In search of MacMarquis’s chin

Patrick Hunter Gillies’ book, Netherlorn, Argyllshire and its Neighbourhood (1909) is a great source of half-forgotten information about the parishes and families of Argyll. Gillies was a doctor who lived on the island of Easdale in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so he obviously had access to a vast wealth of local history and lore.

Writing about the island of Seil, Gillies gives a brief summary of the church ministers in the parish of Kilbrandon from the 16th century onwards. The position seems to have been passed down through the MacLachlan family until the last incumbent, John MacLachlan, died in 1789. Gillies reveals that John was known locally as ‘Maighster Shon’, and he was buried below the crypt of the old parish church of Kilbrandon. He says: ‘A large flat slab of stone raised upon pillars, ornately carved with the Maclachlan coat of arms, and bearing a lengthy Latin inscription, marks the family burial-place.’

Then he adds a bit of extraordinary detail:

‘A curiously shaped fragment of basalt, resembling a human chin, rests upon the slab. It is known as ‘Smig mhic Mharcuis’ (the chin of MacMarquis). It is popularly believed that this stone, by some supernatural power, revolves upon its axis and points with the chin to a new-made grave, remaining in the same position until a fresh interment takes place. It is also said that should the ‘chin’ be removed from its place on the stone it will always return.’

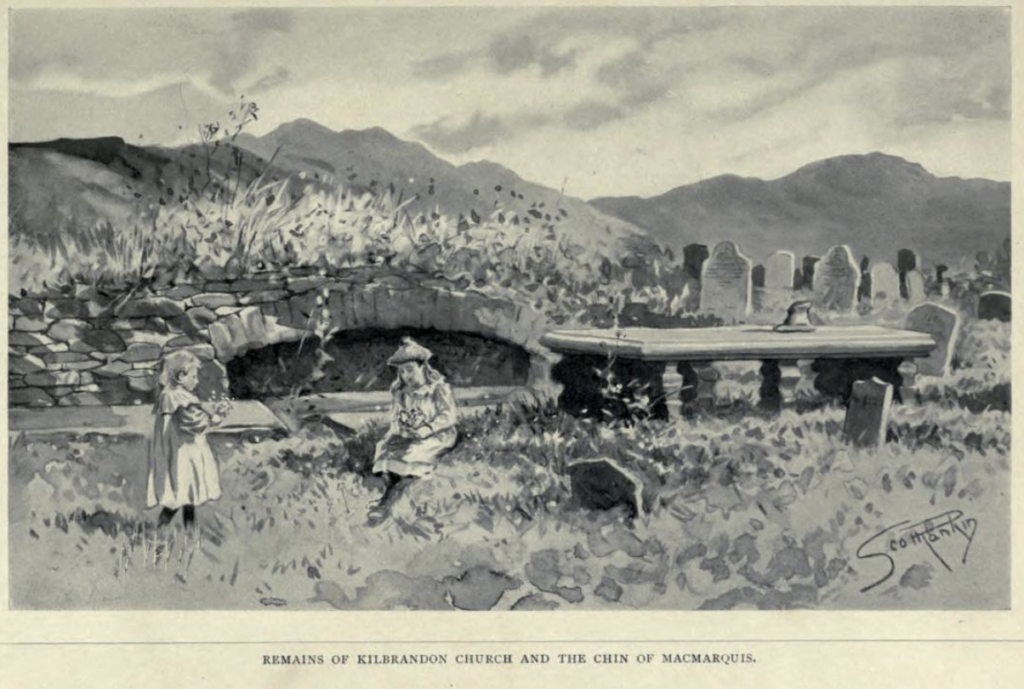

The idea of a chin that sits on a tombstone and revolves of its own accord has something very appealing about it. This remarkable artefact is even illustrated in Gillies’ book, sitting atop an old table tomb while two children play happily nearby.

Illustration by A Scott Rankin from Gillies’ Netherlorn, Argyllshire and its Neighbourhood (1909)

It was clear that a visit to the old churchyard of Kilbrandon was needed, just to see whether the chin was still there. Luckily, we had our friend Jarek visiting us, and he agreed to come along too. Last year, Jarek succeeded in finding Maclaine’s skull (or a version of it!) in Glengarrisdale, so who better to help us locate MacMarquis’s chin?

St Brendan and Kilbrandon on the Isle of Seil

Kilbrandon means ‘the cell of St Brendan’, and takes its name from St Brendan the Navigator, an Irish missionary-saint who was born around 484 AD. St Brendan went on a daring voyage in search of the legendary Isle of the Blessed, and according to medieval texts he had extraordinary adventures, beaching his little boat accidentally on the back of a sea monster and dodging flaming rocks that were hurled at him by the inhabitants of a strange island. He is credited with founding a monastic settlement on the Garvellachs, and he must have visited Seil because he gave his name to Kilbrandon. There is also a stone seat, called St Brendan’s Seat, high in the hills above Loch Seil.

St Brendan’s Seat

The island of Seil is accessed by a road bridge (the Bridge over the Atlantic) which spans a narrow neck of sea. On rising ground, close to the small settlement of Balvicar, a stone wall encircles quite a sizeable graveyard and it was here that the old parish church of Kilbrandon once stood. In Canmore’s records, the building is described as ‘medieval’, with a tradition that the original church was founded by St Brendan in about 545 AD. A number of grave slabs and monuments are listed, some dating back to the 14th or 15th century, and bearing the family names of Grant, MacDougall and Campbell as well as MacLachlan (or MacLauchlane).

