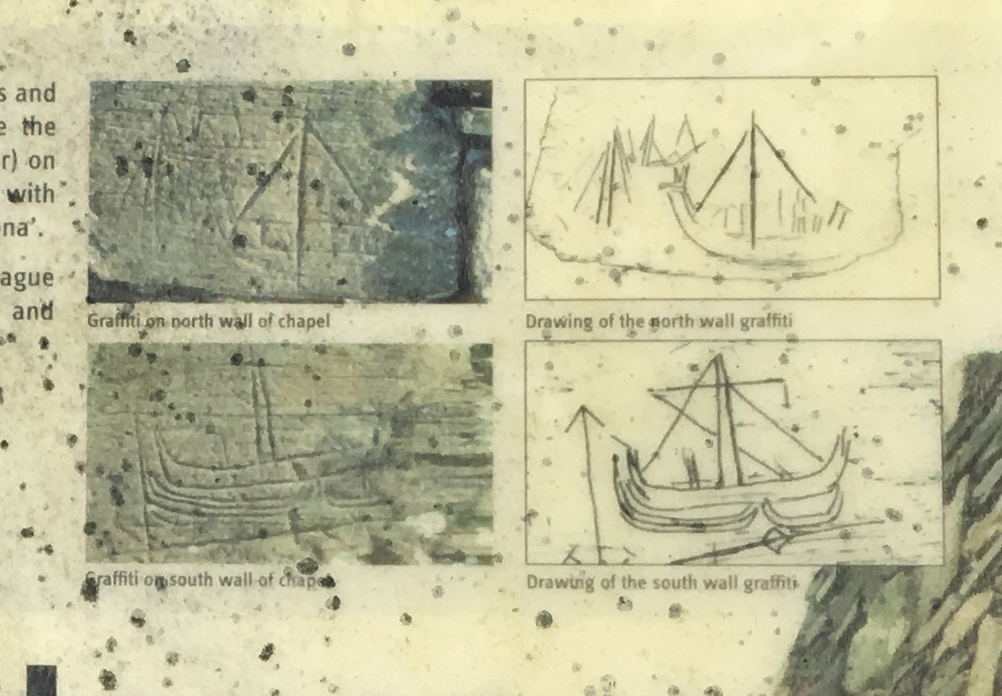

Quite often, I gaze out of the window and imagine what the sea must have looked like with a fleet of galleys in full sail, heading up the Sound. It might not have struck observers at the time with admiration and awe – more likely apprehension or dread – but it must have been a magnificent spectacle all the same. In view of the violence that often followed such an appearance, it’s understandable that the local people rarely stayed on the scene to make sketches… but according to some historians, on one memorable occasion in the 13th century that’s precisely what they did, and their impressions are still visible on the walls of a ruined chapel on the Isle of Luing.

The story is set in the summer of 1249. By this time, Alexander II had ruled over Scotland for nearly 35 years. He was ambitious and strong-minded, brutally suppressing rebellions in Caithness and Galloway and forging the Treaty of York with Henry III of England, an agreement which defined the English-Scottish boundary in a line running from the Solway Firth to the Tweed. But in the west of Scotland he was still having problems with the rulers of the Isles – those descendants of Somerled who stubbornly clung on to their allegiance with the Norse kings. He mustered a fleet of ships and set out on a mission to bring them to heel.

