Deirdre and the Sons of Uisneach

I’ve found so often that the places around here, on the coast of Argyll, are infused with the legends of Ireland; it doesn’t seem so unlikely when you consider that, a thousand or more years ago, the intervening seas were easily navigated by fast and nimble ships, and there was a long migration of people, cultures and ideas between the two shores. There are many examples of Irish legends that have taken root in Argyll, including Diarmaid and Grainne in Glen Lonan, and the dog-fight between Bran and Foir in Craignish, which I wrote about just recently.

Another legend, which I’ve been wanting to explore for a while, is the tale of Deirdre and the Sons of Uisneach. (I believe a rough pronunciation of Uisneach is ‘oosh-nah’). Uisneach is the name of an ancient ceremonial site, a seat of high kings that is said to lie at the very centre of all Ireland. Part of the story takes place in Scotland, and is centred on Loch Etive, where a hill fort is still known variously as Dun Uisnach, Dun Mac Uisneachan, Dun Mac Sniochan… and Beregonium. (Where does ‘Beregonium’ come from? I’ll try and return to that question, if it’s possible to answer it!)

But the most important thing is the legend itself, and it goes like this…

Conchobar mac Nessa, King of Ulster, was holding a great feast at his hall in Emain Macha (modern-day Armagh). The king and his warriors were being entertained by the royal bard, Feidhlimidh (pronounced ‘Felim’) Mac Dall. Feidhlimidh’s wife, who was pregnant, was waiting on the company, and as a favour Feidhlimidh asked whether the King’s druid, Cathbadh, would foretell the child’s future.

Cathbadh placed his hands on the woman’s belly. He said: “You are carrying a daughter, and she will grow up to be the most beautiful woman Ireland has ever seen, with clear green eyes, red lips and wavy golden hair. Her name will be Deirdre. She will be pure and beautiful, but she will bring trouble to all those who love her, and she will cause slaughter among the warriors of Ulster.”

It didn’t seem to cross anyone’s mind to ask whether Feidhlimidh and his wife wanted to call their daughter something else. They were more concerned about the doom-laden prophecy, and how they could avoid its consequences. The feast was still going on when the child was born (feasting went on for a long time in those days!) and because of the awful prediction the warriors of Ulster wanted to kill her straight away, but Conchobar thought of a more merciful alternative.

He said: “I will take this child away and have her raised in secret. When she is old enough I shall marry her myself, and then no other man will dare to look at her.” Conchobar found a nurse for Deirdre and sent them both to live with a couple who had a smallholding deep in the woods.

Exactly as the druid had foretold, Deirdre grew into a stunningly beautiful young woman with green eyes and long fair hair. One day amid the snows of winter, her foster-father killed a calf outside, and when he had cut up the meat, a raven flew down to pick at the carcass. The blood had soaked into the snow, and Deirdre watched in fascination. “My true love,” she said, “will be a man with these colours: skin as white as a snowflake, cheeks flushed the colour of blood, and hair like a raven’s wing.”

Deirdre’s old nurse, who should perhaps have known better, overheard this daydream and told her: “I know of just such a man. His name is Naoise Mac Uisneach, and he is one of the warriors of Conchobar Mac Nessa.” Deirdre immediately wanted to see Naoise for herself, and roamed around the woods in the hope of meeting him out hunting.

It wasn’t long before Deirdre spied Naoise, who was riding with his two brothers, Aindle and Ardan. Seeing that he was exactly the man she had dreamed of, she fell in love with him at first sight, and boldly stepped across his path. Seduction was Deirdre’s aim, but Naoise was having none of it. He was spellbound by her beauty, but he knew who she must be, and politely refused to run away with her as she suggested.

But Deirdre had a secret weapon up her sleeve: she put a geas on Naoise, so he had to change his mind. In the old legends, a geas is a type of moral bond which the recipient has no choice but to honour, or else face a lifetime of shame. Now, Naoise no longer listened to his own conscience or to his brothers’ warnings. He took Deirdre’s hand and they fled, accompanied by Aindle and Ardan and their followers and hounds, right across Ireland to Rathlin and then across the sea where they found safe harbour in Loch Etive.