The church is said to have been in ruins by the end of the 17th century, and all that survives of its structure is a portion of the north wall which incorporates an arched recess. It occupies the highest ground of the graveyard, and clustered around it are some grave slabs and one table tomb that definitely have an air of age about them.

Identifying the graves is another matter, however. The grave slab immediately under the recess (above) is carved with a skull and cross-bones, a traditional symbol representing ‘Memento Mori’ or a reminder of death. Above the skull is a winged angel, and below it, surrounded by a looping scroll, is a shield with an inscription at the base. According to Canmore, this includes the words ‘MR IOHANES MC/LAUCHLANE EVANGELII FIDELIS / PRAECO IN LORNIA INFERIORI AC / MELFORDA’ or ‘Mr John McLauchlane, faithful preacher of the gospel in Nether Lorn and Melford’ who died at the age of 78 on 3rd November 1685.

There was only one monument resembling Gillies’ description of a ‘large flat slab of stone raised upon pillars’. However, it was resting on two smaller square slabs, with just one carved pillar placed centrally beneath it. It was in a slightly different location from the one shown in Gillies’ book, being on the other side of the arched recess; Canmore mentions more than one table tomb, so it is possible that others have since collapsed. Unfortunately, it didn’t have anything sitting on it that looked like a chin, or indeed any kind of stone at all.

Above and below: a table tomb that may be the MacLachlans’. A carved pillar stands beneath it (just visible) but this doesn’t necessarily belong to this particular tomb.

Above: a recumbent slab, mossed over, bearing a coat of arms. Details here suggest a galley in a lower quarter, which features in the MacLachlan crest

Other notable monuments listed by Canmore include a grave slab dedicated to Margaret Campbell, wife of Robert Grant of Branchell, who died in Oban (apparently a township on Seil, not the present-day town further north) in 1681. Gillies has quite a bit to say about the unfortunate Robert Grant. He was the factor for Lord Neil Campbell of Ardmaddy, and on one fateful day he was sent to collect rents from Islay. On the voyage home, Grant’s boat was captured by a party of Macleans who had a feud with Campbell, and they bore Grant off to their castle at Duart on Mull where they imprisoned him.

Campbell asked a friend, MacDougall of Dunollie, to go to Duart Castle and negotiate Grant’s release. The Maclean chief, however, suspected that this might happen, and ordered Grant to be beheaded. When MacDougall arrived, he was given a courteous welcome and invited to dinner. Only after the meal was he allowed to broach the reason for his visit. On being asked if he would kindly release Robert Grant, Maclean coolly replied: ‘You may take his body, which is in the courtyard, but I will keep his head.’ MacDougall duly removed Grant’s body and had it buried in the churchyard of Kilbrandon.

An elder tree just outside the graveyard, loaded with berries

So, going back to the MacLachlans: Gillies tells us that their home, the ‘old mansion-house of Kilbride, has long since crumbled to ruins, but the garden remains…’ He adds that at one time the family was in possession of a prized collection of ancient Gaelic texts, known as the Kilbride manuscripts, which (he claims) may have been part of the original library of Iona. From what I can make out, they are now held by the National Library of Scotland.

But here are the questions I’d like answering: Who was MacMarquis? What did he have to do with the chin-shaped stone? Did he, perhaps, have a prominent chin in real life? It’s all a bit puzzling. Maybe MacMarquis was a nickname for one of the MacLachlans; or maybe he was a fictional character invented by the children who are depicted in Gillies’ book!

It’s interesting, however, that the chin is supposed to point towards the most recent burial. This reminds me of an old Highland belief, that the spirit of the last person to be buried in a graveyard has a duty to keep watch over all the other souls resting there until the next burial takes place, at which time the newcomer takes over the vigil. In his book, The Coffin Roads, which examines ancient funeral routes and customs in Scotland, Ian Bradley explains that: ‘This was regarded as an onerous responsibility and on occasions when two burials took place on the same day it was not unusual for each group of mourners to make great efforts, including resorting to physical force, to make sure that they reached the graveyard first so that their loved one was not left with the task of looking after the dead.’

But MacMarquis’s chin is said to point at every new burial, which suggests that he is reluctant to give up his role. Whoever he was, perhaps he was a generous, affable host and he is still looking after his friends in the afterlife.

Looking south-east

Looking north-east

Rowan berries glowing in the late summer sunshine

Where does all this leave us? Colin, Jarek and I made a careful inspection of this lovely old graveyard, but we failed to discover a chin-shaped rock. I don’t know whether to be glad, because it must be easily portable, and may be kept somewhere obscure and out of reach of acquisitive fingers… but on the other hand, it might have been removed or lost, in which case we can only hope that it exerts its supernatural homing power and returns to its rightful place. It has baffled other people too: here is a blog post on MacMarquis’s chin published in 2014 by the writer Marc Calhoun. He thought he’d found the chin, and then wasn’t so sure…

The old parish church of Kilbrandon has now been superseded by a more recent church, built in 1866 and also dedicated to St Brendan, which gazes down over sloping farmland towards Ballachuan hazel wood. It contains the most beautiful stained-glass windows by Douglas Strachan.

Reference and further reading:

Ian Bradley, The Coffin Roads (2022)

Patrick Hunter Gillies, Netherlorn, Argyllshire and its Neighbourhood (1909)

Canmore: Kilbrandon old church and graveyard

Scotland’s Churches Trust

Images copyright Jo Woolf

2 Comments

davidoakesimages

As always interesting, intriguing, legend and perhaps myth all wrapped up in another great post. As for chin bone, perhaps left undisturbed 🙂 Thanks again.

Jo Woolf

Thank you, David – I do love these obscure old stories, they’re sometimes stranger than fiction! Yes, totally agree with you there! 😀