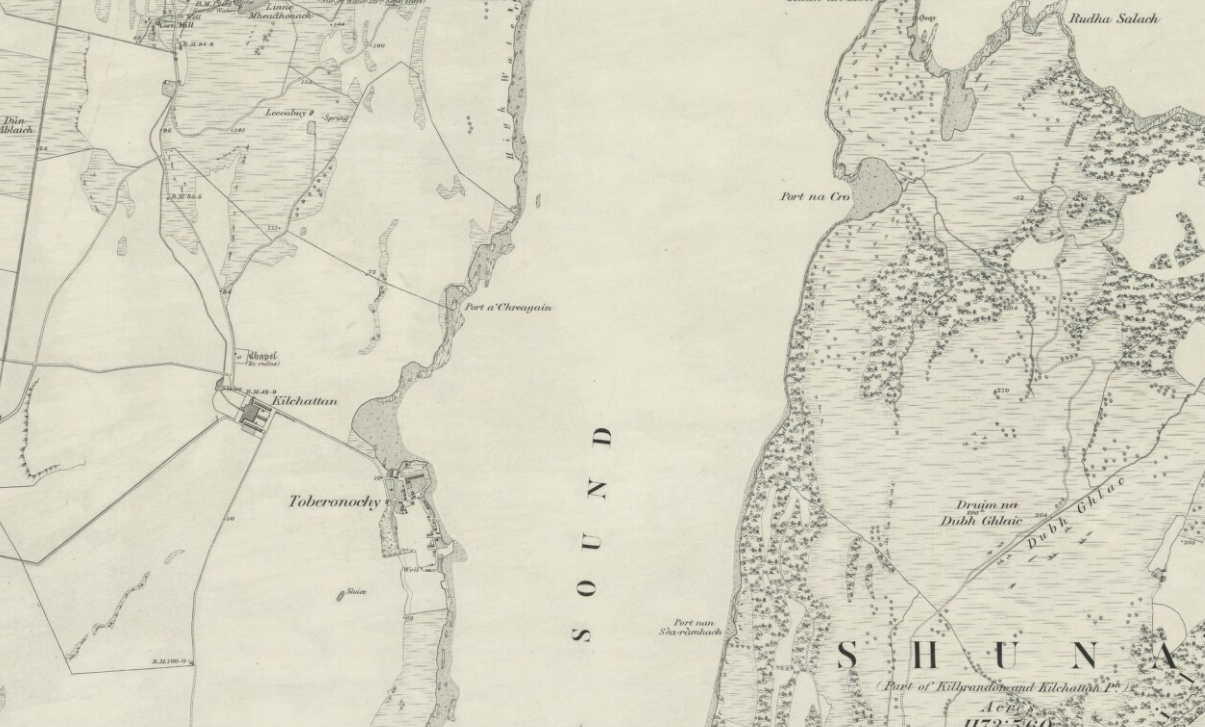

It is most likely that Alexander’s fleet set out from the Firth of Clyde, but instead of sailing around the Mull of Kintyre, the historian Marion Campbell suggests that they took a short cut overland by way of Tarbert where “most of the ships were dragged over the isthmus along what was almost certainly a permanent timber ‘shiproad.’” After staying in Tarbert Castle, Alexander may have ridden directly across to join them in West Loch Tarbert, or he may have taken a longer route, by way of Dunardry or Dunadd to the north, visiting strongholds and being entertained by loyal subjects on the way. On 7th July the fleet would most likely have been anchored off the east coast of Luing.

One of Alexander’s intentions was to meet with Eóghan MacDubhghaill (Ewen MacDougall), one of the powerful rulers whose loyalties were causing him so much annoyance. A great-grandson of Somerled of the Isles, Eóghan was in the unenviable position of holding mainland territories under the King of Scots and island territories under King Hákon of Norway. To say he had a foot in both camps doesn’t begin to cover it. But Marion Campbell believes that the meeting never took place: Eóghan may have received advance warning of the King’s approach, but he had also learned of trouble in the Isle of Man, and had departed swiftly to deal with it. No doubt disappointed, Alexander may have spent the night of 7th July on Torsa, in a castle possibly belonging to Eóghan himself, before setting sail again early next morning, travelling north through the fast-running currents of Cuan Sound.

OS map (6″, 1st ed., 1880 Argyll) showing Torsa (‘Torsay’) and part of Luing, with the castle marked as ‘fort’ close to the top edge. The fleet may have anchored in Ardinamar Bay.