Woods by Loch Etive

For a while Deirdre and the Sons of Uisneach lived by raiding and scavaging, but soon the King of Alba heard about their presence and invited the three young men to join his own warriors. However, he had also heard a rumour about Deirdre’s beauty, and sent a spy to see whether it was true. On hearing that it was, the King of Alba demanded that Deirdre leave Naoise and become his queen instead, but she refused, and soon the brothers and Deirdre were fleeing for their lives again, moving from place to place but never staying there for long.

Somehow, the news of their plight filtered back to Ireland, and Fergus Mac Roich, one of Conchobar’s faithful warriors, tried to persuade the king to intervene. Why should three of Ireland’s most gallant men live in misery and exile, he asked. Conchobar, who had secretly never forgotten the disloyalty of Naoise, Aindle and Ardan, saw an opportunity for revenge. Composing a deceitful message that spoke of forgiveness and reconciliation, he sent Fergus and his two sons to go and fetch them.

When Fergus landed on the shore of Alba, he gave a great shout which was heard by Deirdre and Naoise as they sat playing chess in their hidden lair. Naoise instinctively leapt to his feet. “That’s the shout of an Irish man!” he exclaimed. “Of course it isn’t,” said Deirdre soothingly. “Come, and return to the game!” But soon there was a second shout, and Naoise jumped up again. “That’s the voice of an Ulster man!” he said. “Don’t be ridiculous,” said Deirdre, and Fergus grudgingly sat back down. At the third shout, Naoise would not be constrained. “That’s the voice of Fergus Mac Roich!” he said, and went out to find him.

Deirdre was distraught. The previous night, she had had a dream in which she saw a raven that had flown all the way from Ireland with three drops of honey in its beak. When it landed, the drops fell and turned to blood. She knew that Fergus would persuade Naoise and his brothers to return to Ireland, and she knew that she was powerless to stop them. When they boarded Fergus’s ship and set sail for their homeland, she joined them with a heavy heart, and wept bitterly as she watched the coast of Alba fading into the distance. Deirdre, who was forever after known as Deirdre of the Sorrows, sang a beautiful lament for the mountains and glens and woods where she had known true love.

Glen Etive, O Glen Etive,

There I raised my earliest house,

Beautiful its woods on rising,

When the sun fell on Glen Etive.

Glendaruadh, O Glendaruadh,

I love each man of its inheritance,

Sweet the noise of the cuckoo on bended bough

On the hill above Glendaruadh.

Glenmasan, O Glenmasan,

High its herbs, fair its boughs,

Solitary was the place of our repose,

On grassy Invermasan.

R Angus Smith, quoting translated extracts from Deirdre’s lament

Glen Etive

In Ireland, as the party made their way towards the royal court, King Conchobar was curious to know in advance whether Deirdre had retained her beauty. He sent a servant to their lodgings to find out; but when the servant peered through a window, he was seen by Naoise who threw a chess-piece and knocked out one of his eyes. Despite this injury, the servant returned to the king and reported: “There is not in the world a woman of face and form more beautiful than she.”

The brothers now knew that they had been betrayed, and Conchobar was desperate to get rid of them. The druid Cathbadh conjured a great sea-tide that completely surrounded them, and through which they had to swim, even though they were on dry land. Naoise carried Deirdre on his shoulders, high above the waves, and they swam until they were overcome by exhaustion. Then Conchobar urged his warriors to kill them, but no one stepped forward, except a man called Maigne Rough-Hand, son of the King of Norway, whose father and two brothers had been killed by Naoise in a battle long ago.

Maigne Rough-Hand announced himself willing to execute each brother in turn. Aindle and Ardal both begged to be killed first, but Naoise handed over his own sword which came from the ancient sea-god Manannan Mac Lir, and would cut down anything in front of it. Wielding this sword, Maigne felled all three of the Sons of Uisneach with one blow.

Deirdre was taken, grief-stricken, to the court of Conchobar where he showered her with gifts. But she flung them away and refused to look at him. Conchobar was enraged by her rejection, and asked her if she hated any man more than he. “Maigne Rough-Hand,” was her reply, “because he killed my Naoise.” So Conchobar sent for Maigne Rough-Hand and brought him to Deirdre, saying that she could go and live with him for a year. He forced Deirdre into Maigne’s chariot, with himself on one side and Maigne on the other, joking that she was now like a ewe cornered by two rams. In desperation, Deirdre threw herself out of the chariot and dashed herself against a rock, her lifeless body landing close to where Naoise was buried.

The death of Deirdre and the slaughter of the Sons of Uisneach precipitated a war against the King of Ulster, led by Fergus, the well-meaning messenger who had brought them home. The son and grandson of Conchobar were among those killed, and many warriors left Ulster to seek the protection of the King of Connacht. The druid’s prediction had been fulfilled.

There are many variants of this story. One states that Deirdre was a daughter of a Pictish king, growing up in close friendship with the three Sons of Uisneach, and when she was taken to Ireland to marry Conchobar she insisted that they came with her. Another claims that Naoise was murdered by Eogan mac Durthacht, King of Fernmag (Farney). Yet another says that when Naoise was killed, Deirdre died of a broken heart. Legends are endlessly fluid, and they are not just things of the past – they are still evolving, and being interpreted in new ways.

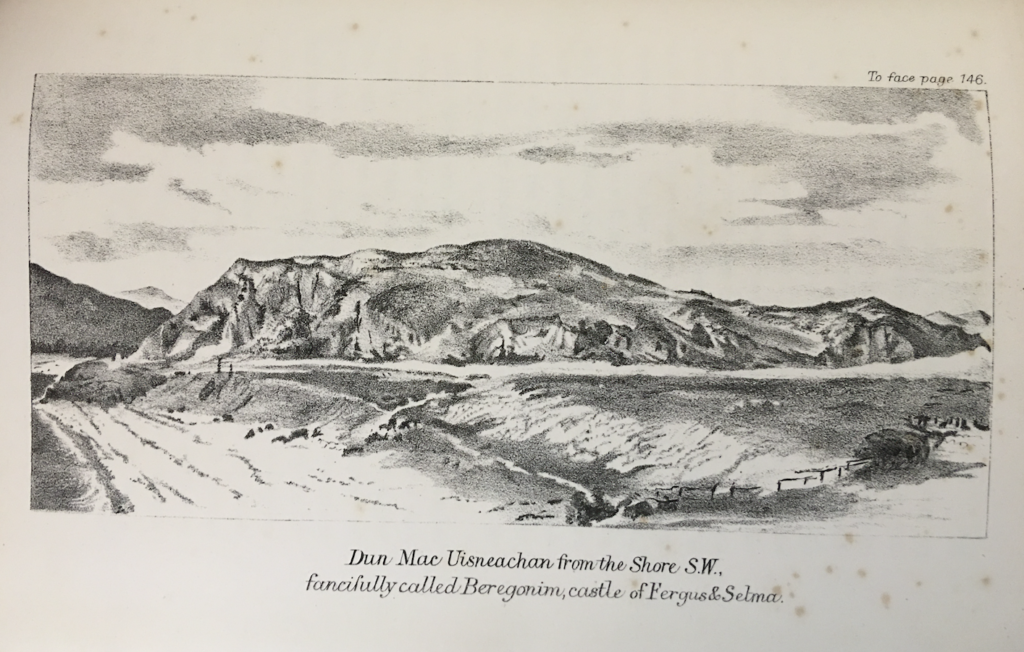

Whether or not they really existed, Deirdre and the Sons of Uisneach seem to have left many traces of their presence in the landscape. In his book, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1885), the antiquary R Angus Smith and his friends go on a leisurely and learned wander around the ancient sites of Argyll, remarking on place-names connected with the legend. Smith points to Eilean Uisneachan, an island (really a small peninsula) on Loch Etive; a rock half-way up Glen Etive that was once called ‘Deirdre’s drawing room’ (apparently a very ancient joke); and a wood near Taynuilt called Coille Naoise, or Naoise’s wood. But the focal point of his investigations is the hill fort which stands above Ardmucknish Bay near Benderloch, just north of the mouth of Loch Etive, called Dun Mac Uisneachan or the fort of the Sons of Uisneach.