Ultimately, Alexander may have been heading for the Western Isles in an attempt to provoke King Hákon into a showdown. Some historians believe that this was his intention all along. We shall never know for sure, because when the fleet reached Oban Bay, disaster struck. On 8th July the King was taken ashore on the island of Kerrera, where he died suddenly, of a brief and mysterious illness. For his horror-stricken supporters there was now nothing to be done but to bear his body home with speed and dignity, and to arrange for the coronation of his seven-year-old son.

Above and below: Kilchattan chapel, Isle of Luing

So where does this leave us in terms of that enigmatic local ‘sketch’? Let’s rewind history back a day, to 7th July when the galleys were anchored off Luing. They must have been a breathtaking sight to behold:

‘Presumably the ships resembled Norse longships, of shallow draught, with one large square sail and with oars, highly manoeuvrable and able to beach on any sandy shore.’ (Marion Campbell, ‘The Kist’ no.22, 1981)

Carved into the outside walls of the little chapel of Kilchattan on Luing, on both the north and the south side, are some shapes and symbols that appear to represent a fleet of ships very similar in shape and construction to those that appeared in the summer of 1249. The lines are vague in places, but you can still make out their sleek profiles and tall masts. One has a gangplank lowered, and another is thought to bear a figurehead of a wolf or a dog. By comparing these with contemporary carvings from Norway, Miss Campbell and other historians have speculated that these images may indeed depict Alexander’s fleet in the waters off Luing. Miss Campbell even detected what she thought were triangular ‘flags’ attached to bow and stern; these were often made of gilded bronze, and acted as weather vanes for the helmsmen. She says that the Sagas speak of them ‘waving like flames’ over a fleet.

This stone (below) is incorporated in the north wall (above)

Below: carvings on the south wall

Above: Drawings of two of the carvings from the chapel’s information board. More detailed drawings can be found in Marion Campbell’s article in The Kist.