The hill of Dun Mac Uisneachan, seen from the slopes of Ben Lora

Drawing of Dun Mac Uisneachan by Miss J Knox Smith, from R Angus Smith’s ‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’

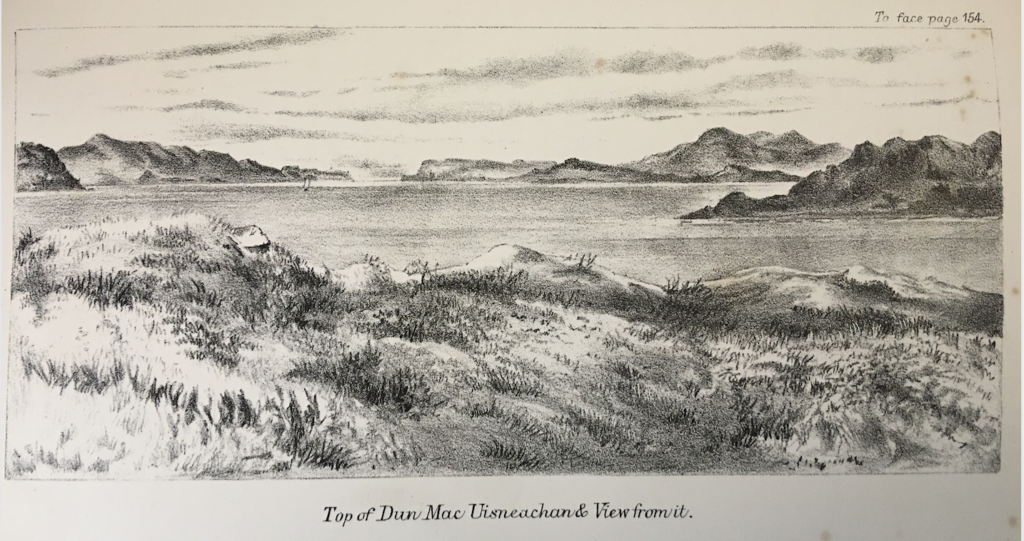

The location of the fort is first mentioned in the 12th century Book of Leinster, which describes it as being by Loch Etive, and folklore has long associated it with this particular hill. So, although Deirdre and Naoise moved around to evade capture, we can perhaps imagine them spending time here, enjoying their freedom and the splendour of the landscape in which they lived.

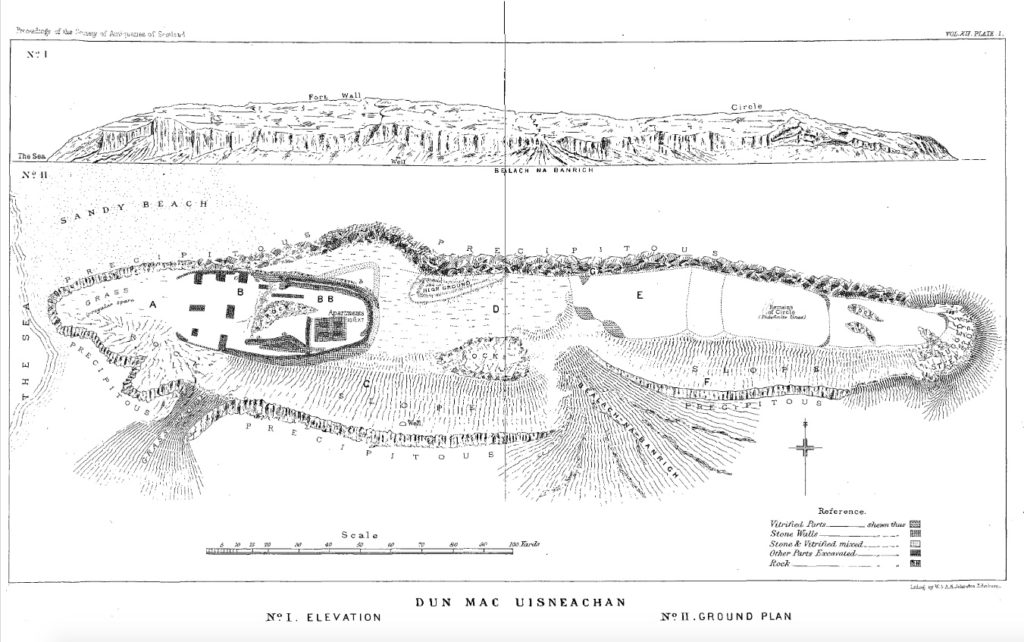

On some old maps, the fort is labelled ‘Beregonium’. The origin of this name has been debated by historians; one theory claims that it was a misprint of ‘Rerigonium’ (meaning something like ‘the place of the king’), which appeared in a work by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. It became ‘Beregonium’ in a 15th century reprint of his work, and this spelling was copied by the historian Hector Boece in the 16th century. Boece claimed that Beregonium was founded by Fergus, the first King of Scots, who brought an ancient royal chair from Ireland, on which he was crowned. This Fergus may have been Fergus Mor mac Erc, one of the founders of Dalriada… but it’s another impossible case of history, folklore and imagination being poured into a mixer and blended on ‘high’.

Segment of John Ainslie’s map of Scotland, 1789, showing ‘Ruins of the City and Castle of Beregonium, formerly the Chief City of Scotland’ (map courtesy National Library of Scotland)

“There are many stories about it. It has been called the beginning of the kingdom of Scotland, the palace of a long race of kings; also the Halls of Selma, in which Fingal lived; the stately capital of of a Queen Hynde, having towers and halls and much civilization, with a Christianity before Ireland; whilst it has also been considered to be that which the native name implies, simply the fort of the sons of Uisnach, who came from Ireland, and whose names are found all over the district, and who in the legend are reported to have come to a wild part of Alban.” (R Angus Smith, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach, 1885)

Later writers added extra layers of legend, which blur the edges still further. In his epic poem Queen Hynde (1824), James Hogg describes Beregonium as a glorious city with seven towers, the home of the first Queen of Scots in Dalriada. The city is destroyed in a fire sent from heaven: ‘Walls, towers, and sinners, in one sweep, / solder’d to a formless heap.’

The archaeology of Beregonium leaves lots of questions unanswered. Historic Environment Scotland describes the site as being ‘an impressive group of prehistoric defensive remains comprising two successive forts and a dun, dating to the Iron Age (between 500 BC and AD 500) and later.’ Vitrified material was found in the remains of both forts (this is the process whereby stones were melted and fused by intense heat, the source of which is still something of a puzzle to archaeologists. It would make a perfect explanation for Hogg’s vengeful fire!)

View from the summit, drawn by Miss J Knox Smith, from R Angus Smith’s ‘Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach’

R Angus Smith’s plan and elevation of Beregonium, included in his paper ‘Descriptive List of Antiquities near Loch Etive’, published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. He believed he had found a stone circle to the east, but I think historians now consider it to be a dun.

In papers read to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in the 1870s, R Angus Smith reported finding remnants of a vitrified wall (he was probably the first to identify them here) and a piece of a sword which came out of the stonework. He dug down and found the remains of burnt bones, which he believed were from cattle and horses. Canmore notes that the National Museum holds ‘a tanged iron sword, an iron dagger, and an enamelled bronze circular mount’, which were discovered by Smith’s excavations in 1873 and 1874.

There’s sufficient evidence to show that, at some stage in its history, Beregonium was a place of some significance. What happened there is a matter entirely for conjecture. I feel I don’t really need to know, because I love the legend.