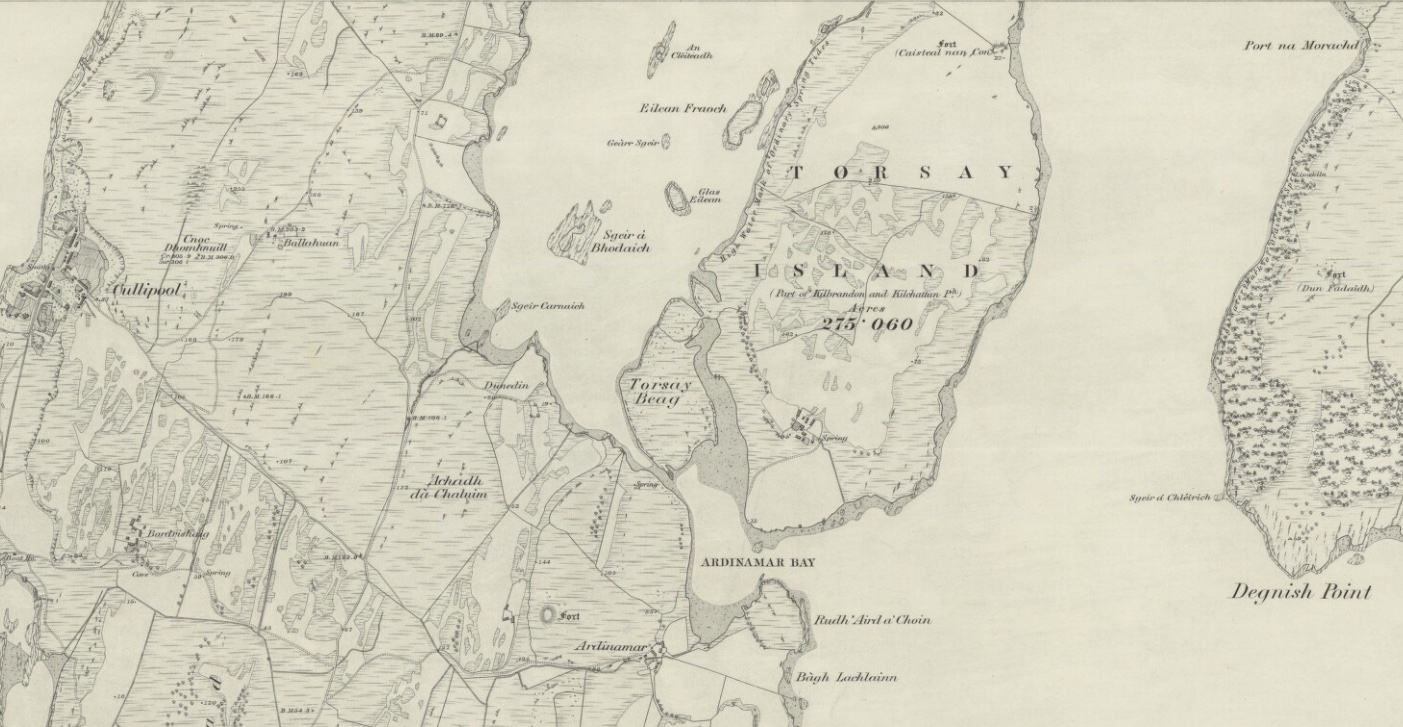

Part of OS map (6″, 1st ed., 1880, Argyll) showing Kilchattan Chapel on Luing. This is just south of Torsa and would have offered a great view of the Sound of Shuna

Part of OS map (6″, 1st ed., 1880, Argyll) showing Kilchattan Chapel on Luing. This is just south of Torsa and would have offered a great view of the Sound of Shuna

Now, believing that these carvings depict Alexander’s ships, and are contemporary with his visit, does require a leap of faith (or imagination). For a start, there is no real way of dating them, other than from the type of ships they portray, and from the obvious fact that they have been weathered by time. According to Canmore, Kilchattan chapel (‘the church of St Cattán or Cathan’) is ‘probably 12th century’, so it would have been standing by 1249. But a couple of unwanted questions pop into my head: firstly, I wonder just how acceptable it would have been in the 13th century, to set about carving secular images into the wall of a church. What would the Bishop have had to say about it? And why are there carvings on both the north and the south walls of the chapel? Were they done by more than one person, or at different times? I even wondered if the stones could have been carved previously in a different location (or on an earlier chapel – ‘Kilchattan’ suggests the presence of an early missionary-saint) and then incorporated into the existing 12th century structure. Also, were the walls of these old chapels not originally whitewashed or ‘harled’? Would that have made it more difficult, or more tempting, to set about them with a sharp blade?

I know it’s frustrating, but I doubt we’ll ever know. If you can allow your mind to make that leap, though, you might snatch a glimpse of something extraordinary even in that time of frequent seaborne dramas. These vessels symbolised the pride and power of a king whose golden age was about to come to an abrupt end. Theoretically, at least, he had come in peace, so there might have been more reason to commemorate his visit rather than snatching up arms or taking to the hills. And if the carvings don’t represent that particular event, that means they must surely recall something else – something equally significant for the inhabitants of Luing and Argyll as a whole, and equally tantalising for us.

The fine weather has turned now, and the islands are receding into a soft grey drizzle. Is it on such days that the ghosts of these galleys return?

Footnotes:

Before he died, Alexander gave the ‘church of St Bride in Lorn’ to the bishopric of Argyll. This is Kilbride, a lovely little place on the north shore of Loch Feochan, which we visited several summers ago.

The MacDougalls held a string of castles around the coast of Argyll. Examples include Dunollie, Dunstaffnage, Duntrune, and Coeffin on the Isle of Lismore. Eóghan’s father, Duncan, founded Ardchattan Priory on Loch Etive. This was a traditional burial place of MacDougall chiefs until the 1700s, and is the home of the splendid MacDougall Cross.

On old maps, the castle on Torsa is called Caisteal nan Con – the ‘castle of the dogs’. A dun here on the Craignish peninsula has a similar name: Caisteal nan Coin Duibh (‘the castle of the black dogs’). A linked legend, perhaps… or maybe these old warriors loved their hounds!