A bit about Loch Etive

Loch Etive (in Gaelic, Loch Eite) begins its life at the bottom end of Glen Etive, a deep and picturesque valley that makes an almost right-angled turn southwards from Rannoch Moor, just before the head of Glen Coe. Fed by the River Etive, the loch runs south-west in a ragged ribbon for about 12 miles and then swerves abruptly between Bonawe and Taynuilt to head west, widening and deepening for the final stretch before surging through a bottle-neck of land at Connel. Here, the huge volume of water emptying into the Firth of Lorn is squeezed over a submerged lip of rock, and the flowing tide causes a dramatic stretch of white-water rapids known as the Falls of Lora. Interesting sites on Loch Etive include Ardchattan Priory, whose history sent me on a quest for the Yew of Easragan.

My photos show the hill of Dun Mac Uisneachan from a distance (they were taken on a walk up nearby Ben Lora). We didn’t climb up to the hill fort itself for two reasons: one, it seemed a private place with houses close by, and we couldn’t see a way to get up there without going through a garden; and two, even in early spring the summit and its steep slopes were entirely overgrown with deep vegetation, and we realised that we’d see nothing on the ground.

Further reading and reference:

- Historic Environment Scotland

- Canmore

- Ardchattan Parish Archive is a great resource, with pages on: Beregonium and Naoise and Deirdre and Dun Mac Sniachan

- R Angus Smith, Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach (1885)

- R Angus Smith, papers published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

- Marcus Pitcaithly has written a brilliant and in-depth blog post about Beregonium, Scotland’s Lost Capital

- Bard Mythologies

- The Northern Antiquarian

- National Geographic article on vitrified forts

Map courtesy National Library of Scotland

Photos copyright © Colin Woolf

10 Comments

Finola

Wonderful stuff – but oh those legends are so full of blood and revenge. Superb illustrations!

Jo Woolf

I know, they don’t hold back! It’s distressing but I try to remember that they were (at least partly?!) superhuman / immortal!

Jo Woolf

Also, which has just occurred to me, Naoise had the sword of Manannan Mac Lir, which could cut down anything in its path!? So why didn’t he use it?

Bob Hay.

Whew Jo, I’m breathless after reading that epic and your research. These amazing lengthy old stories originated before the written word and not a few can be traced back to Europe (like fairy tales) but somehow made it to the British Isles. I think a lot of them survived in Ireland because they hadn’t come under the influence of the Romans. That’s a guess.

Great to see you back with pen in hand, figuratively speaking, as it seems ages since your last story.

Jo Woolf

Hi Bob, I always knew this one would grow arms and legs, haha! It could have been a lot longer as well – there is really so much to say (and still to learn) about Beregonium. I guess it’s quite possible that these legends (or versions of them) originated in Europe. When I was writing the Birds book I was astonished to find how old some of the legends are. Yes it’s been a while since the last post, but I’ve been busy writing in the meantime – I’ll have to write an update at some stage with news. Thanks for your comments – glad this was of interest! I loved the story myself and in a way I was quite glad we didn’t get to stand on the hillfort itself – easier to imagine it as the stuff of legend!

Bob Hay.

Hi Finola, if you think those legends are full of blood and revenge, you should read Colin M. MacDonald’s ‘History of Argyll’ where you’ll be provided with 1000 years of factual blood and revenge. Patricide, matricide, fratricide in big dods.

I don’t think any Clan Chief died peacefully in his bed.

Bob Hay

Maybe it looked like this. With all those towers😃

https://www.dreamstime.com/photos-images/disneyland-castle.html

Jo Woolf

Haha, maybe it did! 😀

davidoakesimages

A long read but well worth it…… they say that the truth is stranger than fiction, which always makes legends had to dismiss. (maybe a book with all your blog post would be good))

Jo Woolf

Thanks, David! Yes, that’s very true about legends. Hmm, that’s a good idea, which I’ll have to think about!