References and further reading:

- ‘The Western Voyage of Alexander II’ by Miss Marion Campbell, from The Kist (the magazine of the Natural History and Antiquarian Society of Mid Argyll), no.22, 1981

- History Today: ‘The Death of Alexander II of Scots’ by Richard Cavendish

- ‘Somerled and the Emergence of Gaelic Scotland’ by John Marsden

- Canmore: Kilchattan chapel

- Canmore: Caisteal nan Con, Torsa

- Isle of Luing website

- Saints in Scottish Place-names

- Maps: Argyll, 6″ 1st ed., 1880, courtesy of National Library of Scotland

14 Comments

Ashley

A wonderful, fascinating story in a beautiful setting! Of course that is, seen from the 21st century! A great post, many thanks.

Jo Woolf

Thanks, Ashley! It would be so interesting to know what local people made of it – whether the children all gathered down on the shore to have a look! I often wonder what sights this part of the coast has seen over the centuries.

Ashley

So true, our coasts in particular have seen so many ‘comings and goings’.

davidoakesimages

Enjoyed that read (as always). Just wish I had been aware of the stone markings in the Chapel. I posted a simpler tourist type blog back in June. It was the graves and the Slate miners story that made the impression on me. The link is here :- https://davidoakes-images.com/2020/06/28/silent-sunday-so-off-to-church-40/

Jo Woolf

Thank you, David! Loved your post and the pics are fabulous. There are lots of stories attached to that little chapel! I haven’t investigated the others properly yet, but they do sound interesting!

davidoakesimages

I guess that another project to add to your list ?

Keith Miller

Very interesting article and beautifully produced – many thanks. Hope I can manage back to the old church graveyard by Toberonochy for a wander and a closer look. And across to Torsa too – is the gap tidal or is a dinghy needed?

Jo Woolf

Thank you very much, Keith! I hope you can get back there too. A friend on Luing says you’d need a boat/dinghy to get to Torsa. Perhaps let us know if you’re up and we might be able to help (might even join you, haha!)

Keith Miller

Thanks Jo – I may do that…but I still occasionally take duties as a relief boatman on a fast scallop diving RIB out of Oban and we often swing through Cuan Sound and round Torsa. So I might be able to step ashore if circumstance are favourable. Many thanks….

Jo Woolf

Wow, sounds fab! Hope you get there one way or another.

Bob Hay

Hi Jo. I posted some comments on the above article last week but they seem to have dispappeared into the ether. For any of your readers really interested I mentioned Denis Rixon’s definitive book ‘The West Highland Galley’ a fascinating history of these remarkable craft.

Anything about these West Highland castles is of great interest. Some of them undoubtably rose from the ruins of Iron Age forts artefacts from which have been found in the waters around Castle Tioram for example and the fact they embodied current building technology from the mainland makes one wonder who the actual stonemasons were and where did they come from.

All intriguing stuff.

Jo Woolf

Hi Bob, don’t worry, I did get your comment – it appeared on the post ‘Caisteal nan Coin Dubh’ – you must have followed a link to the Castle of the Dogs, close to us here in Craignish! I must look for Denis Rixson’s book. Yes, there are more of these ancient forts than I realised – there’s one above us on the hill, and close by on an island near Craobh. The technology of the builders is a very interesting question!

Bob Hay.

First thing i’d buy if I went to live in Argyll would be a good metal detector and I’d be out on those hills every day.

We stayed in a B+B on the hillside above Eilean Donan one time and the owner showed me the remains of a sword he’d found in a ruined cottage up around there and a cannon ball from the time the Royal Navy bombarded the castle as there are a lot buried in the hillside.

As I caught him on film showing us it, he said, ‘And if there are any English folk watching this, the answer is, no, you’re not getting your ball back’.

First time there I’d ever seen live pine martens which he fed on his handrail every night.

Jo Woolf

I’ve often thought that myself – there must be lots of hidden ‘treasure’ and artefacts lying around beneath the surface. And on the sea bed! Amazing to hear about the sword and cannon ball. We occasionally see pine martens here too, they are very bold!